Twenty years ago… on the morning of April 1, 2001, a United States Navy EP-3 aircraft was conducting close-in reconnaissance on China, about 104 KM (56.1NM) off the southeast coast of China’s Hainan Island, and collided with one People’s Liberation Army Navy J-8 fighter, which was on duty monitoring the EP-3. The collision caused the crash of the J-8, and the death of the Chinese pilot Wang Wei. The damaged EP-3 made an emergency landing at Linshui airport, Hainan. After more than four months of negotiation, the crisis was resolved with US’s apology, compensation and China’s release of the plane and crew. The Sino-US relation was finally put back on the right track. However, US military’s frequent close-in reconnaissance is always one of the three major obstacles to the Sino-US military relations, and has been more and more serious and risky, in the past two decades.

The damaged USN EP-3 landed at Hainan, Apr 1, 2001

As Sino-US military competitions intensify, there has been a sharp increase in the frequency, intensity, and pertinence of US military’s close-in reconnaissance on China since 2009. Nowadays, US flies up to 2,000 sorties of reconnaissance planes to the Yellow, East and South China Seas per year. Meanwhile, they are getting closer and closer. On March 22, 2021, a USAF RC-135U Combat Sent made an unprecedented run at China’s airspace, approaching 25.3 NM from the coast of mainland China; On August 25, 2020, a USAF U-2 flew into a previously declared no-fly zone, where the PLA was conducting live-fire military exercise…

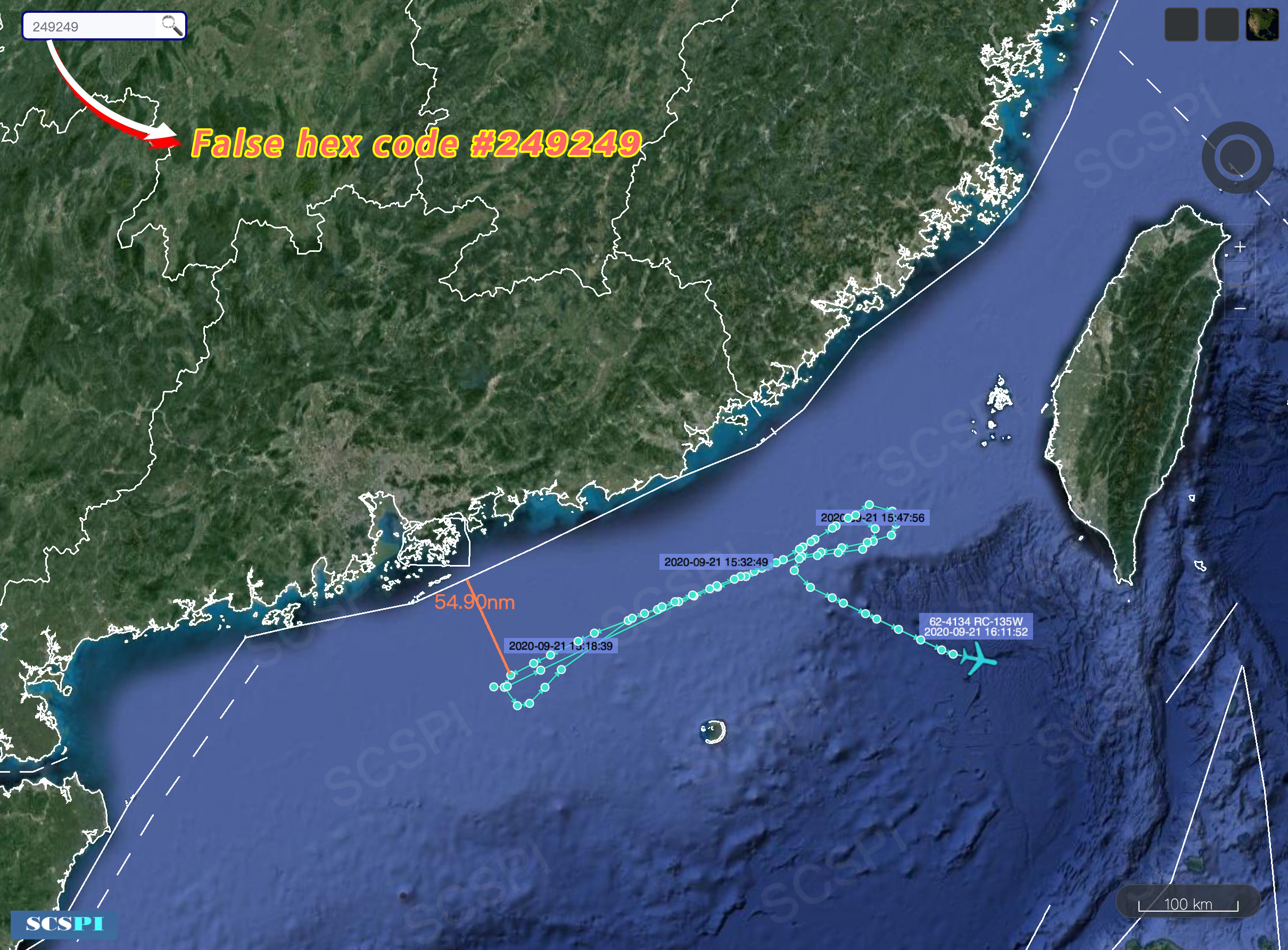

The US reconnaissance activities are also taking on new features. To begin with is the “reconnaissance in disguise”. In 2020, SCSPI found through ADS-B data on multiple occasions that US reconnaissance aircraft impersonated civilian aircraft of countries such as Malaysia and the Philippines by broadcasting spoofed ICAO hex codes to conduct close-in reconnaissance near China’s coast. According to the official data from Chinese authorities, the first three quarters of 2020 had saw US impersonating civilian airliners of other countries for more than a hundred times off the Chinese coast. Such behavior has severely disrupted the aviation order and air safety in relevant airspaces and threatened the security of China and the region, which are highly likely to bring great danger to real airliners, especially to countries that the US impersonated.

USAF RC-135W conducted close-in reconnaissance near Guandong, using a spoofed hex code 249249, Sep 21, 2020

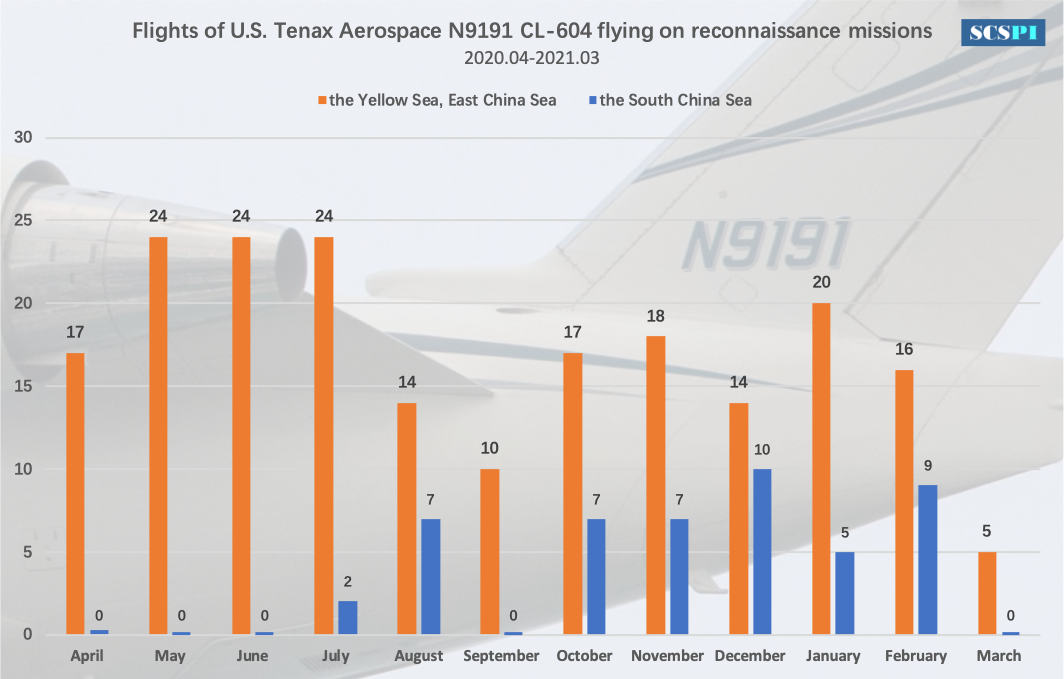

The second is military-civilian fusion. The US military has also begun to hire private defense companies to conduct close-in reconnaissance on China. Among them, a Bombardier CL-604 maritime patrol aircraft of Tenax Aerospace LCC (tail number: N9191), was deployed to Kadena Base in Okinawa, from March 31, 2020 to March 17, 2021, during which it conducted no less than 250 reconnaissance missions on China in one year.

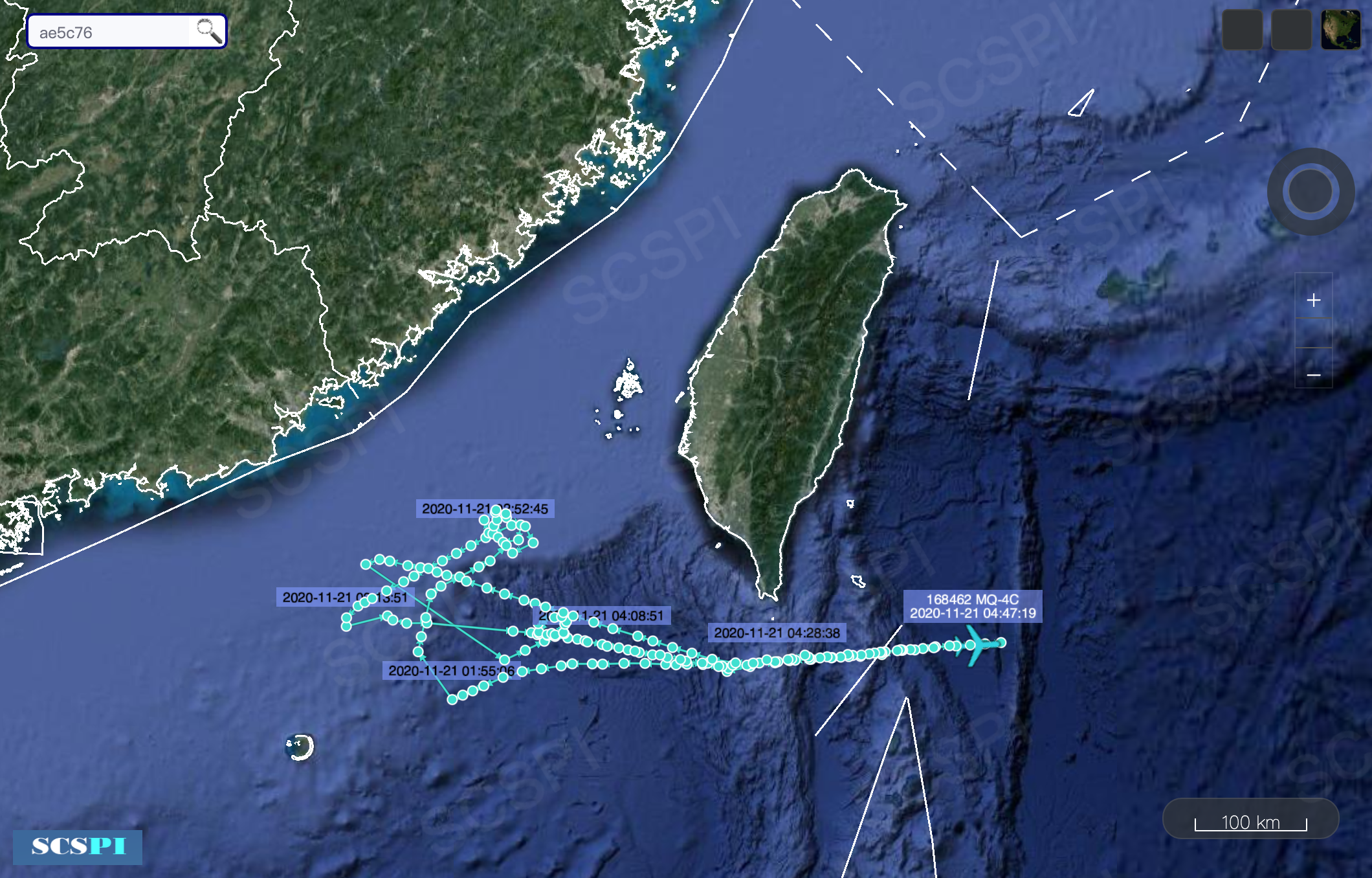

The third is unmanned reconnaissance. RQ-4 Global Hawk and MQ-4C Triton unmanned reconnaissance aircraft have been normally deployed to Andersen Air Force Base, Guam. The MQ-4C, especially, conducts increasingly frequent operations, which are spotted over the South China Sea every two to three days. MQ-4C is replacing EP-3E according to US military plans, and will become the backbone of US reconnaissance forces in the future. The normalized deployment of large-scale unmanned reconnaissance will inevitably increase the risk of misjudgment or friction with Chinese military.

Flight path of USN MQ-4C over the South China Sea, Nov 20, 2020

Regarding the reconnaissance of the airspace off other countries’ territorial waters, the international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, is very much a gray area which has no explicit provisions against such operations. When it comes to the interaction between China and the United States, China requires the United States to “have due regard to the rights” of China and not to menace Chinese national security; while the United States deems that the area outside territorial airspace is international airspace where the operations are totally unrestricted. The US military insists on conducting close-in reconnaissance, and the Chinese military usually adopts measures such as monitoring, accompanying and intercepting according to international practice, depending on the distance.

However, such intensive close-in reconnaissance in peacetime is obviously not a friendly act, which also does not comply with the "the peaceful uses of the seas", Charter of the United Nations and general international laws and norms. What's more, there is a growing tendency that the US intends to exert military and political pressure on China through high-intensity reconnaissance, which has gone beyond the scope of mere intelligence collection. In tactics terms, since the US military has all-round, advanced reconnaissance technologies, such a high frequency aerial reconnaissance and close distance would not be necessary if they are just out of the purpose of gathering intelligence. US officials always ask China to not to overreact on its close-in reconnaissance, but if China sent thousands of reconnaissance aircraft to the east and west coasts of the United States every year, how would the US government, Congress, and the public react? As the US close-in reconnaissance is obviously hostile, China’s opposition is not mainly for legal reasons or intention to control the relevant sea and airspace, but more for security considerations.

The only consensus between the US and Chinese militaries is to strengthen crisis management and avoid uncontrollable military conflicts. US President Biden has made a clear-cut stand that he anticipated steep competition with China, but the US is "not looking for confrontation," which provides a possible opportunity for China and the United States to strengthen crisis management.

In light of the fact that the close-in reconnaissance and the countermeasures between the United States and China have increasingly intensified, the risks exist anytime and anywhere, thus it’s very urgent for the governments and militaries of the two countries to draw up the necessary rules to control competition and avoid friction. China and the United States signed two Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) on confidence-building measure (CBM) mechanism in 2014, namely the “Notification of Major Military Activities” and “The Rules of Behavior for Safety of Air and Maritime Encounter” but neither of which made explicit provisions on "close-in reconnaissance". In the next step, the two sides should conduct in-depth and pragmatic consultations, and make every endeavor to form a series of operational code of conduct for close-in reconnaissance and aerial encounters.

Both sides, especially the US, need to have a certain strategic awareness and exercise necessary restraint. By no means will the United States abandon reconnaissance on China, but it also needs to try reducing the risk of military friction caused by close-in reconnaissance. Although almost all the rules between major powers, especially the rules of military interaction, are the result of violent confrontation and gaming, the current Sino-US relations and the whole world may no longer be able to endure another physical collision and the test of resolutions.