Since the end of the Cold War, especially over the past two decades, the awareness of the importance of crisis management between China and the United States has been greatly strengthened, the mechanisms of exchange, communication and dialogue have been established, and the rules of military interaction are also being explored. However, amid the backdrop of intensified China-US military competition and increased security risks, the efforts for crisis management are inadequate. So far, China-US maritime crisis management mechanisms mainly include high-level interactions, communication and exchange mechanisms, and military rules of conduct.

1.High-Level Interactions

The Presidents of China and the United States maintain frequent interactions through meetings, a hotline, special representatives and telegrams, with maritime crisis management as a major topic. The direct face-to-face meetings between the heads of state of the two countries play a crucial role in stabilizing bilateral relations, and almost all the major progress of crisis management between the two countries and the two militaries were made during the summit meetings. The meetings, including state visits and informal meetings on multilateral occasions, are the bellwether for the direction of the bilateral relationship. In 1997, China and the United States agreed to set up a head of-state hotline, and in 1998, officially established a direct telephone communication line for the two presidents. The two heads of state usually exchange greetings on important days or exchange views on major events. Special representatives of the president are also an important and flexible way for the two heads of state to advance important agendas or transfer signals. The telegram is a convenient and rapid communication document to express congratulations, thanks or condolences to the other party. However, head-of-state interaction is highly strategic, concerning almost all major issues of the two countries’ relationship, and alleviating maritime competition is not always on the core agenda. With the increase of competition and friction in other areas of the relationship, maritime crisis management will be increasingly overshadowed by other issues like trade and ideology.

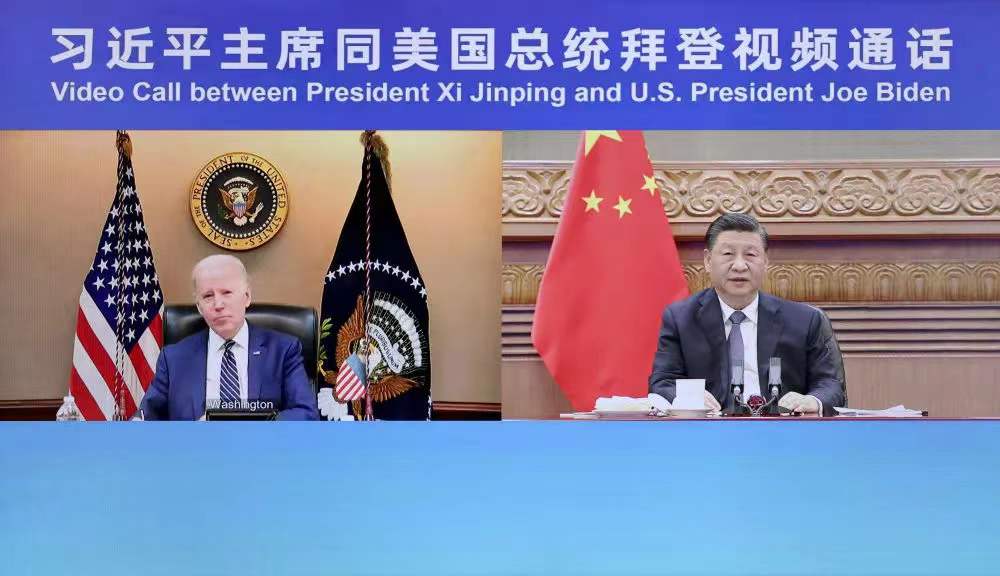

The Presidents of China and the US had a video call on March 18, 2022.

Aside from the interactions between the two leaders, the ministers of defense, the chiefs of staff of the Joint Staff, service commanders, theater commanders and other senior officials from both sides maintain mutual visits and exchanges. However, in recent years, the interaction has weakened significantly, influenced by the relationship between the two countries and militaries and the COVID-19 pandemic. In multilateral occasions, officials such as the ministers of defense of the two sides usually hold ceremonial or formal meetings, which may lack substantive content.

2.Communication and Exchange Mechanisms

2.1 The Defense Consultative Talks (DCT)

The Defense Consultative Talks were first established in 1997, with the level of viceministerial for its delegations. The DCT is meant to exchange views on major defense issues. By October 2014, it had been held 15 times, but has no further activity after that.

2.2 The Joint Strategic Dialogue Mechanism (JSDM)

China and the United States signed an agreement on the Joint Strategic Dialogue Mechanism in Beijing in August 2017. There has been only one formal dialogue reported publicly. On January 11, 2018, General Joseph Dunford, the then chairman of the United States’ Joint Chiefs of Staff, held a video conference to discuss bilateral cooperation with General Li Zuocheng, Chief of Staff of the PLA Joint Staff Department. Besides, on October 30, 2020, and January 8, 2021, General Mark Milley, the chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, twice called Li Zuocheng, to assure that the two countries would not suddenly go to war.

2.3 The Defense Policy Coordination Talks (DPCT)

The Defense Policy Coordination Talks were established in 2005 and are the platform for both sides to exchange policy views regarding their militaries. It is mainly to implement the decisions reached by the two presidents, the leaders of the defense departments, and to communicate and coordinate the agenda of exchanges and dialogues. Currently, the DPCT is the most active and important formal channel between two militaries and runs every year. On September 28 and 29, 2021, the 16th U.S.-China DPCT was co-hosted virtually by Dr. Michael Chase, U.S. Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for China, and Major General Huang Xueping, Deputy Director of the Chinese People's Liberation Army Office for International Military Cooperation.

2.4 The Military Maritime Consultative Agreement (MMCA)

Signed in 1998, the Military Maritime Consultative Agreement was the first military agreement between the U.S. and China, and includes an annual conference, plenary sessions and working group meetings. The rank of the annual conference is major general or lieutenant general. The MMCA is meant to communicate and manage differences and risks at sea and in the air of the two militaries. The MMCA is currently the most crucial China-US maritime security communication and dialogue channel, and both sides are willing to continue to negotiate. Except for 2020, it works smoothly generally. On December 14-16, 2021, military representatives from U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, U.S. Pacific Fleet, and U.S. Pacific Air Forces met virtually with the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy and Air Force representatives for the MMCA Working Group and Flag Officer annual session. However, the challenge is rapidly expanding. On the one hand, the contradiction in agenda setting is becoming increasingly acute. While China emphasizes operational safety as well as sovereignty, national security and other strategic issues, the US mainly focuses on operational safety. The friction existed ever since the establishment of the mechanism, but in recent years, the willingness to compromise and mutual tolerance on agenda setting is reduced. On the other hand, both sides are dissatisfied with the effect of communication. The mechanism is limited to opinion exchanging and sharing of concerns, but is not problem-solving nor binding.

2.5 The Defense Telephone Link (DTL)

The Defense Telephone Link, as the essential channel of exchanging hot issues between the ministries of defense, was established in November 2007 between the two defense departments, and both sides’ ministers held the first conversation in April 2008. The frequency of the Defense Telephone Link is not fixed, dependent on the development of some particular situation and the needs of work. The channel is intended for exchanging views and maintaining communication, representing form over substance. However, as the military competition between China and the United States intensifies, the DTL will be increasingly vital and indispensable.

There are also some suspended mechanisms including the Strategic Security Dialogue (SSD), the Asia-Pacific Security Dialogue (APSD), and the Diplomatic and Security Dialogue (DSD).

3.Military Rules of Conduct

3.1 The International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea 1972 (COLREGS)

Since the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea 1972, formulated by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), came into force on July 15, 1977, it has served as a globally recognized maritime traffic standard. Both China and the US are member states. The rule is basically adequate for handling most unplanned encounters.

3.2 The Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES)

According to the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea adopted in 2014, in the event of unplanned encounters by naval vessels or aircraft of different countries, necessary safety measures and means should be taken to minimize mutual interference and uncertainty and to facilitate communications. CUES defines the legal status, rights, and obligations of naval vessels and aircraft and provides maritime safety procedures, communications procedures, signals vocabulary, and basic maneuvering instructions for unplanned encounters at sea. So far, both Chinese and US forces have generally abided by CUES, but certain disputes remain in their scope of application. China insists that CUES does not apply to territorial waters, while the US holds that it does. Furthermore, the US expects to extend CUES to coast guards. From the perspective of China, the capabilities and operational scopes of each side’s coast guard are mismatched. The US Coast Guard is deployed globally, whereas the China Coast Guard mainly operates in China’s surrounding sea areas.

3.3 Two Memoranda

In 2014, China and the US signed the Memorandum of Understanding on Notification of Major Military Activities and Confidence-Building Measures Mechanism and the Memorandum of Understanding Regarding the Rules of Behavior for Safety of Air and Maritime Encounters. In 2015, the two countries agreed on the annexes on the military crisis notification mechanism and the rules of behavior for safety in air-to-air encounters. So far, these are the most concrete institutionalized arrangements between the two militaries. Nevertheless, the operation of these rules requires a positive political atmosphere and overall relationship. Generally, these two Memoranda are not mandatory and provide few detailed rules to be implemented in operations. Therefore, they cannot carry out substantive effects on alleviating the risks and frictions of encounters between the two militaries.

Related research

Hu Bo, "Systemic obstacles and possible solutions to crisis management between China and the US", China International Strategy Review, volume 3, pages 261–277 (2021).