In the evening of November 16, 2021, two Philippine supply boats trespassed into waters near Second Thomas Shoal of Spratly islands for delivering supplies to the Philippine warship grounded on the Shoal. The boats, suspected carrying construction materials, were driven away by Chinese Coast Guard. On November 18 Philippine Foreign Affairs Secretary Locsin issued a statement: “Second Thomas Shoal is part of the Kalayaan Island Group (KIG), which is an integral part of the Philippines, as well as the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, and over which the Philippines has sovereignty, sovereign rights and jurisdiction… We do not need permission to do what we need to do on our own territory.

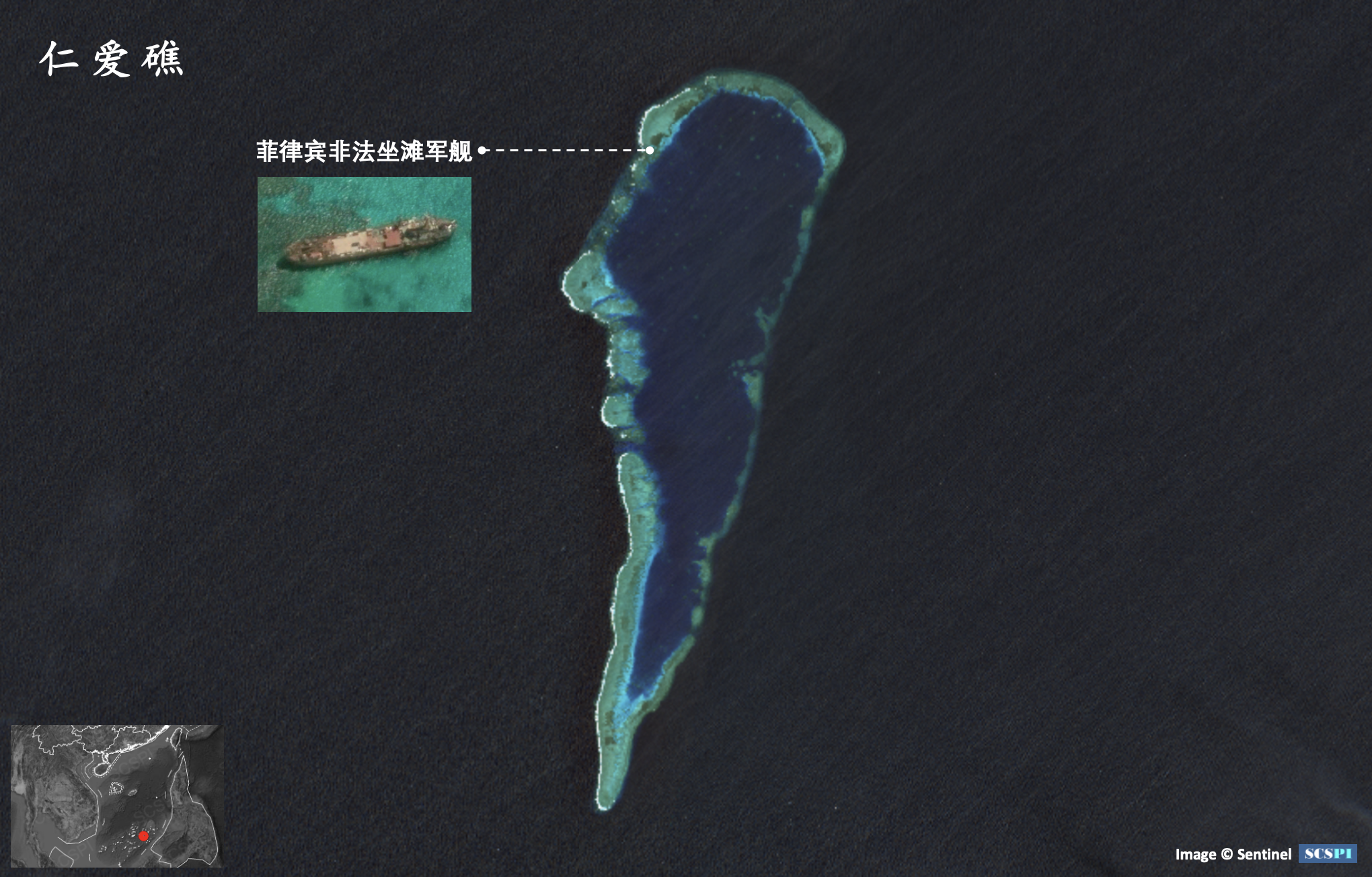

Second Thomas Shoal

Statement of Foreign Affairs Secretary Locsin on the Second Thomas Shoal

On November 19, the US State Department issued a statement, accusing China of actions that “directly threatens regional peace and stability, escalates regional tensions, infringes upon freedom of navigation in the South China Sea as guaranteed under international law, and undermines the rules-based international order.” The United States also claimed that “an armed attack on Philippine public vessels in the South China Sea would invoke the United States mutual defense commitments under Article IV of the 1951 United States -Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty.” China insists that Second Thomas Shoal is part of China's Spratly islands. “China demands that the Philippine side honor its commitment and remove its illegally grounded vessel from Second Thomas Shoal.” As said by China’s Foreign Ministry Spokesperson, “Chinese coast guard vessels performed official duties in accordance with law and uphold China’s territorial sovereignty and maritime order.”

On the Statement in the South China Sea, US State Department

After consultations between two sides, Philippines sent supply ships again to Second Thomas Shoal on November 23. The Chinese side did not stop them this time but monitored the Philippine’s supply activities. As indicated by the China’s spokesperson, “China’s position remains unchanged. This delivery of food and other supplies is a provisional, special arrangement out of humanitarian considerations.”

The resupply incident at Second Thomas Shoal was quickly put to rest due to China’s restraint. The contradicting statements made by the United States and the Philippines however disclosed the nature of the South China Sea disputes between China and Philippines. It is interesting to revisit the Philippines’ previous attitude to the South China Sea arbitration award, the issue of legality of the award, and the reasons and motivations for the US to change its positions.

By the final analysis the disputes between China and the Philippines over Second Thomas Shoal has been always a territorial sovereignty issue, not an issue about legal status of maritime feature. This is proved by the Philippine Foreign Minister clearly mentioned in his statement. “Second Thomas Shoal is part of the Kalayaan Island Group (KIG), which is an integral part of the Philippines.” The previous statements and diplomat notes of the Philippines also repeatedly claimed its territorial sovereignty over the Kalayaan Island Group, which is a modern construct without any historical foundations. On the other hand, China claims Second Thomas Shoal as part of the Spratly Islands, claiming its “indisputable sovereignty over the Spratly Islands and the adjacent waters,” which includes Second Thomas Shoal. Both the 1958 Declaration of the Government of the PRC on Its Territorial Sea and the 1992 Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone clearly state that the territory of the PRC includes Spratly Islands. On May 9, 1999, the Philippines sent BRP Sierra Madre (LT-57), a military vessel, to intrude into Second Thomas Shoal, illegally running it aground on the pretext of “technical difficulties”. China immediately made solemn representations to the Philippines, demanding the immediate removal of that vessel.

China’s position has been consistent. A territorial sovereignty dispute between China and the Philippines clearly exists. It dates back 1970s when the Philippine’s began to make territorial claims on security grounds coupled with actual invasion. The Philippines’ claims obviously came later, given China’s 1958 Declaration. It was not until 2013 that the Philippines abruptly changed its positions, only for winning its unilaterally initiated arbitration proceedings against China. The Philippines disguised the dispute over Second Thomas Shoal as a dispute over the legal status of an individual maritime feature. It contended that Second Thomas Shoal is a low-tide elevation rather than an island with the hope to overcome jurisdictional obstacles based on sovereignty disputes.

Philippines' Diplomatic Note to UN

After the conclusion of the arbitration, the Philippines could not be bothered with such a disguise. Unsatisfied with Second Thomas Shoal just being just part of its exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, the Philippines restarted to claim territorial sovereignty over it. Such a claim was clearly disallowed by the 2016 Award rendered possible by the Philippines’ “previous pretext”. The Philippines’ pick-and-choose attitude towards the Award has been fully exposed when the Award runs against its interests. As known to all international lawyers, no UNCLOS provisions govern the acquisition of territorial sovereignty. UNCLOS dispute settlement mechanisms are only empowered to adjudicate disputes concerning the interpretation or application of the Convention. A territorial sovereignty dispute, like that over Second Thomas Shoal, is clearly not a matter of interpretation and application of the Convention. Throwing away the body of territorial disputes while picking up the remains wrapped up as a maritime entitlement issue, the Award cannot be said to have been well founded in fact and law. The legality and legitimacy of the Award is very questionable.

Can an arbitral tribunal established under the UNCLOS exceed its powers in dealing with territorial sovereignty disputes? Can an UNCLOS dispute mechanism go beyond the scope of the Convention by claiming its authority to determine whether it has jurisdiction? As mentioned above, China and the Philippines have disputed territorial sovereignty over Second Thomas Shoal. And not only this, their territorial disputes extend to the whole area of the Philippines-claimed Kalayaan Island Group. In the South China Sea arbitration, the tribunal disregarded the fact that there was a sovereignty dispute between the two countries and deliberately dismembered the well-recognized geographic unity known as the Nansha or Spratly Islands. The Award misinterpreted the single sovereignty dispute over Second Thomas Shoal and other islands and reefs in the South China Sea as multiple issues of the legal status of individual maritime features. It not only misinterpreted China’s position but also distorted the real position of the Philippines, which has been proved in hindsight. Even if Second Thomas Shoal were to be classified as a low-tide elevation in line with the Award’s logic, whether a low-tide elevation can be appropriated as territory is in itself a question of territorial sovereignty, rather than a matter concerning the interpretation or application of the Convention. The Arbitral Tribunal was well aware that the issue of territorial sovereignty falls beyond the purview of the Convention. Its jurisdiction is limited to the matter concerning the interpretation or application of the Convention. However, the tribunal turned a blind eye to the real position of the parties and exercised jurisdiction over territorial disputes against the principle of State consent. Thus, the award is obviously null and void though its misappropriation of the jurisdiction.

Some Western scholars argue that the Arbitral Tribunal has “the competence of the competence” when its jurisdiction is disputed according to Article 288(4) of the UNCLOS. However, the official position of the claimant, the Government of the Philippines, indicates that the Award has erroneously characterized the dispute. That is, treating a clear matter of territorial sovereignty as not involving territorial sovereignty. It is tantamount to an infringement by the Tribunal on a State’s territorial sovereignty in the name of interpretation and application of the Convention. The tribunal manipulated words to circumvent the lack of the state’s consent so as to seize jurisdiction. This practice sets a bad precedent, which not only seriously undermines the credibility of the dispute settlement mechanism under the Convention, but also violates the right of States parties to choose the means of peaceful dispute settlement out of their free will. The Competence-Competence doctrine, as set out in Article 288(4) of the Convention, has limits of application. That is to say, it cannot go beyond the scope of interpretation and application of the Convention. It cannot adjudicate sovereignty issues under the name of interpretation of the Convention. Legal maneuvers of this nature violate fundamental principles of international law, and go against the object and purpose of the Convention. It is well known that international law is built on the foundation of state consent. The jurisdiction of a court or tribunal in contentious proceedings is also based on the consent of the States involved. UNCLOS tribunals are not empowered to adjudicate disputes over territorial sovereignty, just as; “no State can, without its consent, be compelled to submit disputes to any kind of dispute settlement.”

Article 9 of Annex VII to the Convention provides that the Arbitral Tribunal must satisfy itself not only that it has jurisdiction over the dispute but also that the claim is well founded in fact and law before rendering its award. However, the Tribunal obviously ignored or misinterpreted the fact that China and the Philippines have a sovereignty dispute over the Spratly Islands as a whole. The Tribunal ignored the basic fact that there is also a territorial sovereignty dispute over Second Thomas Shoal, an inherent part of the Spratly Islands, and other islands and reefs in the South China Sea. Adjudicating the issue of territorial sovereignty as a question of the legal status of maritime features cannot live up to the requirement of article 9 of Annex VII. While that was the Philippine’s intent in phrasing its argument as it did, the tribunal should have seen through such a strategy along with its many factual errors, and rejected the entirety of the Philippines request.

The statement made by the United States on the Situation in the South China Sea has once again raised eyebrows of many. It is inconsistent with its commitment not to be involved in disputes over territorial sovereignty of other countries. Besides, the United States’ statement may also violate a fundamental obligation on the prohibition of the threat or use of force against another state under the UN Charter.

As mentioned above, there is no doubt that China and the Philippines have a territorial sovereignty dispute over the Spratly Islands, including Second Thomas Shoal. The United States has repeatedly stated that it takes no position on territorial disputes over islands and reefs in the South China Sea. However, it has now reneged on its prior statements and claimed to stand with its ally, the Philippines, to uphold the so-called “rules-based international maritime order”. The United States turns a blind eye to the territorial claims of the Philippines on Second Thomas Shoal and turns a deaf ear to the sovereignty dispute between China and the Philippines. Oddly, the United States still pretends to defend the Philippines against “an injustice”. These self-contradictory policy statements reveal that the United States has respect neither for the Philippines nor for its own pledges. Its true intent is not for maintaining a “rules-based order”, but for continuing its hegemony. No wonder, just as former presidential spokesperson of the Philippines, Harry Roque has said, “the US, just like in the past, would not offer [the Philippines] any help.” The United States’ policy has gone from not taking a stand on the sovereignty dispute to meddling in the territorial sovereignty and maritime disputes between the Philippines and China. The purpose of shifting policy is not to stand together with ‘allies’ and defend their interests, but for the freedom of operation of its military vessels and aircraft and the free projection of its armed forces as part of a global strategy. In this instance to use the South China Sea as a theater in its attempts to contain China and maintain its hegemony in the region. Moreover, the United States has tried to intervene in the territorial dispute between China and the Philippines under the pretext of the 1951 US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty, which was developed to provide security against fears of further Japanese aggression. In fact, there is also a possible violation of the prohibition of the threat or use of force, as stipulated in Article 2(4) of the UN Charter. Flexing its muscles through the large-scale deployment of warships and military aircraft to the South China Sea, the US is not only violating the territorial integrity of relevant countries, but imposing a threat overshadowing regional peace and stability. It is doubtlessly a violation of both the UN Charter and UNCLOS.

The above contradictory statements made by the Philippines and the United States reveal the greed and dishonesty of the Philippines’ claims in the South China Sea as well as the hegemonic behavior and double standards of the United States. Ironically enough, as the United States and some other Western countries are requesting China to abide by the arbitral ruling, the Philippines has been abandoning the ruling by claiming its territorial sovereignty over single low-tide elevation as part of its Kalayaan Island Group. The flaws of the Arbitral Awards have been fully disclosed. There will be no doubt that the Awards are far from well-founded in fact or law, making it null and void in the eyes of international law.