Professional Deficiencies May Lead to Strategic Misunderstanding

Recently, the attention of the international community has been led to China’s potential establishment of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the South China Sea. Several media in Hong Kong and Taiwan region, as well as some Western media, accused China’s ADIZ of being “unique” and constituting a “threat to its maritime neighbors”. In early May, 2020, Taiwanese media reported that the defense and security departments of Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) administration were concerned of a potential South China Sea ADIZ[1]. In late May, an article of the South China Morning Post reported that “according to a source from the People’s Liberation Army”, Beijing has been making plans for an ADIZ in the South China Sea[2]. Also, well-known media in the West, including the National Interest[3] and the Economist[4], provided their “in-depth” and “professional” analyses. Days ago, General Charles Q. Brown, Jr., the incumbent U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff, expressed his concern for a potential Chinese South China Sea ADIZ, saying that such move would have a negative impact on “a free and open Indo-Pacific.”[5]

Mud sticks. In a short period of time, the clamor of media has grown louder. Despite China’s Foreign Ministry Spokesperson’s clarification[6], foreign stakeholders still seemed to be unsatisfied. Undoubtedly, China has the right to set up an ADIZ in the South China Sea and is not obliged to report to anyone about the time and specifics of such a plan. The key is that there is no evidence at all that the Chinese government intends to announce a South China Sea ADIZ any time soon.

As a matter of fact, this is not the first time that Western media make ungrounded assumption about a potential Chinese South China Sea ADIZ. Ever since China established the East China Sea ADIZ in November 2013, a potential South China Sea ADIZ has frequently made the headlines. Despite the media’s enthusiasm, it is hard to find any truly in-depth research by the academia regarding the relevant international laws or the differences among the practices of countries that have established their own ADIZs. Meanwhile, some Western think tanks have been taking their advantage of the interpretation of so-called “international rules” to make up “threatening” theories about China’s establishment of an ADIZ in its own coastal area. Their goals are more than obvious: to drive a wedge between China and Japan, South Korea and ASEAN countries, so as to impede cooperation between China and such countries. What is disguised behind is their motives to cause diplomatic tensions and accidental clashes between China and states concerned. This article focuses on basic facts from an international law perspective and points out what has been missing and wrong in the accusations of some Western think tanks and media reports due to technical deficiencies.

First of all, what is an ADIZ? From the perspective of relevant international laws, there has been a gap as regard to the establishment of an ADIZ and its related operating rules. The 1944 Convention on International Civil Aviation (also known as the Chicago Convention) and the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea are all silent on the application rules of ADIZs. It was not until 2000 that the definition for ADIZ and relevant “Recommended Practices” were introduced into Annex 15 to the Chicago Convention (which has no legally binding force).[7] According to Annex 15, an ADIZ is defined as “special designated airspace of defined dimensions within which aircrafts are required to comply with special identification and/or reporting procedures additional to those related to the provision of air traffic services (ATS).”[8] As the “pioneer” of establishing ADIZs, the U.S.’s practice in this area has played a significant role in the forming of relevant rules. Its definition of ADIZ[9] stipulated in 14 CFR Part 99 has been widely adopted by international law scholars. For example, according to the Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, “an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) is a defined area of airspace within which civil aircrafts are required to identify themselves. These zones are established above the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) or high seas adjacent to the coast, and over the territorial sea, internal waters, and land territory.”[10]

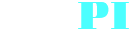

Second, does a country’s ADIZ have to be related to its territorial sovereignty and maritime boundary? It should be pointed out that the establishment of an ADIZ does not entitle the declaring state any territorial sovereignty, sovereign rights or jurisdiction over the areas covered. However, some reports assert that there are some connections between the outer boundary of China’s East China Sea ADIZ and “its claimed continental shelf”. The Economist even argued that an ADIZ can be used to show authority. The example it used as an argument is the dispute over ADIZ delimitation between Japan and Taiwan authorities in 2010. According to the Economist, Japan’s expansion of its ADIZ was to cover the Yonaguni, a Japanese-held island that was “claimed” by Taiwan authorities and included in Taiwanese ADIZ. In fact, Taiwan authorities never questioned Japan’s sovereignty over the Yonaguni Island. Moreover, Taiwan authorities’ ADIZ only covered around two-thirds of the Western of the island, not the whole. Some experts alleged that China’s “vague” or “ambiguous” claim in the South China Sea is a drawback for marking the coverage of the South China Sea ADIZ.[11] Such judgments exposed their inexperience concerning the theory and practice of ADIZ. It should be emphasized that the coverage of a country’s ADIZs has no direct relation to its claims regarding territorial sovereignty or maritime boundary. Therefore, even if China really planned to establish a South China Sea ADIZ, its scope might cover all islands and reefs in the South China Sea, or leave some islands out (for example, the U.S.’s Hawaiian ADIZ used to cover the territorial airspace over a majority of islands in the area, and subsequently excluded some islands. See Figure 1). Therefore, whether or where to establish an ADIZ in the South China Sea, is at the sole discretion of China.

Figure 1: The appendix in the U.S. Federal Register (June 17, 1961)

regarding the proposed adjustment of Hawaiian ADIZ

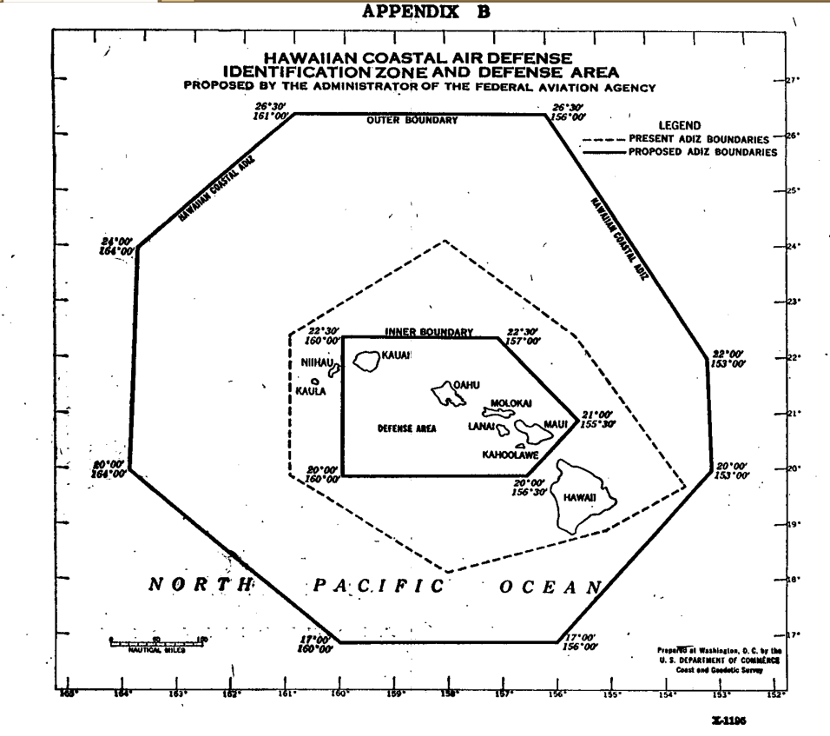

Even if China were to drop its claims over some islands currently occupied illegally by foreign states, it could still include those islands in its South China Sea ADIZ. There are several international precedents for governments establishing an ADIZ over indisputable territory of another state. For instance, South Korea’s ADIZ (see Figure 2) covers the disputed “Dokdo” Island (known as “Takeshima” by Japan), as well as a large portion of North Korea’s territory south of 39°00’N.

Figure 2: South Korea’s ADIZ

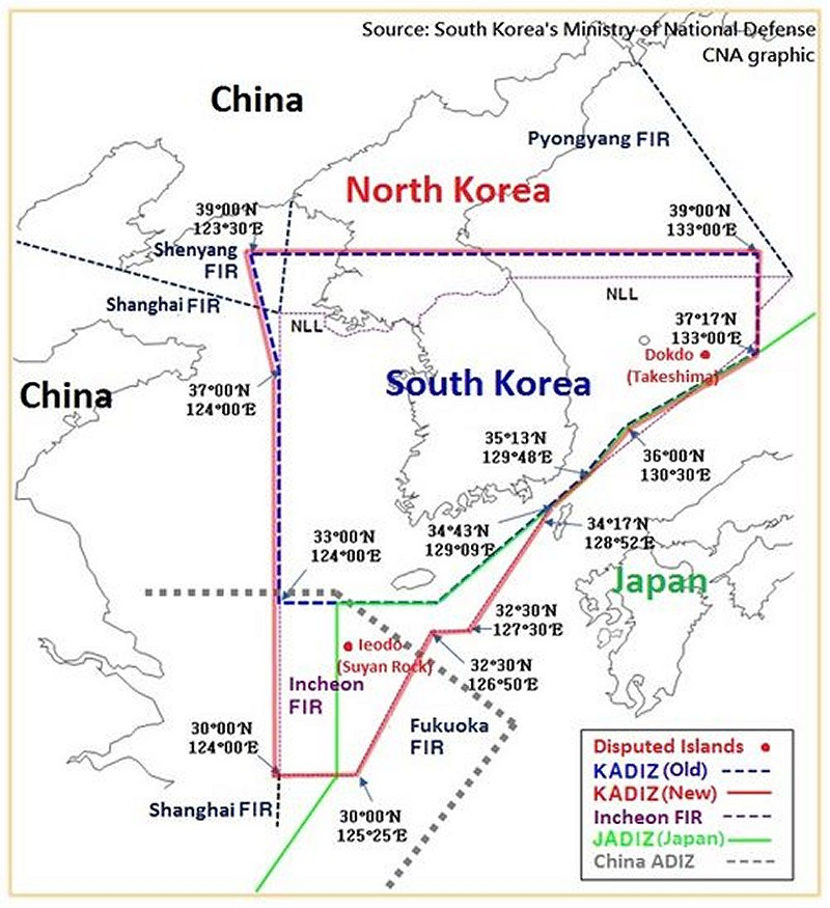

To emphasize that China’s East China Sea ADIZ is different from others (i.e. enclosing disputed territory), Jen Psaki, then the spokesperson of the U.S. Department of State complimented that the expanded South Korean ADIZ “does not encompass territory administered by another country”[12]. Obviously, Jen Psaki was turning a blind eye to basic facts. In addition, as the first country to establish ADIZs, the U.S. has been including other countries’ territory into its ADIZs since 1950. The Pacific Coastal ADIZ used to cover Guadalupe Island of Mexico from 1950 to 1988; and to date, the Contiguous U.S. ADIZ still partially covers the territorial airspace of Bahamas, such as the Dog Rocks (see Figure 3). As regards the inclusion of another country’s territory into U.S. ADIZs, no criticism has been heard.

Figure 3: U.S. ADIZs in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (1962)

As shown in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (1962), both the Guadalupe Island of Mexico (29°01′24″N, 118°16′21″W; roughly marked as green point) and the Dog Rocks of Bahamas (24°03′27″N, 79°52′14″W; roughly marked as red point) were included in U.S. ADIZs respectively.

Third, is the establishment of an ADIZ related to air defense capabilities and military air patrols? It is true that China has enhanced its maritime awareness capability in the South China Sea in recent years, as some Western critics have noticed. However, it is incorrect to take this as an accusation against China for planning to establish a South China Sea ADIZ because there is no causal connection at all. Most countries have never established any ADIZ, which does not necessarily mean they never internally designated any air defense early warning area (within which the fighter jets may be scrambled to identify, escort or intercept unidentified aircraft entering such area). For example, the Soviet Union and later the Russian Federation have never publicly announced any ADIZ, which does not mean the Russians have placed no importance on air defense or they have been weak at air defense. The Russian fighter jets enjoyed the same “traditional high seas freedoms” advocated by the U.S., for instance, to scramble, to identify or intercept unknown aircraft in international airspace. In other words, speaking of operations within “international airspace”, regardless of whether an ADIZ is established or not, and regardless of which country the military aircraft belongs to, the right of one country’s (military) aircraft to identify, escort, or intercept an aircraft (civil or military) of another country comes from such “freedoms”, rather than the domestic legislative authorization or public announcement of an ADIZ by the declaring country. This is a reflection of state sovereignty. In the Commentary on the Law of Prize and Booty/De Jure Praedae Commentarius (1604), Hugo Grotius, who has been considered by the academia as the “father of modern international law”, pointed out that “Truly, there is no greater sovereign power set over the power of the state and superior to it”[13]. In an article analyzing the basic logic of ADIZs, Jonathan G. Odom, an American military expert, pointed out that “it may reduce the number of ‘aircraft of interest’ the State needs to monitor actively”.[14] Most of the ADIZ rules, such as requiring civil aircraft to file flight plans, are utilized for the convenient identification of aircraft. By the method of exclusion, the real security threats can be easily distinguished from normal flights of civil aircraft. That is to say, when a civil aircraft is normally operating along its flight route under certain ADIZ rules, it is reasonable for relevant air defense units to take it as nonthreatening, and devote their considerable assets to monitoring and dealing promptly with abnormal air situations on radar (e.g. scrambling fighter jets to identify unknown aircraft if required). In addition, some Western experts accused China of potentially using the South China Sea ADIZ “as a way of justifying more air patrols there”.[15] By saying that, they have completely gone against the common sense. According to their logic, can’t Russia, which has not declared any ADIZ, “legally” increase air patrols in the “international airspace” adjacent to its national airspace? Are the “freedoms of navigation and overflight” only applicable to the U.S. and its Western allies?

Fourth, the existence of ADIZs may enhance protection for normal flights of civil aircraft. Due to their authors’ inexperience of ADIZ-related international practices, multiple omissions and errors are found in the above-mentioned media reports. The Economist, for instance, said that “at least half a dozen other countries now also have such zones”. But the truth is that the quantity is more than twenty[16]. It also accused that, based on nothing rational, China may use its ADIZ to disrupt civilian air-traffic,[17] which has also reflected the author’s unawareness of other relevant countries’ practices in regard of ADIZ rules. As a matter of fact, the U.S. has implemented rules that are much stricter than China’s, and has explicitly indicated that civilian aviators’ noncompliance “may result in the use of force”[18] if they fail to “comply with ICAO standard signals relayed from the intercepting aircraft” while operating within “Defense Area” or some part of established ADIZs. Beyond many people’s knowledge, the U.S. has focused greater attention on drug trafficking and terrorist attacks when amending its ADIZ rules from the 1980s, and especially in response to 9/11. The U.S. not only allows its DoD aircraft, but also aircraft of US Coast Guard and Customs Service to “intercept” suspected aircraft. In reality, it is beneficial for civil aircraft conducting normal flights to follow ADIZ rules, not only for their own security but also for avoidance of unnecessary “interception” risks. It is worth noting that it costs enormously for a fighter jet to scramble and perform “interception”. Unless with sufficient evidence to suspect a civil flight of imposing a serious threat to national security interests, it would be unwise to scramble fighter jets to identify flying objects from the perspective of cost effectiveness.

Last but not least, had the U.S. military successfully “challenged” China’s East China Sea ADIZ? Current reports or criticism often quote analysis by some American experts[19] and wrongfully described the U.S. bombers flying through the East China Sea ADIZ “without permission”[20] as a challenge to China’s ADIZ rules. The truth is, however, there is no direct evidence that the East China Sea ADIZ rules announced by China in 2013 require any “permission” for aircraft entering into the zone; nor do they apply to state aircraft as well (according to the Chicago Convention, “aircraft used in military, customs and police services shall be deemed to be state aircraft.”[21]). China’s East China Sea ADIZ rules use the expression of “aircraft” as applicable targets, it is the same expression as used for defining an ADIZ in Annex 15 to the Chicago Convention. Somewhat confusingly, current U.S. ADIZ rules define the applicable targets by using a very ambiguous expression—“all aircraft”, which is misleading but has been interpreted as those including all “civil aircraft” and only some American “public aircraft” (i.e. excluding foreign state aircraft)[22]. The U.S. not only spared no effort to conceal the ambiguity of its ADIZ rules, but also “intentionally” (if not by mistake) misinterpreted China’s East China Sea ADIZ rules as “excessive maritime claim”. From 2014 to 2018, the U.S. military has taken advantage of so-called “Freedom of Navigation Operations”[23] to “challenge” the East China Sea ADIZ, which is the most frequently challenged one among all ADIZs in the world according to public data. In fact, what the U.S. has been challenging is nothing but an imagined enemy. Just like Don Quixote made his attacks against windmills that he saw as giants, the U.S. has always fantasized China’s East China Sea ADIZ as a “monster”. Interestingly, the U.S. has kept silent on ADIZs established by other countries or regions, even if some of them are real “monsters”. For instance, South Korea has made clear that its ADIZ rules require military aircraft to file flight plans, and also apply to state aircraft transiting South Korea’s ADIZ without entering sovereign airspace.[24] The U.S. maybe has “intentionally” overlooked South Korean ADIZ rules, although this kind of ADIZ regime is contrary to the “traditional high seas freedoms” that the U.S. claims for military aircraft, and should be categorized as an “excessive maritime claim” that undermines the “international rules”. Instead of criticizing or challenging such rules of South Korea, the U.S. once paid much compliments (as mentioned above) on the contrary.

This article aims to point out the technical flaws in some think-tanks and media’s reports regarding China’s ADIZ, hoping to help avoid strategic misjudgments caused by which. The arguments in this article are solely for the purpose of clarifying legal facts rather than stating the authors’ position. Media, scholars and officials of foreign countries are free to analyze and interpret China’s policies towards the South China Sea and get their own conclusions, under the premise of “respecting the facts” though. Be cautious of becoming another Don Quixote when pointing fingers at a “potential claim” raised by China. Meanwhile, they may need to be aware of a bias: “any country but China is allowed to establish an ADIZ; any ADIZ established by China is a threat.” It is such arrogance and a blatant practice of double standards in the view of Chinese experts and citizens.

Reference

[1] See “民进党当局要炒作‘南海防空识别区’?跟风美国其心可诛!”,中国台湾网,2020年5月8日,http://www.taiwan.cn/plzhx/plyzl/202005/t20200508_12272743.htm。

See also “China to set up ADIZ in South China Sea”, Taiwan News, May 5, 2020, https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3928503.

[2] Minnie Chan, “Beijing’s plans for South China Sea air defence identification zone cover Pratas, Paracel and Spratly islands, PLA source says,” South China Morning Post, May 31, 2020, https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3086679/beijings-plans-....

[3] Alexander Vuving, “Will China Set Up an Air Defense Identification Zone in the South China Sea?,” The National Interest, June 5, 2020, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/will-china-set-air-defense-identifi....

[4] “Identify yourself - China’s next move in the South China Sea: Is it about to claim the skies above it?,” The Economist, June 18, 2020, https://www.economist.com/china/2020/06/17/chinas-next-move-in-the-south....

[5] “Special Briefing with General Charles Q. Brown, Jr. Pacific Air Forces Commander (PACAF),” the website of U.S. Department of State, June 24, 2020, https://www.state.gov/special-briefing-with-general-charles-q-brown-jr-p....

[6] “2020年6月22日外交部发言人赵立坚主持例行记者会”,外交部网站,2020年6月22日,https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/web/fyrbt_673021/t1791135.shtml。

[7] Before July 2000 amendment, there had been no mention of ADIZ in Annex 15 to the Chicago Convention. In other words, until 2000 amendment to Annex 15, there had been actually not any mention of ADIZ in any international instrument. It is worth noting that Annexes to Chicago Convention include varied Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs) which are technical specifications adopted by the Council of ICAO in accordance with Article 37 of Chicago Convention. SARPs do not have the same legally binding force as the Convention itself, because Annexes are not international treaties—they are just for convenience designated as “Annexes to this Convention” according to Article 54 of the Convention; and according to Article 38, any contracting State has the right to “adopt regulations or practices differing in any particular respect from” any such international standard or procedure. Based on the above, although Annex 15 is not legally binding, its 2000 amendment has some significance in adding the definition of ADIZ and related “Recommended Practices” (all of which have been inherited by subsequent versions of Annex 15 to date.). Moreover, when the U.S. established ADIZs in 1950, there had been not Annex 15, SARPs of which were first adopted by the Council on 15 May 1953 as Annex 15 to the Convention (The first Annex 15 became applicable on 1 April 1954.). See Annex 15 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation, 15th Edition, July 2016, pp. ix, xiv; see also Convention on International Civil Aviation, Art. 37, 38, 54.

[8] Annex 15 to the Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation, Amendment 37, 14th Edition - July 2013, Chapter 1. Definition.

[9] “Air defense identification zone (ADIZ) means an area of airspace over land or water in which

the ready identification, location, and control of all aircraft (except for Department of Defense and

law enforcement aircraft) is required in the interest of national security.” See 14 CFR (2005-2018), §99.3.

[10] J. Ashley Roach, “Air Defence Identification Zones” in R. Wolfrum (ed.), The Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law, Article last updated: March 2017, para. 1.

[11] Le Duy Tran, “Scenarios of the China’ s ADIZs above the South China Sea,” Journal of East Asia and International Law, 9(1), May 2016, pp. 284-285.

See Ankit Panda, “Is China Really About to Announce a South China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone? Maybe - But maybe not.,” The Diplomat, June 1, 2016, https://thediplomat.com/2016/06/is-china-really-about-to-announce-a-sout....

See also Roncevert Ganan Almond, “South China Sea: The Case Against an ADIZ,” The Diplomat, September 13, 2016, https://thediplomat.com/2016/09/south-china-sea-the-case-against-an-adiz/

See also “Identify yourself - China’s next move in the South China Sea: Is it about to claim the skies above it?” The Economist, June 18, 2020, https://www.economist.com/china/2020/06/17/chinas-next-move-in-the-south....

[12] Jen Psaki, Spokesperson, Daily Press Briefing, Washington, DC, December 9, 2013.

[13] Hugo Grotius, Commentrary on the Law of Prize and Booty, Edited and with an Introduction by Martine Julia van Ittersum, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2006, p. 47.

[14] Jonathan G. Odom, “A ‘Rules-based Approach’ to Airspace Defense: A U.S. Perspective on the International Law of the Sea and Airspace, Air Defense Measures, and the Freedom of Navigation,” REVUE BELGE DE DROIT INTERNATIONAL, 2014/1 – Éditions BRUYLANT, Bruxelles, p. 74.

[15] Edmund J. Burke and Astrid Stuth Cevallos, In Line or Out of Order? China’s Approach to ADIZ in Theory,

California: RAND Corporation, November 2017, p. 19.

See also “Identify yourself - China’s next move in the South China Sea: Is it about to claim the skies above it?” The Economist, June 18, 2020, https://www.economist.com/china/2020/06/17/chinas-next-move-in-the-south....

[16] It is particularly worth noting that several Latin American countries have declared their ADIZs in recent years. See Jinyuan Su, “The Practice of States on Air Defense Identification Zones: Geographical Scope, Object of Identification, and Identification Measures,” Chinese Journal of International Law, Vol. 18, Issue 4, 2019, p. 815.

[17] “Identify yourself - China’s next move in the South China Sea: Is it about to claim the skies above it?” The Economist, June 18, 2020, https://www.economist.com/china/2020/06/17/chinas-next-move-in-the-south...

[18] Federal Aviation Administration, Aeronautical Information Manual: Official Guide to Basic Flight Information

and ATC Procedures, October 12, 2017, 5-6-13.

[19] See Michael Green, Kathleen Hicks, Zack Cooper, John Schaus, and Jake Douglas, Countering Coercion in Maritime Asia: The Theory and Practice of Gray Zone Deterrence, CSIS, May 2017, p. 160.

See also Alan D. Romberg, “Maritime and Territorial Disputes in East Asian Waters: An American Perspective,” in Richard Pearson (ed.) East China Sea Tensions: Perspectives and Implications, The Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation, Washington, D.C., 2014, p. 66.

See also Mark J. Valencia, “Troubled Skies: China’s New Air Zone and the East China Sea Disputes,” Global Asia, December 16, 2013, https://www.globalasia.org/v8no4/feature/troubled-skies-chinas-new-air-z....

[20] “Identify yourself - China’s next move in the South China Sea: Is it about to claim the skies above it?” The Economist, June 18, 2020, https://www.economist.com/china/2020/06/17/chinas-next-move-in-the-south....

[21] Convention on International Civil Aviation, Done at Chicago on the 7th Day of December 1944, Article 3.

[22] At first (1950-1960), the U.S. blurred the distinction between civil and military aircraft in terms of ADIZ rules applicability, but from 1961 to 2003 it made clear that the rules only apply to civil aircraft. Though in 2004 U.S. ADIZ regulations were amended to indicate that the rules applied to “all aircraft (except for Department of Defense and law enforcement aircraft)”, it can be inferred from practice and related domestic legal documents that the regulations are not applicable to state aircraft operating outside U.S. territorial airspace. See CAO Qun, The U.S. Air Defense Identification Zones: A Historical and Legal Study, Beijing: China Ocean Press, 2020, p. 3.

[23] US DoD Annual Freedom of Navigation (FON) Reports, https://policy.defense.gov/OUSDP-Offices/FON/.

[24] Ian E. Rinehart and Bart Elias, China’s Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ), CRS Report R43894, Congressional Research Service, January 30, 2015, p. 4.