Washington has been repeatedly accusing Beijing of engaging in gray zone competition against the US since 2015. Specifically, regarding maritime security, Washington has mainly criticized Beijing for its so-called “maritime militia” operations, and construction and militarization of artificial islands and reefs in the South China Sea. The term “gray zone,” however, is not a new concept. The US itself has always been a master of gray zone competition, conducting all sorts of maritime gray zone operations against China as well, which include propaganda campaigns, Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs), and forward military deterrence.

The US Concept of the “Gray Zone” :Enforced Loosely with Itself but Strictly with Others.

It is obvious that the US often uses gray zones to describe the competitive actions of its rivals, while avoiding the term when it comes to its own behavior. This is because the concept, like revisionism, is essentially political rhetoric used by Washington, which is lenient with itself but strict with others. The US often labels its rivals as revisionists while claiming itself as the defender of the existing international order, without reflecting on what it has done to the order. Likewise, the unspoken intention of US accusations is to indicate that other countries are disrupting rules and order, and itself is responding to these challenges and safeguarding international rules and order in a just manner. In other words, its accusations against Beijing undertaking gray zone operations at sea are actually claiming the moral high ground.

In fact, the gray zone is not new, but the normal state of competition among countries. It refers to the ambiguous state somewhere between war and peace. No accurate academic definition has been given yet. At present, the description of the concept in the United States Special Operations Command’s White Paper: The Gray Zone is widely accepted.

Namely, the gray zone consists of “competitive interactions among and within state and non-state actors that fall between the traditional war and peace duality. They are characterized by ambiguity about the nature of conflict, opacity of the parties involved or uncertainty about the relevant policy and legal frameworks.”

According to this definition, gray zone operations have been common throughout human history, inter-state competition and Washington’s historical engagement in foreign affairs. To be more specific, although the US is tight-lipped about its own gray zone actions, some of its scholars argue that the country itself is the “original gray-zone disruptor.” Washington’s competitive actions against China in maritime security also conforms to the general characteristics of the term.

Washington’s maritime gray zone actions against China are ambiguous, progressive, coercive and dangerous. Generally speaking, the term refers to competition and strategies below the threshold of traditional war, yet gray zone competitors do not refuse the use of force. Unlike conventional competition, however, competitors do not seek to accomplish their goals all at once in one battle but to play an asymmetrical advantage via ambiguous, progressive and coercive means. As a master of gray zone competition, the US has not only precisely revised the international maritime order based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to match its expectations and serve its interests, but has also frequently taken various coercive gray zone measures to undermine its rivals, and even resorted to repeated use of varying degrees of force.

Manifestations of Maritime Gray Zone Competition against China

The US enjoys asymmetrical competitive advantages over China in maritime competition. With the rise of China, the US has begun to consider China as its primary revisionist adversary, arguing that China seeks to challenge US maritime leadership in the Indo-Pacific, particularly the South China Sea, and to eventually establish a China-led Indo-Pacific order. The US military repeatedly claims that “China is now capable of controlling the South China Sea in all scenarios short of war with the United States.” Nevertheless, Washington still has prominent asymmetrical advantages over Beijing in public opinion, overall military capabilities and allies. It has continuously brought these advantages into full play to attack China’s weak points and to compete with China over the maritime gray zone.

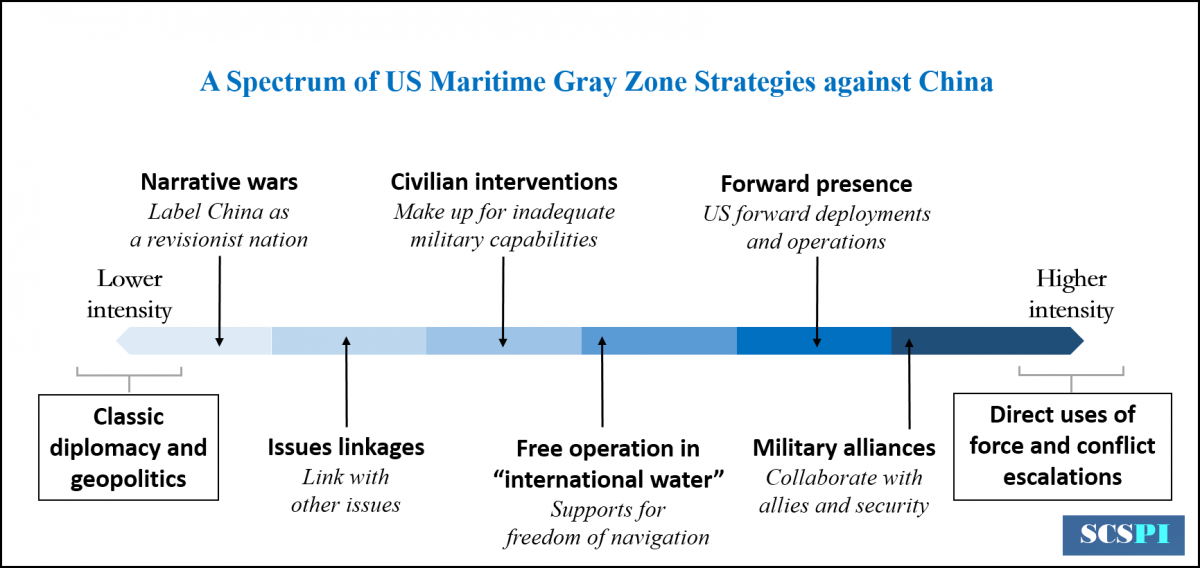

Washington’s various maritime gray zone operations against Beijing below the threshold of direct use of force can be largely divided into six types according to the intensity of the competition. According to the spectrum of gray zone techniques proposed by Michael Mazzar, a scholar in the US Army, there are six types of possible gray zone actions. We can sketch out the basic outline of US maritime gray zone competition against China (Figure 1). Many of Washington’s gray zone operations fall into the following six basic strategies:

Figure 1 A Spectrum of US Maritime Gray Zone Strategies against China

The first strategy consists of narrative wars. The US employs its discourse advantage to label China as a revisionist state in maritime order and other broader issues, accusing China of disrupting the international maritime order via gray zone means, such as military modernization, aggressive military operations and artificial island and reef construction. Meanwhile, the US has been justifying the legitimacy of its revision of the international maritime order and asserting its role in maintaining the status quo to defend its gray zone strategy.

The second strategy consists of issue linkage. The US might link issues like trade, overseas investment and the Taiwan issue to maritime security. In this way, the US can both reduce its own cost of competition and increase the risks that China has to face. Nevertheless, gray zone competition can be ambiguous, making it difficult to test the effect of this technique. It is also highly uncertain how China will respond to such attempts.

The third strategy consists of civilian interventions. Due to its limited functions and size, the US military cannot adequately respond to China’s gray zone competition. The US can make up for such deficiencies, however, through civilian force and activities. It can be best exemplified by its sending of US Coast Guard to the South China Sea, as well as US Navy research vessels to visit Taiwan. In addition, attention should also be paid to US sanctions against Chinese enterprises and individuals.

The fourth strategy consists of US naval and air forces’ free operation in so-called international water. US vessels and aircraft enjoy freedom of navigation and overflight according to international law, but US FONOPs and its other activities, however, are based on its targeted revision of the maritime rules. FONOPs are a common military tool used by the US to maintain the US-led maritime order in key and sensitive waters by challenging the so-called “excessive maritime claims” with its superior naval and air forces. At present, the US is conducting FONOPs in the South China Sea against China more frequently with much greater intensity and exposure.

The fifth strategy consists of forward presence. In order to contain China and its rapidly growing military power, the US has increased its forward military presence. Specifically, it has stepped up military navigation, training, reconnaissance and exercises, and has even engaged in provocative actions in the South China Sea, the Taiwan Strait and other forward areas. In the meantime, taking China as its major imaginary enemy, the US military has increased military deployments to the West Pacific region and adjusted its military strategies and tactics based on changes in its forward situation and in preparation for war.

The sixth strategy consists of military alliances. The US has edged on its allies and security partners to its side in response to challenges from China. Washington is especially prone to nudging countries involved in maritime disputes with China to adopt tough China policies. It also wishes to hold forward military bases in certain countries in support of its operations. The US is currently uniting its allies and security partners in the region and beyond to build a new military alliance against China.

Based on its understanding of China’s military strength, the US has adopted differentiated maritime gray zone strategies toward China. In the South China Sea, where China’s military capabilities have been substantially improved, the US has tried its best to adopt a full-spectrum gray zone techniques to compete fiercely with China; it has also incorporated preparations for war into its gray zone operations, including FONOPs, increased power presence, and military alliances. In comparison, in other Indo-Pacific regions where China’s military capabilities are weaker, Washington is competing against Beijing via non-military means, such as narrative wars, issue linkage, and civilian interventions.

The Essence of US Maritime Gray Zone Tactics: Strengthening itself,Containing Others

Washington’s gray zone operations against Beijing aim at protecting its maritime supremacy. In other words, its gray zone tactics are designed to maintain its traditional sea power by more flexible means. For Washington, Beijing is challenging its maritime dominance. This judgment is not based on China’s intentions or actual threats, but on China’s military capabilities, particularly its anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) capabilities. The US sees China with its rapidly modernizing military as the most threatening challenger to its maritime might in the West Pacific, thus engaging in differentiated gray zone competition against China with a focus on the South China Sea in a bid to curb the rise of China’s maritime power.

Conceivably, the intention of the US is to undermine China’s gray zone advantages. With its geographical advantages, China’s various navy-dominated maritime forces can cover the first island chain with ease; with its strong economic strength, China can reshape the geopolitical architecture of the Indo-Pacific region. The above are the advantages that China enjoys in its gray zone competition with the US. That is why the US has taken the following military actions: regular FONOPs and operations for presence, military reconnaissance, intelligence gathering, training, exercises, battlefield construction, the verification of operation concepts, and deterrence operations.

Meanwhile, the US has not only sent its Coast Guard to the South China Sea, but also built a new military alliance with countries in the region and beyond. Unlike its intensive military gray zone operations in the South China Sea, the US is following non-military and preventive gray zone tactics in the broader Indo-Pacific region in response to China’s economic activities and China’s possible intent to shape geopolitics with economic leverage. Furthermore, both on the South China Sea issue and other broader Indo-Pacific maritime security issues, the US is making use of its advantage in public opinion to depict Beijing as a challenger to current maritime security and Washington as a protector of the current order. All of these US attempts are targeted at undermining China’s gray zone advantages and thus forcing China to accept the US version of international maritime order. Besides the direct hedging operations above, some indirect propagandistic, diplomatic and military tactics are involved to force China to tie the hands and give up some originally effective tools and operations.

The ongoing escalation of gray zone competition will inevitably lead to substantial military conflicts. Apart from gray zone competition with China, the US is also preparing for war against China at sea. Some of these preparations fall into military gray zone operations, such as military reconnaissance, intelligence gathering and battlefield construction. Others include the expansion of military force against China, its primary imaginary enemy. One such example is the US navy’s “Return to Sea Control” directive naval building. Notably, Admiral Harry Binkley Harris, former Commander of the US Pacific Command, and Admiral Philip Davidson, current Commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command, have both warned their country of the threat of war with China triggered by security competition in the South China Sea; Admiral John M. Richardson, then Chief of Naval Operations, warned that Washington would not treat China’s coast guard or maritime militia differently from the Chinese navy.[10] The tough stance of the commanders and senior navy officials indicates that the US military has the intent and is preparing for the use of force against China while simultaneously engaging in gray zone competition.

Conclusion and Expectations

Based on its cognition of China’s military capabilities, the US has adopted a gray zone strategy toward China at sea. This gray zone competition was in essence security competition. In other words, it was originally designed to cope with China’s growing military strength without directly targeting China’s gray zone operations. The US has been assessing China’s A2/AD capabilities, and has thus decided on a mixture of gray zone tactics that highlight its gray zone advantages while undermining China’s traditional military and gray zone operational advantages. In the South China Sea and the East China Sea, where China’s military capabilities, particularly its A2/AD capabilities, have been significantly improved, Washington has not only adopted full-spectrum gray zone techniques, but also spared no effort to invest military resources or supporting resources to strengthen its forward presence for military containment. The US, however, has not invested much military resources in the outlying areas of the Indo-Pacific, where China’s military reach is virtually absent. Rather, the US has adopted a non-military gray zone approach to contain China.

As China’s military might increases, the US will show increased and more dangerous military responses in its maritime gray zone operations against China. As China forges ahead with military modernization, its A2/AD capabilities that concern the US will be ramped up both in terms of strength and range. For example, from the point of view of Washington, China’s new weapons, including the Dong Feng-17 (DF-17) and the Chang Jian-100 (DF-100) unveiled at the National Day parade celebrating the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, will enhance China’s A2/AD capabilities. Thus, Washington will also overcome this difficulty and further engage in military gray zone tactics against China. In the meantime, these reinforced tactics and the tough stance of the US military may result in an intense response from the Chinese government and military. If so, uncertain military gray zone competition might lead to armed conflicts between the two powers.