Editor's Note

In recent years, the study of the South China Sea by Bill Hayton, a BBC journalist and associate Fellow with the Asia-Pacific Programme at Chatham House, has gained international popularity. Hayton is very good at using international media and international forums to disseminate his research. He is very often invited by media, international studies institutions, as well as major research platforms on the South China Sea to preach his version of “South China Sea Story”.

If Hayton's research on the South China Sea is objective, it would be helpful to promote peaceful resolution of the South China Sea disputes. Unfortunately, Hayton's research has adopted an extreme Eurocentric perspective, with a strong bias and lack of basic sympathy for the history of Asia, resulting in a very narrow and even diametrically different interpretation of the history of the South China Sea, deepening the rift between China and its neighboring countries. Mainly based on English newspapers in the first half of the twentieth century, Hayton’s research’s cognitive dimension is very narrow, and the interpretation is deeply fragmented, which even violates some basic historical common sense.

Moreover, Hayton does not have a comprehensive, comparative view of history. He likes to capture fragmented information for over-interpretation, and neglects the whole picture. With regard to territorial and maritime disputes, a relatively objective research conclusion can be reached only after weighing and comparing the evidences given by all the States concerned.

This article and the following two articles try to re-examine Hayton‘s research on the history of South China Sea, which is intended to reduce some prejudices and misunderstandings, and to promote a more balanced understanding of the history of the South China Sea.

Introduction

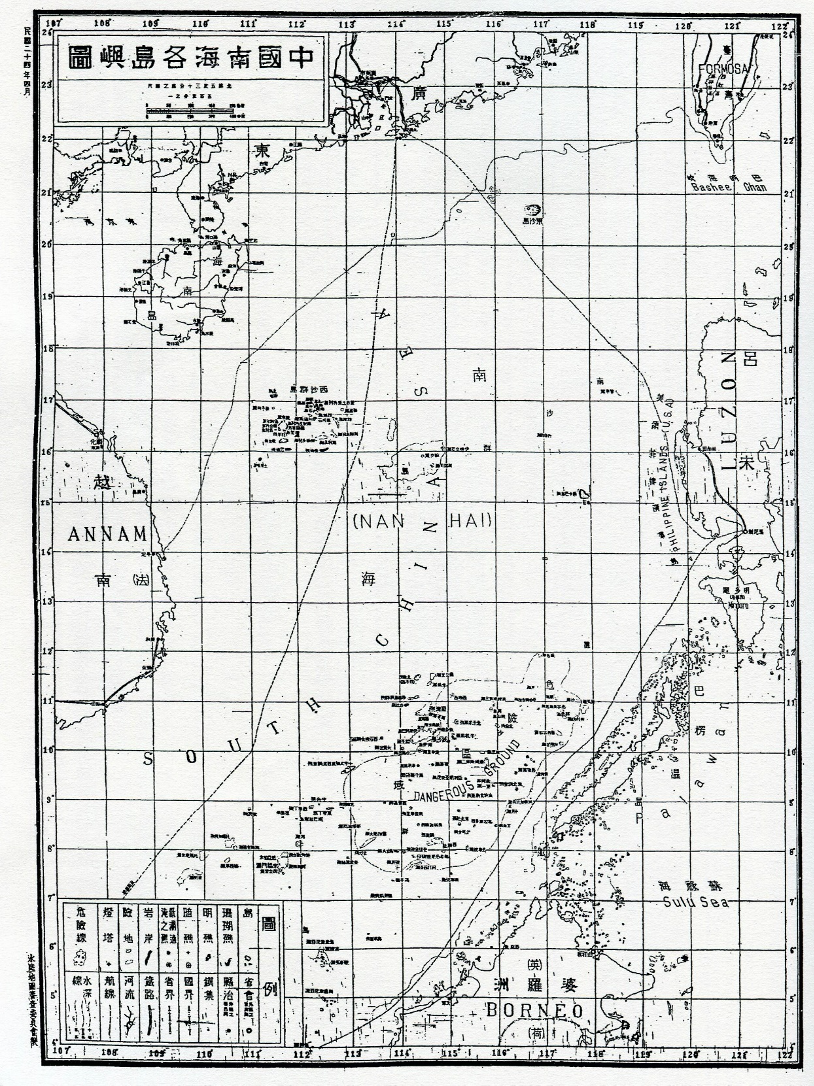

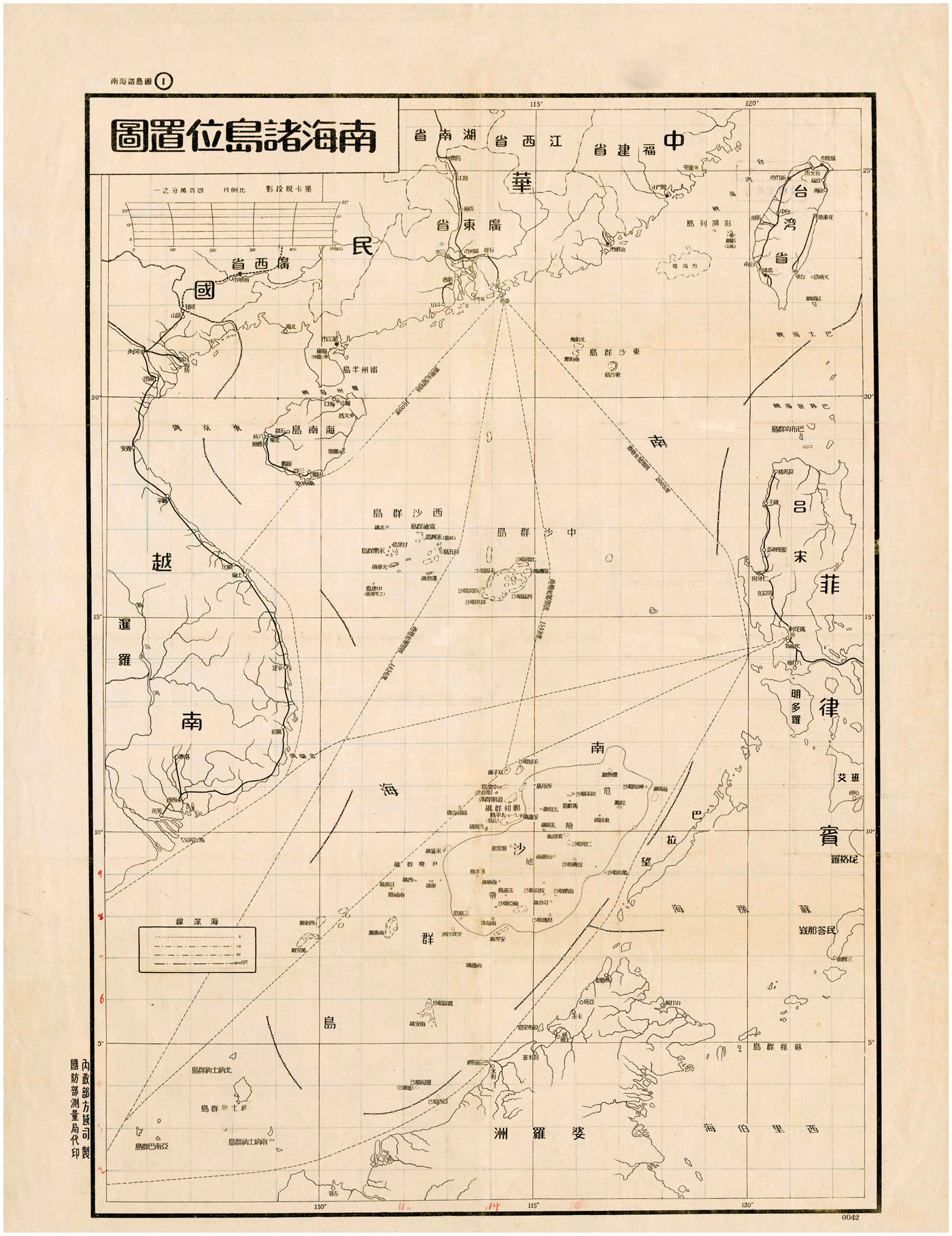

During the period Republic of China, there were mainly three formats of maps of the South China Sea. The first portrayed Pratas Island and the Paracel Islands only, leaving the other islands in the South China Sea unmarked. Examples include the New Geographic Map of the Republic of China compiled by Hu Jinjie and Cheng Fukai in 1914, [1] the New Chinese Situation Atlas developed by Tu Sicong in 1927, [2] and China’s Model Atlas edited by Chen Duo in 1933. [3] The second type included Pratas Island, the Paracel Islands, Macclesfield Bank and the Nine Islets in the Spratly Islands. One example is the Newly-Made Chinese Atlas (with indexes) by Chen Duo in 1934. [4] The third type included Pratas Island, the Paracel Islands, Macclesfield Bank and the Spratly Islands in their entirety, for example, the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China(《中国南海各岛屿图》) compiled by China’s Committee for the Examination for the Land and Sea Maps in 1935, [5] the New Atlas of China’s Construction by Bai Meichu in 1936, [6] the New Atlas of China’s Provinces and Cities by Su Jiarong in 1937, [7] the New Provincial Atlas of China edited by Ding Wenjiang, Weng Wenhao and Zeng Shiying in 1939, [8] the Location Map of the South China Sea Islands (《南海诸岛位置图》)produced by the Department of Territorial Administration under the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of China in 1948, [9] and the New Provincial Atlas of China (version 5 in the post-war era) edited by Ding Wenjiang, Weng Wenhao and Zeng Shiying in 1948. [10] Among them, the two officially released by the government of the Republic of China — the Location Map of the South China Sea Islands introduced in 1948 and the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China in 1935 are the most authoritative.

For years, academia has focused research on the Location Map of the South China Sea Islands, however, the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China has received little focus. Many even question the significance and value of the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China. According to Li Woteng, the connection between China and the islands in the South China Sea was very weak, let alone governance in real sense. The maps were only used for territory expansion in political terms. [11] The BBC journalist Bill Hayton suggests that: “the committee did not have the capacity to undertake its own surveys. Instead it undertook a table-top exercise, analyzing maps produced by others and forming a consensus about names and locations.” In the Table of Chinese and English Names for All of the Chinese Islands and Reefs in the South China Sea, the names in Chinese were mostly translated or transliterated from English, with many translation mistakes. [12] In the South China Sea Arbitration, the Philippines questioned: “On what basis does China purport to claim historic rights for an area over which it had so little involvement or connection that most of the features had no Chinese names?” [13] The Philippines further stated: “Contemporaneous archival research uncovered no historical basis for China’s claim to possess sovereignty over any island in the South China Sea, even the northern Paracel group, let alone historical rights in respect of the waters.” [14]

Map of the South China Sea Islands of China, 1935

The Map of the South China Sea Islands of China was the first official map produced by the Government of the Republic of China that included the Spratly Islands in China’s territory and clearly marked China’s territorial boundary in the South China Sea. How do we evaluate its significance from an international law perspective? [15] Considering relevant international legal practices, the weight of a map as legal evidence for a State’s territorial claims is mainly determined by five factors. First, whether the map can clearly show a State’s intention of sovereignty. Second, whether the map is accurate. Third, whether the map itself is neutral and objective. Fourth, whether maps of the country are consistent over time. Fifth, whether the map obtained recognition or acquiesce from the international community or States concerned. [16]

Within a legal context, how can we review the questions or mistakes in the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China objectively and comprehensively? This paper intends to review the significance of the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China from an international law perspective. The five factors above, which influence a map’s potency as evidence, are carefully considered, and further interpretations are made by following China’s transformation from the Qing Empire to a modern nation-state. The intention for this study is to inspire future in-depth studies and address certain questions concerning China’s map publication and cartography in this period.

1. The 1935 Map and China’s Sovereignty Intention

To show whether a map has probative force relating to a State’s territorial claims, the most critical issue is to clarify whether the map reflects the will of the State, particularly its territorial intent. In 1986, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) pointed out in the Frontier Dispute (Burkina Faso/Republic of Mali) that “maps can still have no greater legal value than that of corroborative evidence…except when the maps are in the category of a physical expression of the will of the State.” [17] Then in 2002, the ICJ further noted in the case concerning the Sovereignty over Pulau Ligitan and Pulau Sipadan (Indonesia/Malaysia) that, “…in some cases maps may acquire such legal force [establishing territorial rights], but where this is so the legal force does not arise solely from their intrinsic merits: it is because such maps fall into the category of physical expressions of the will of the State or States concerned. This is the case, for example, when maps are annexed to an official text of which they form an integral part.” [18] In the Island of Palmas Case (Netherlands v. U.S.A.), Judge Max Huber stated that, “…only with the greatest caution can account be taken of maps in deciding a question of sovereignty … anyhow, a map affords only an indication – and that a very indirect one – and, except when annexed to a legal instrument, has not the value of such an instrument, involving recognition or abandonment of rights.” [19] Therefore, whether a map can reflect a country’s sovereignty intention forms the basis of its probative value under international law.

Bill Hayton has contended that:

"It is not clear from the evidence available that the committee was actually asserting a territorial claim to the Spratly, even at this point – 1935. In April 1935, the second volume of the Committee’s journal included a map with an ambiguous title, 中國南海各島嶼圖, which may be translated as ‘Map of China’s Islands in the South Sea’ but also ‘Map of Islands in the South China Sea.’ It showed the locations of the islands with their new Chinese names. There was no boundary line marked on the map and no indication about which features the committee considered to be Chinese and which were not. It could be that they considered all the named islets, rocks, reefs, and submerged banks to be Chinese, but the map makes no distinction between their names and those of places that we can assume the committee did not regard as Chinese, such as Manila. [20]"

It should be pointed out that the Land and Water Maps Review Committee, which was established in June 7, 1933, was an official body composed of representatives from the Ministry of the Navy, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Education, Mongolian and Tibetan Affairs Commission and other institutions under the initiation of the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of China, with a mission to review and determine the territories of the Republic of China. As was stated, the Committee worked “…with a focus on compiling standard maps and reviewing maps of all kinds” to prevent “the incorrect relay of erroneous information due to intentional and unintentional reasons.” [21] Within its mandate, in the identification of territorial boundaries, the Committee undoubtedly represented China’s will. In this sense, the reviewed and approved Table of Chinese and English Names for All of the Chinese Islands and Reefs in the South China Sea and the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China is an official and authoritative manifestation of China’s State will.

The above two documents specified China’s territorial scope in the South China Sea, encompassing Dongsha Island, the Xisha Islands, the Nansha Islands (now the Zhongsha Islands), and the Tuansha Islands (now the Nansha Islands). Furthermore, the title Map of the South China Sea Islands of China in itself spoke for the intention to clarify China’s sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea, providing a strong sense of political and sovereign intent. As to the ambiguity issue proposed by Bill Hayton, if the title were to be interpreted from the Chinese language, there would be no ambiguity at all; rather, it clearly states China’s claim of sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea. Meanwhile, on March 22, 1935, the resolution of the 29th meeting of the Committee also clearly stated that Dongsha Island, the Xisha Islands, the Nansha Islands and the Tuansha Islands must be included when sketching maps of jurisdictions and territories. [22]

Additionally, the historical background of the map’s production should also be discussed. The Map of the South China Sea Islands of China was made under the situation which China faced with the combined disruptions of internal revolution and external invasion. At that time, France and Japan were meddling in the normal peacetime status of the islands in the South China Sea. In those days, civil society strongly criticized the Government of the Republic of China for being unresponsive and ineffective in its response. Under these circumstances, the Government of the Republic of China produced this map and others, in a bid to clarify China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea islands and thus respond to the unlawful occupation of islands and reefs by these foreign powers. Bill Hayton acclaimed that the absence of a boundary line made it impossible to distinguish Chinese maritime features from those of neighboring countries. However, with additional observation, it can be observed that the mapmakers had clearly noted “Philippines Islands(U.S.A.)” “美领菲律宾群岛”on the Philippine Archipelago, “the British Commonwealth”(“英” ) on the Northern part of Borneo, “the Netherlands” (“荷”) on the Southern part of Borneo, as well as “France”(“法”) signifying Vietnamese land in French Indo-China. There was no distinct marking of this type for the South China Sea islands, they were marked in the same way China had dealt with the Hainan Island and the areas along the coastline of Guangdong — all default territories of China, thus being consistent with the title “Map of the South China Sea Islands of China”.

In short, taking into full account the compiling body, the name of the map, the historical background of mapmaking, it would not be difficult to determine that the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China expressed the Chinese Government’s intentions of sovereignty for the South China Sea islands at that time.

2. Accuracy of the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China

The technical accuracy of a map is an important consideration for judging the probative force of it as evidence. In the frontier dispute case between Burkina Faso and the Republic of Mali, the Judge of the ICJ observed that “the actual weight to be attributed to maps as evidence depends on a range of considerations, some of which relate to the technical reliability of maps. … technical reliability had increased considerably owing to the progress achieved by aerial and satellite photography since the 1950s.” [23] In the Island of Palmas Case (or Miangas), Judge Max Huber even more clearly stated that, “the first condition required of maps that are to serve as evidence on points of law is their geographical accuracy.” [24]

In regard to the accuracy of the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China, Bill Hayton has also raised this question, “the Committee did not have the capacity to undertake its own surveys. Instead it undertook a table-top exercise, analyzing maps produced by others and forming a consensus about names and locations.” In the Table of Chinese and English Names for All of the Chinese Islands and Reefs in the South China Sea, “what is remarkable about these names is that all were translations or transliterations of the names marked on British maps… I suspect that this map (a 1918 map entitled Asiatic Archipelago) also guided the committee’s choices about which features to give Chinese names to. There are some errors in the committee’s list. The committee also made mistakes in its translations.” [25]

Generally speaking, the more accuracy a map that is used to identify territorial boundaries has, the more weight will be attributed to it as an evidence. Nevertheless, we should bear in mind that the main purpose for a political map is to identify a state’s position and its territorial claims. In particular, for areas that are not yet delimited and thus subject to dispute, the accuracy of the map should be evaluated according to its purpose and function. If a map can basically reflect a country’s territorial claims in clarity, it should be deemed as accurate enough. According to the award of Beagle Channel Arbitration (Argentina v. Chile), the ICJ pointed out that “the importance of a map might not lie in the map itself, which theoretically might even be inaccurate, but in the attitude towards it manifested – or action in respect of it taken – by the Party concerned or its official representatives.” [26]

It is true that the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China borrowed some information from British maps. But it is noteworthy that at a time when aerial photography and satellite remote sensing technologies were underdeveloped, it was a rather common practice to complement each other's advantages instead of measuring every feature on site. The accuracy of a map should be assessed against mapping techniques at that time rather than modern technical standards and technological conditions. [27] Maps are sketched to reflect a State’s position and territorial claims. Any map that serves this purpose should be deemed accurate as it clearly portrays the intent of the state that publishes it. The Map of the South China Sea Islands of China can clearly reflect the Chinese Government’s position and territorial claims of the islands in the South China Sea, which fully speaks for its sufficient accuracy.

3. The Neutrality and Objectivity of the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China

The significance of a map under international law also depends on its producer’s neutrality, objectivity and authority. Generally speaking, maps produced by independent mapping experts have greater weight as an evidence. On the contrary, those produced under the direction of a single party have less significance. In the case of Frontier Dispute (Burkina Faso/Republic of Mali), the ICJ pointed out that “other considerations which determine the weight of maps as evidence relate to the neutrality of their sources towards the dispute in question and the parties to that dispute.” [28] In the case concerning Kasikili/Sedudu Island (Botswana/Namibia), Judge Oda also stated that “a map produced by a relevant government body may sometimes indicate the government’s position concerning the territoriality or sovereignty of a particular area or island. However, that fact alone is not determinative of the legal status of the area or island in question. The boundary line on such maps may be interpreted as representing the maximum claim of the country concerned but does not necessarily justify that claim.” [29]

The Map of the South China Sea Islands of China produced in 1935 was a direct response to the occupation and annexation of the islands in the South China Sea by France and Japan during a period of conflict within Mainland China. From the sovereign intention perspective, the map asserted China’s state will and constituted a countermeasure against France and Japan’s annexation activities. In the meantime, the map confirmed the fact that the Chinese fishermen had been utilizing the islands in the South China Sea for human habitation and economic life for several thousand years. [30] Generally speaking, maps are always produced by specific countries. Therefore, it is normal for a country, in particular a party to a territorial dispute, to produce maps to reflect its sovereign intention. International judicial practices have determined that a map should not be disqualified as evidence of fact just because it is produced by one party to the dispute, but be assessed in combination with all other factors, including all other relevant evidence. [31]

4. The Consistency of the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China

The inconsistency of maps released at different times is likely to affect their reliability, and at the same time go against the doctrine of estoppel. For example, in the case concerning Kasikili/Sedudu Island (Botswana/Namibia), the ICJ stated that“in the light of the uncertainty and inconsistency of the cartographic material submitted to it, the Court considers itself unable to draw conclusions from the map evidence produced in this case”[32]

A map should be consistent, otherwise the true intention of the State cannot be identified from it. Therefore, to prove a state’s consistency in its territorial claims, international judicial institutions usually require that maps provided by the parties concerned as evidence should be consistent with each other. [33] In the meanwhile, considering the technical restrictions map creation has undergone over time, including mapping standards and conditions as well as scientific technologies, the requirement for map consistency is not absolute, but basic consistency should be maintained. [34]

Bill Hayton has stated that China gradually expanded its claims in the South China Sea southwards since early 1900s and finally established its maritime geobody. [35] According to Li Woteng, “Before 1908, the islands in the South China Sea can be found in no Chinese map. Between 1909 and 1917, the Paracel Islands and Pratas Islands were gradually included in Chinese maps. Between 1917 and 1934, the Paracel Islands and Pratas Island were included on Chinese maps as China’s territories, but as shown in the maps, the Macclesfield Bank and the Spratly Islands were still not considered as being part of China. Since 1935, the Macclesfield Bank and the Spratly Islands started to be included into all Chinese maps and the Scarborough Shoal was sketched out in most of the maps. After 1947, the government of the Republic of China defined the boundary around the South China Sea with the eleven-dash line. Since then, the South China Sea has been basically the same on Chinese maps (except that the eleven-dash line was replaced by the nine-dash line after the founding of the People’s Republic of China).” [36] Here, Li Woteng blurred the distinction between official and private maps. Private maps have no legal effect in international law unless verified by the state’s authorities. [37] The Map of the South China Sea Islands of China published in April 1935 was the “first official map of the South China Sea publicly released by the Government of the Republic of China.” [38] The publication aimed to regulate and rectify the confusing and disorderly condition of the map market in China at that time. In this sense, the differences contained in the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China from the previous private maps has no adverse impact on its legal effect.

Since the publication of the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China in 1935 claimed Pratas Island, the Paracel Islands, Macclesfield Bank and the Spratly Islands as Chinese territories, although the national regime has shifted, the Chinese Government has been consistent regarding its claim to these islands. Also, as for Li Woteng and others’ accusation of the Government of the Republic of China to be “expanding boundaries on the maps”, it holds no water at all. China was in a weak state under the continual armed threat of the colonial powers. Therefore, it would be a clearly absurdity for China to risk “expanding territories”. [39] At a time when France and Japan nibbled or devoured islands in the South China Sea, and China was in a state of conflict, the Committee mapped and released the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China was only to defend its sovereign territory. Essentially, the map aimed at safeguarding China’s legal rights by asserting the extent of the country’s territories in the South China Sea.

5. Stakeholders’ Recognition or Acquiesce in the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China

Whether a map is recognized or acquiesced by stakeholder countries, and whether it reflects the international community’s overlapping consensus is a key factor to assessing its legal implication. The Eritrea-Ethiopia Boundary Commission pointed out correctly that “a map per se may have little legal weight: but if the map is cartographically satisfactory in relevant respects, it may, as the material basis for, e.g., acquiescent behavior, be of great legal significance.” [40] It further stated that “a map produced by an official government agency of a party, on a scale sufficient to enable its portrayal of the disputed boundary area to be identifiable, which is generally available for purchase or examination, whether in the country of origin or elsewhere, and acted upon, or not reacted to, by the adversely affected party, can be expected to have significant legal consequences.” [41] The 1935 Map of the South China Sea Islands of China itself was an outcome of China’s reaction to France and Japan’s annexation. There was no evidence proving that the map had been acknowledged or acquiesced by Japan, or France at that time. However, both Japan and France renounced potential rights to the islands and reefs in the South China Sea. It should be noted, when the Location Map of the South China Sea Islands was published in 1948 as a continuance to the 1935 map, the International Community, in particular the neighboring stakeholder countries or their colonial masters, filed no objection for a long period. [42] Yehuda Blum observed that:

"Recent instances of protests lodged against ‘map claims’ seem to indicate that States do, in fact, ‘keep a vigilant watch over the maps published by the civilized nations’…On the whole, it seems to emerge that States will be imputed with knowledge of each other’s domestic legislative activities and other acts done under their authority, and that the plea of ignorance will be accepted only in the most exceptional circumstances. States desirous of reserving their rights will therefore be well advised to follow with a substantial amount of self-interested awareness the official acts of other States and to raise an objection to them—through the legitimate means recognized by international law—should they feel that their rights have been affected, or are likely to be affected, by such acts." [43]

In the case concerning the Temple of Preah Vihear (Cambodia v. Thailand), the ICJ gave a clear interpretation of the unfavorable consequences that may result from a State’s silence and lack of reaction, by pointing out: “It is clear that the circumstances were such as called for some reaction, within a reasonable period, on the part of the Siamese authorities, if they wished to disagree with the map or had any serious question to raise in regard to it. They did not do so, either then or for many years, and thereby must be held to have acquiesced. Qzri tacet consentire videtur si loqui debuisset ac potuisset.” [44] Accordingly, we may presume that the stakeholder countries have to a certain extent acknowledged or acquiesced in the Map of the South China Sea Islands of China.

Location Map of the South China Sea Islands,1948

Conclusion

China has suffered great challenges and humiliation, inflicted by colonial powers since the outbreak of the Opium Wars in the mid-19th century. Since 1864, China has tried to learn and use the concept of Western International Law to defend its territorial integrity. As Joseph Levenson put it:

“The history of modern China is a journey from Tian Xia(all under heaven/天下)to a nation-state.” [45] “Tian Xia is a civilization order concept based on the sharing of Chinese culture and ethical order.” [46]

Under the order of Tian Xia system, countries are not separated by concrete boundaries but united by culture and moral appeal. The Western vocabulary of sovereignty, nation-state and boundary is ill-suited for the traditional Chinese worldview.

The Map of the South China Sea Islands of China published in 1935 was produced in the process of State transformation. It failed to fully reflect the history of the Chinese people, in particular, the Chinese fishermen exploring, naming, using and managing the islands of South China Sea, in acts that are described today as forming the foundation of an economic and human life. It was also flawed in naming islands and providing geographic information in detail suitable for navigational purposes. Nevertheless, the 1935 map was the first of its kind that the Government of the Republic of China officially published to define China’s territorial scope in the South China Sea. It fully and clearly reflected China’s sovereignty intent and territorial claims over the islands in the South China Sea. Even from the perspective of modern International Law, China's claim on the islands and reefs in the South China Sea is much earlier than that of its neighboring countries. In addition, considering the development of mapping technologies at that time, the 1935 map was accurate enough when compared to other territorial maps. The sovereignty claims on the islands in the South China Sea portrayed by the 1935 map was inherited by other official maps such as the Location Map of South China Sea Islands, which represents China’s consistent and continuous claims over the islands in the South China Sea and also the long-term acquiescence of neighboring countries.

The 1935 map has not only significant value in proving China’s territorial sovereignty of the islands in the South China Sea, but also profound meaning as a facilitator of China’s transition into a modern nation-state, defining its geographical boundaries and safeguarding China’s maritime rights and interests today.