The Changing Background of FONOPs in the South China Sea

Since the Obama administration proposed the “pivot to Asia”, strengthening the US military presence in the South China Sea and other regions has become the main tool or the effective means of the US Asia-Pacific or Indo-Pacific strategy. Since 2009, the US military has continued to increase the frequency, intensity and pertinence of its military operations against China in the South China Sea. The US carrier strike groups (CSGs), amphibious ready groups (ARGs), bombers, large reconnaissance aircraft, fighters and even submarines frequently enter the South China Sea, which has attracted extensive attention from international public opinion and academic circles. Studies and comments on this issue are numerous. However, less attention has been paid to the changing narratives and politicization trends associated with these military operations. What is intuitive is that US military operations are gaining greater visibility, and related narratives are becoming increasingly high-profile and complex. The freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs), conducted within 12 nautical miles of the Spratly Islands, or the territorial waters of the Paracel Islands, had existed for a long time before 2015, but were rarely known to the public. But after that, it has been applied as a political tool to put overt pressure on China.

The US side has repeatedly claimed that “the United States will fly, sail and operate wherever international law allows, as we do around the world, and the South China Sea will not be an exception.”[1] As for the FONOPs in the South China Sea, the US also stressed that they are not solely directed at China, but challenge what the US views as “excessive maritime claims” made by other states around the world, claiming that it aims to safeguard the “rules-based international order.” But that does not explain the changes in operations, rhetoric and media strategies that have taken place from 2009, especially since 2015. US officials, scholars and news media, are increasingly linking the military operations of US forces in the South China Sea to the overall China-US relationship, and hence, intentionally or unintentionally, the political and strategic significance of those military operations has been highlighted.

Military power is a continuation of politics, and it is not a new topic that military operations, especially naval operations, have political and diplomatic objectives. The question is to what extent the US military operations in the South China Sea have been politicized? And how will the future develop? FONOPs account for a pretty small proportion of the overall South China Sea operations of US forces, and are less frequent and intense than close-in reconnaissance, regular patrols, and other military manoeuvres. However, the feature-challenge FONOPs in the South China Sea are the most visible and politicized military activities of the US forces. Therefore, the operational and narrative characteristics of such FONOPs are highly representative of the politicization process of the overall US military operations in the South China Sea.

The General Elements of US FONOPs in the World

In the late 1970s, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) negotiations were in full swing. In order to cope with the challenges that the new international regime might pose to the global free access of US forces, the Carter administration officially set up the Freedom of Navigation (FON) Program in July 1979, with the purpose of conducting operations to challenge the so-called “excessive maritime claims” of other nations. The FON Program mainly takes two forms: (1) consultations and representations by U.S. diplomats (i.e., U.S. Department of State), and (2) operational assertions by U.S. military forces (i.e., U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) FON Program). “Thus, the program is primarily a legal tool and does not have, on its own, a rationale stemming from strategic calculations such as deterring coastal state behavior.”[2] FONOPs are military assertions. US Navy and Air Force conduct operations to challenge what the US considers to be “excessive maritime claims” by other countries and strengthen “internationally recognized rights and freedoms.” Traditionally, FONOPs are operationally low-intensity and diplomatically low-key. The point is not to menace the target state with gunboats or to upstage them with publicity. Rather, the program asserts the relevant legal norm in word and in deed.[3] But in practice, politics is never absent. FONOPs are highly professional and political undertakings. From route selection, the operation of ships and aircraft during navigation, to the communication with ships and aircraft of coastal states, the training of US military officers and soldiers should be specific to key combat positions. Every command and operation potentially affect the accurate expression of the US signals.[4] During the mission planning phase, relevant officials at the Pentagon, the State Department and the National Security Council can intervene in the name of international politics and foreign policy.

At the narrative level, the US military tends to be secretive about the details of FONOPs. The US Department of Defense releases its annual Freedom of Navigation (FON) Report for the last fiscal year, listing operational assertions that are conducted by the US Navy as part of the program. Nothing in the reports explicitly states the number of operations against each type of excessive maritime claims, much less the timing, location and other details of each operation. While the US military has occasionally released details of some operations in recent years, it is by no means mainstream. According to the FON Reports over the years, there are at least six types of FONOPs against China in the South China Sea: (1) Prior permission required for innocent passage of foreign military ships through the territorial sea; (2) Straight baseline claims (Paracel Islands); (3) Surveying and mapping activities by foreign entities; (4) Territorial sea and airspace around features not so entitled (i.e., low-tide elevations); (5) Security jurisdiction over the contiguous zone; (6) Jurisdiction over exclusive economic zone (EEZ). In addition to operational challenges on islands and reefs in the South China Sea, FONOPs are also conducted on the indisputable territorial waters, contiguous zone and EEZ of the mainland and Hainan Island of China, which has been almost never announced publicly. Furthermore, in terms of the operational trajectories, FONOPs have many similarities with general military presence operations or cruises. Unless the US military confirms or specifies, it is difficult for the outside world to judge whether some particular operations are FONOPs. As a result, it is difficult to ascertain how many FONOPs are conducted against China each year. The number of times that experts calculate based on information released by media and the US military provides only a glimpse. In fact, even the feature-challenge FONOPs statistics are hard to obtain, and the significance of the so-called “number” is not as great as imagined.

The Particularities and Corresponding Explanations of the Feature-challenge FONOPs

On October 27, 2015, the USS Lassen DDG-82 entered within 12 nautical miles of Subi Reef and Mischief Reef, proclaiming a more politicized and high-profile type of FONOPs. Different from the traditional low-key and secretive ones, these blockbusting FONOPs in the South China Sea have been largely exposed to the public. Although US officials have repeatedly emphasized that the FONOP is a global operation where South China Sea gets nothing special, it has undoubtedly been overexposed and politicized. Critics arose even in the US: some scholars believe that FONOPs should stay conventional and low-key instead of getting overhyped.[5]

Since 2015, US FONOPs around China-stationed islands and reefs in the South China Sea are different from not only similar operations in other regions but also FONOPs targeting China's EEZ, air defense identification zone and contiguous zone. Why are there such changes or differences? Though the US side has always declared that “the US will continue to fly, sail, and operate wherever international law allows”, and the South China Sea will not be an exception.[6]

Academics, including American scholars, are inclined to the logic of power politics while examining FONOPs in the South China Sea. Many scholars have related the FONOP to “Asia Pacific Rebalance” and “Indo-Pacific Strategy”, believing that it serves to reshape US leadership in the Asia Pacific region.[7] Some find the freedoms of navigation correlated to the great power competition between China and the US, and it may involve the power struggle between emerging and hegemonic powers, as well as the interaction between the two sides' maritime strategies.[8] As many American scholars also point out, in order to safeguard its hegemony and suppress China as a potential rival, the US side claims that China's statements and operations of maritime rights and interests are “at odd with the norms of the international law of the sea”.[9] Taylor Fravel suggests that US FONOPs in the South China Sea in recent years have the logic of both norms and power, aiming to increase the cost of China’s action and shape China's behavior by taking coercive action and deliberately highlight that China’s behavior “is not in line with the international law”.[10] There are also scholars who associate US FONOPs with its power competition in history —including the Quasi War of 1798, the two World Wars, the Korean War, the Vietnam War and the Libyan war——or extend to the conflict between the US and the Soviet Union on maritime navigation during the Cold War, and the current South China Sea game between China and the US.[11]

Research has noticed the compound logic of FONOPs: strengthen the rules by power projection and serve power projection by rules simultaneously. Backing the logic lies a dual purpose concerning both the liberal international order and the maritime hegemony of the US.[12] When it comes to FONOPs, the US chooses the types of international norms that are conducive to power expansion according to the power logic. As to power factors, it turns to the widely acceptable type following the normative logic.

Although existing research has no direct analysis of the changes and particularity of the US military's FONOPs against China around the islands and reefs in the South China Sea, it is almost a consensus that this kind of behavior is to exert political pressure on China. Arguably, the FONOP against China in the South China Sea are becoming politicized. However, most of these studies or judgments are based on empiricism and lack of necessary empirical support. If the US military's FONOPs around the islands and reefs in the South China Sea have the purpose of exerting political pressure on China in the China-US interaction, these operations will have a clear correlation with the major political agendas of the US, China and the Asia Pacific region in terms of timing. According to the narrative logic of maritime diplomacy, the narrative of US military operations will also show the trend of politicization.

i. The correlation between feature-challenge FONOPs and important agendas in China-US relations

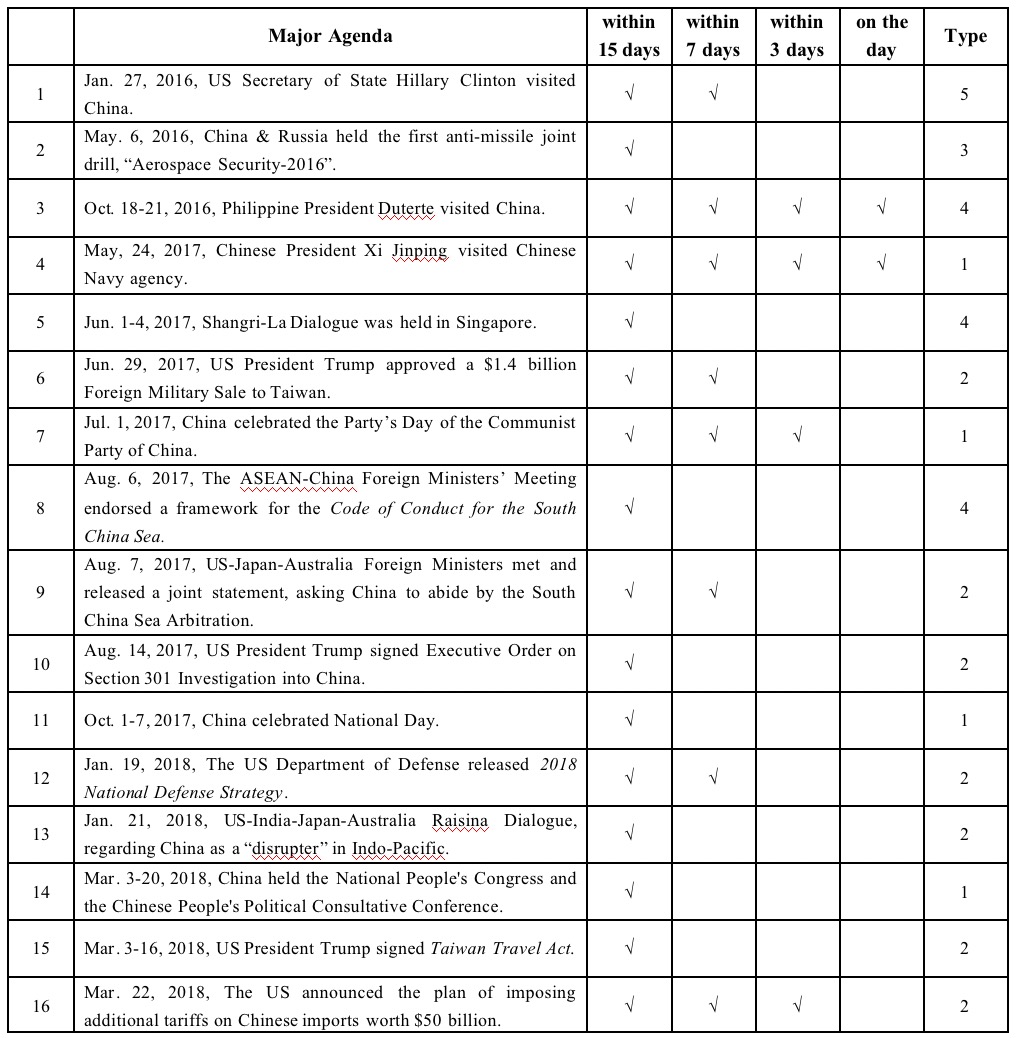

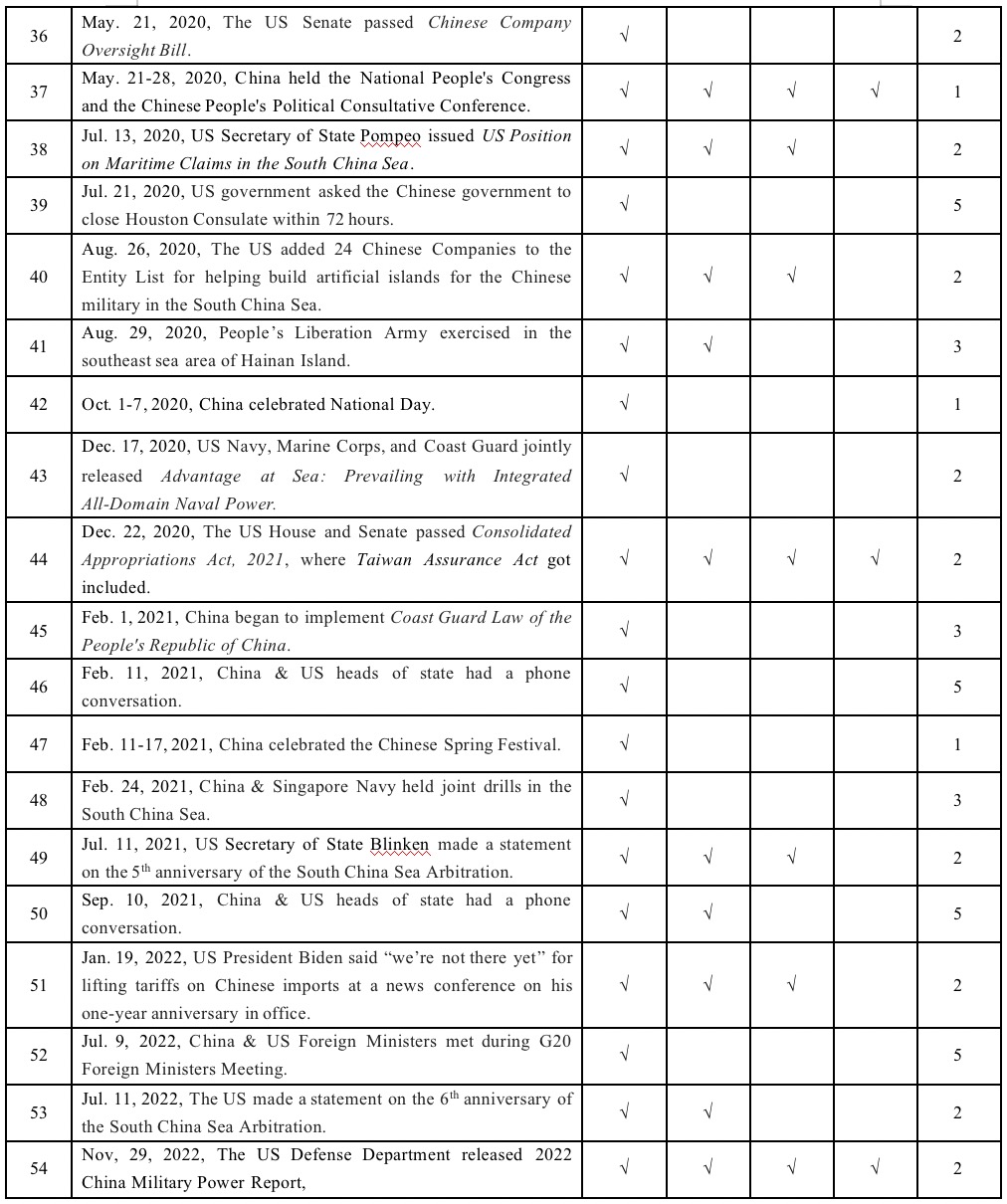

The important agenda in China-US interaction are major events causing military, political, diplomatic and strategic influence. Considering that economic factors are increasingly of strategic significance in China-US relations, the economic agenda with strategic and political influence is also included in the observation sample. Accordingly, the chronicles of China-US relations can be divided into five types: (1) China’s festivals and meetings, including the Spring Festival, the Party’s Day, the National Day, the National Congress and the National People's Congress; (2) Important trends of the US’s China-related and maritime policies, such as the release of the National Security Strategy, National Defense Strategy, the Taiwan Assurance Act, and US trade measures toward China; (3) Important policy trends and major military operations of China concerning the US, including China's trade measures toward the US, military drills of the People's Liberation Army in the South China Sea, and the construction of China's military and civilian facilities on reefs in the South China Sea; (4) Regional hot spots and important international conferences, including the Boao Forum for Asia, the East Asia Summit, the APEC Leaders' Summit, the Shangri La Dialogue, and the DPRK leaders' visit to China; (5) Important bilateral interactions between China and the US, such as the China-US leaders’ meeting and high-level visits. In view of this, this paper combs 39 FONOPs around the islands and reefs occupied by China in the South China Sea that have been publicly carried out by the US military since 2015, and 54 major events of China-US relations that occurred on the same day, within three days (one day before and one day after), within seven days (three days before and three days after), and within 15 days (seven days before and seven days after) of these FONOPs.[13] If these FONOPs are meant to exert pressure or show attitude in the major events of China-US relations, there cannot be long intervals in the time dimension.[14] Furthermore, taking the deployment and operation cycle of warships in and around the South China Sea into consideration, 15 days is the maximum time interval worth measuring.

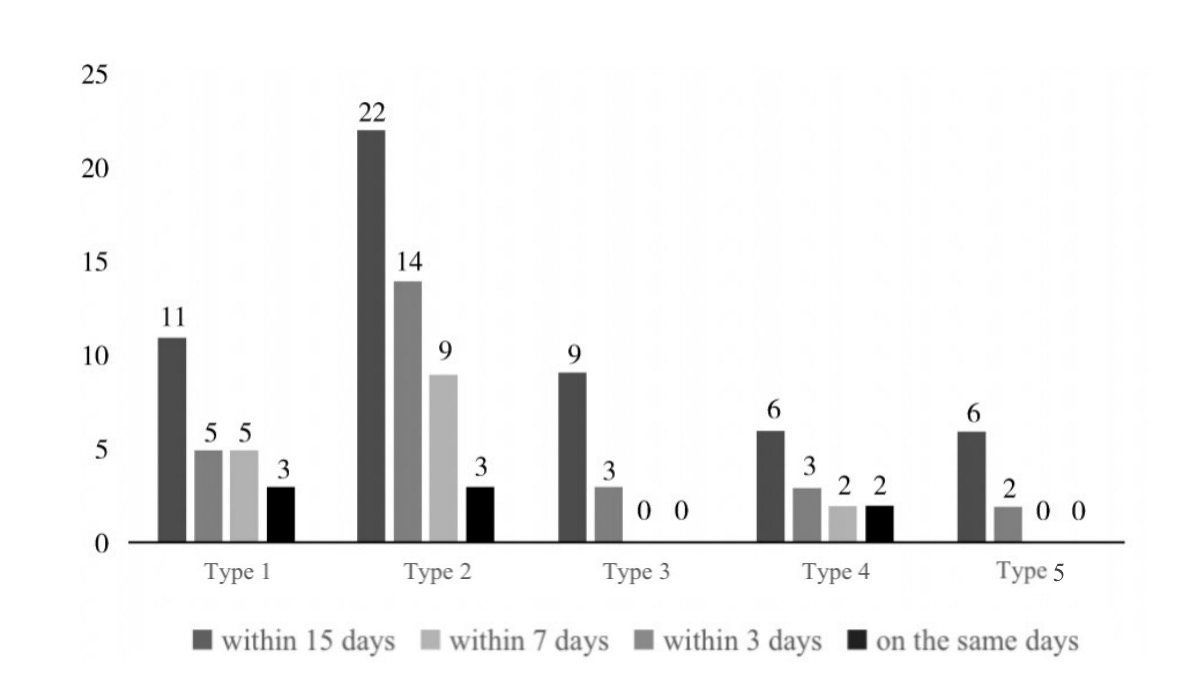

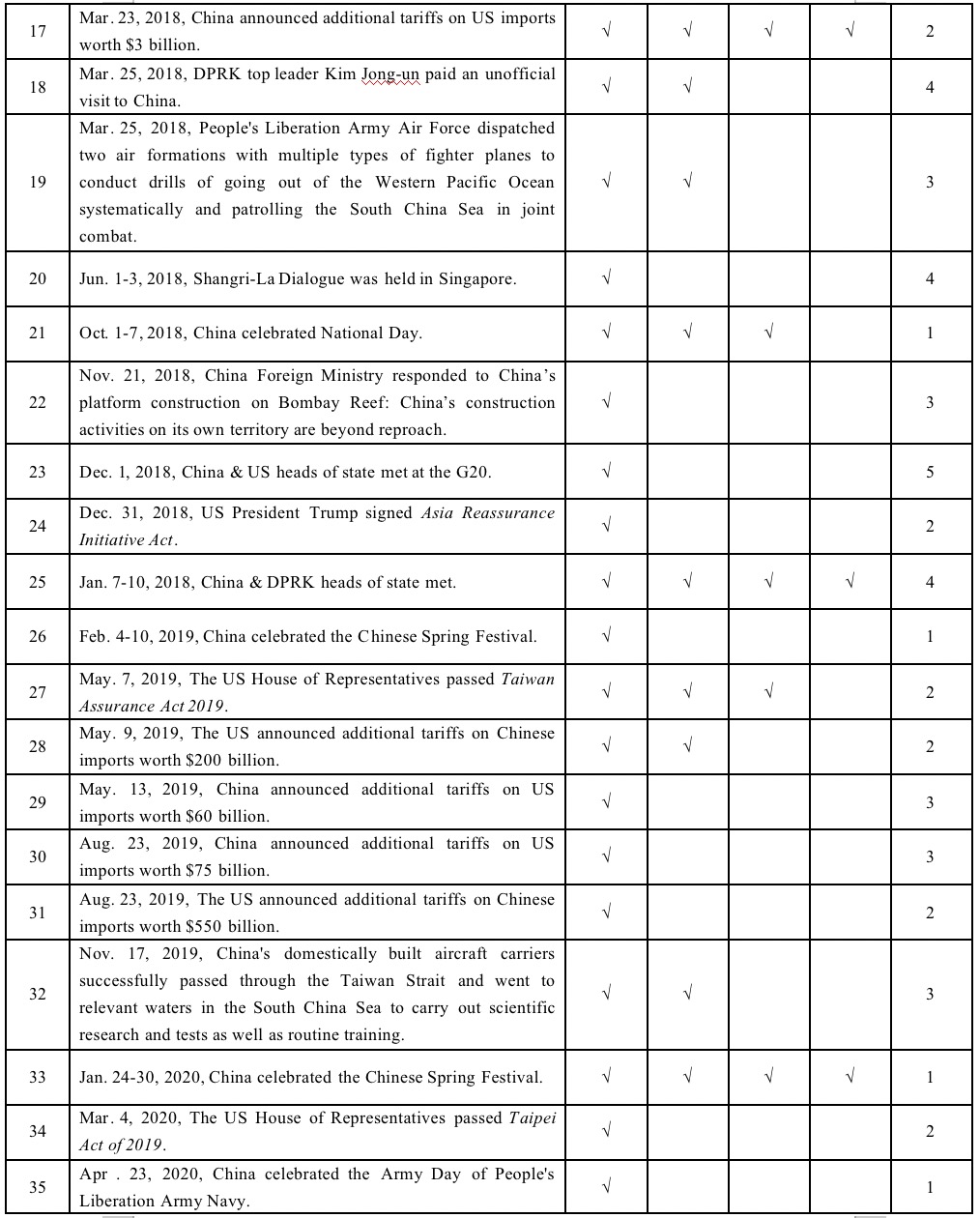

In terms of the type of chronicles of China-US relations, the US’s feature- challenge FONOPs have the highest correlation with “important trends of the US’s China-related and maritime policies”. There were 22, 14, nine and three events respectively within 15 days, seven days, three days and the same day of the 39 FONOPs. “China’s festivals and meetings” ranks second. There were 11, five, five and three events respectively within 15 days, seven days, three days and the same day. Besides, “important policy trends and major military operations of China concerning the US” and "Regional hot spots and important international conferences" are not closely related to the US military FONOPs. There were nine and six events within 15 days, three and three events within seven days, and two "regional hot spots and important international conferences" respectively within three days and the same day of the FONOP. The weakest relevance lies between "important bilateral interactions between China and the US " and the FONOP. Six events occurred within 15 days of the 39 operations, and two events occurred within seven days.

Table 1. The number of various types of chronicles of China-US relations within 15 days, 7 days, 3 days and the same day of the 39 public FONOPs conducted by the US military.

Table Note: Type 1 China’s festivals and meetings; Type 2 Important trends of the US’s China-related and maritime policies; Type 3 Important policy trends and major military operations of China concerning the US; Type 4 Regional hot spots and important international conferences; Type 5 Important bilateral interactions between China and the US

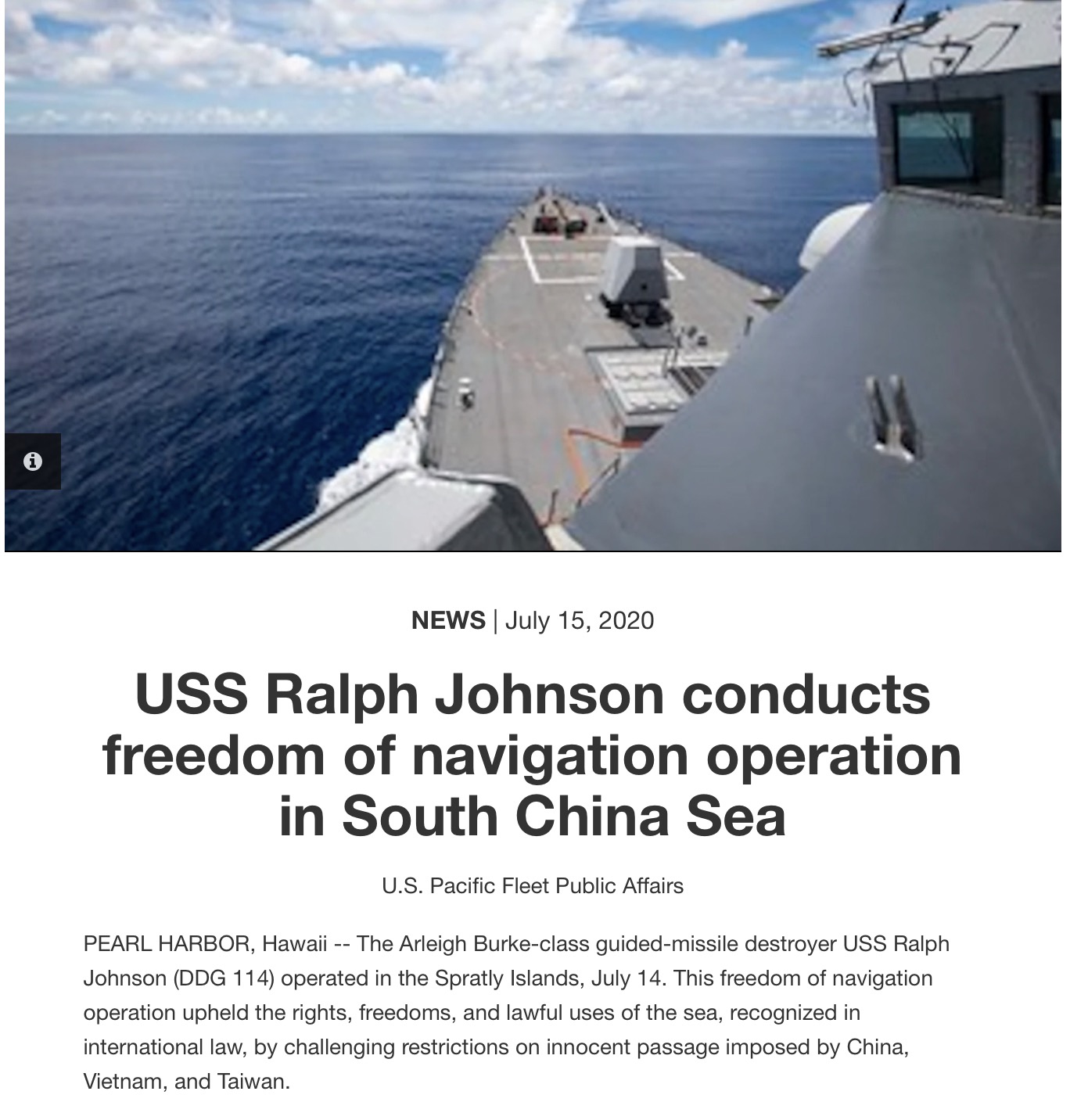

The events of China-US relations within 15 days of a US military FONOP mainly focused on agendas such as the construction of islands and reefs in the South China Sea, the South China Sea Arbitration, the consultation on the "South China Sea Code of Conduct" and China-US trade frictions. Initially, the US FONOP against China around the islands and reefs in the South China Sea was mainly a response to the China’s island reclamation in the Spratly Islands. On May 12, 2015, US Defense Secretary Ashton Carter publicly proclaimed upcoming FONOPs in the waters within 12 nautical miles of the South China Sea islands and reefs where China carried out reclamation. After five months of consultations between the US State Department and the Department of Defense, on October 27, 2015, the USS Lassen DDG-82 entered the waters adjacent to Subi Reef in the Spratly Islands. Since then, the US has repeatedly conducted FONOPs while accusing China of the land reclamation in the South China Sea or issuing the statement of "requiring South China Sea claimants to avoid militarization of maritime features". In response to the verdict on the legal characterization of Mischief Reef as the South China Sea Arbitration ruling, the USS John S. McCain, DDG-56, entered within 12 nautical miles of Mischief Reef in May 2017, stayed for an hour and a half, and conducted life-rescue training. In the statement of FONOPs in September 2021, the US Navy publicly stated that Mischief Reef was a "low tide feature" instead of an island or rock.[15] On July 13, 2020, US Secretary of State Pompeo issued the US Position on Maritime Claims in the South China Sea, referring to the South China Sea Arbitration again. The next day, the USS Ralph Johnson, DDG-114, entered the waters adjacent to the Spratly Islands. Moreover, on July 11, 2021, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken issued a statement on the fifth anniversary of the South China Sea Arbitration, and the USS Benfold, DDG-65, entered the waters adjacent to the Paracel Islands. On the sixth anniversary of the South China Sea Arbitration, the USS Benfold DDG-65 entered the territorial waters of the Paracel Islands and the adjacent waters of the Spratly Islands on July 13 and 16, 2022, respectively.

With the escalation of China-US trade frictions, the US military's FONOPs around the islands and reefs in the South China Sea have become increasingly relevant to the trade agenda. On August 14, 2017, US President Trump launched the Section 301 investigation on China. On March 22, 2018, the US announced the imposition of additional tariffs on Chinese imports worth $50 billion. On March 23, 2018, China announced additional tariffs on US imports worth $3 billion. On December 1, 2018, the leaders of China and the US met and agreed to stop imposing new tariffs on each other. In 2019, the US announced additional tariffs on Chinese imports worth $200 billion and $550 billion, while China announced to impose tariffs on US imports worth $60 billion and $75 billion. All these occurred within 7 days before and after US FONOPs around China-stationed features in the South China Sea.

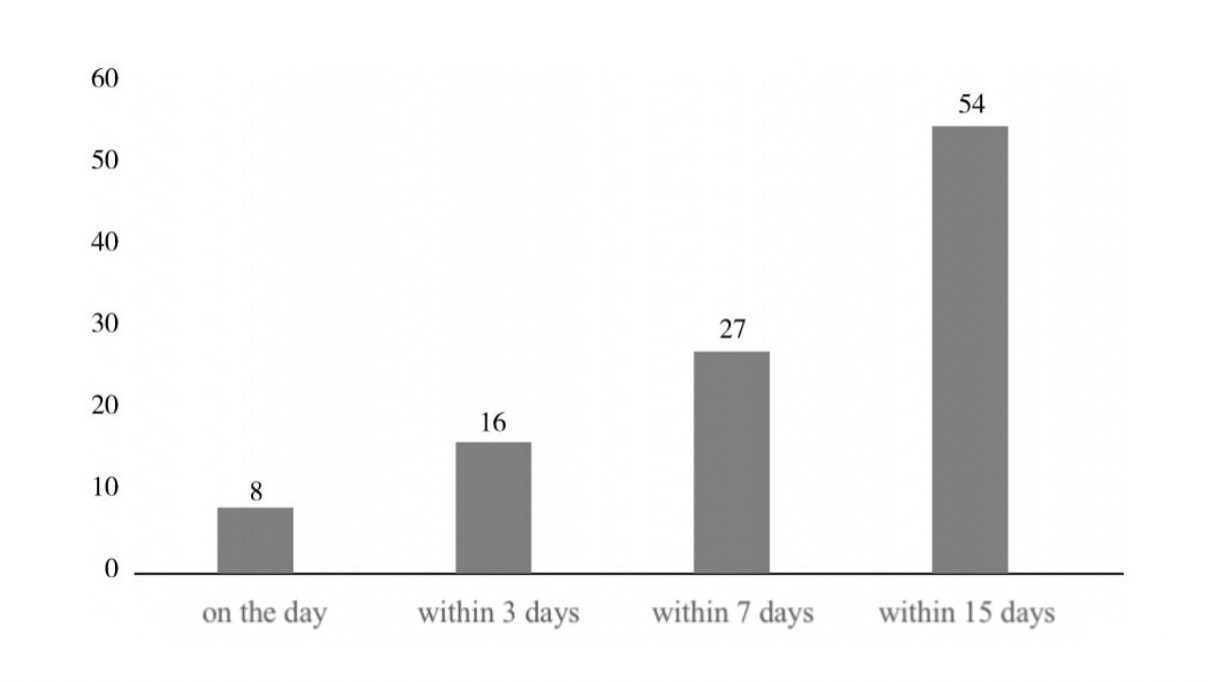

In terms of the time cycle, the major agenda of China-US relations appeared eight times, 16 times, 27 times and 54 times respectively on the same day, within three days, seven days, and 15 days of the 39 FONOPs.

Table 2. The number of times that the major agenda of China-US relations appeared on the day, within three days, seven days and 15 days of US FONOPs (From October 27 of 2015 to November 29 of 2022)

Since 2015, there have been eight important events between China and the US that took place on the day of the US military feature-challenge FONOPs, namely, the visit of Philippine President Duterte to China from October 18 to 21, 2016, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Chinese Navy headquarters on May, 24, 2017, the declaration of China's imposition of tariffs on US imports worth $3 billion on March 23, 2018, the meeting of Chinese and DPRK leaders on January 7, 2019, the Spring Festival on January 25, 2020, China’s two sessions on May 28, 2020, the US House and Senate’s passing the 2021 annual appropriation bill including the Taiwan Assurance Act on December 22, 2020 and the US Defense Department released its annual China Military Power Report on November 29, 2022.

In addition to those that occurred on the same day, there were eight others that happened within three days of the FONOP: the Party’s Day of the CPC on July 1, 2017, the US announcing additional tariffs on Chinese imports worth $50 billion on March 22, 2018, China's National Day on October 1, 2018, the passage of the Taiwan Assurance Act 2019 through the US House of Representatives on May 7, 2019, and the US Position on Maritime Claims in the South China Sea on July 13, 2020. Moreover, the US listed 24 enterprises that “helped the Chinese military build artificial islands in the South China Sea” in the Entity List on August 26, 2020, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken issued a statement on the fifth anniversary of South China Sea Arbitration on July 11, 2021, and US President Biden’s denial of the abolition of additional tariffs on Chinese goods at a news conference on January 19, 2022.

ii. The politicization of the US narrative

The US feature-challenge FONOPs’ transformation from the low-key military declaration to an open and high-profile public opinion warfare is mainly reflected in the following two aspects:

On the one hand, FONOPs publicity has been upgraded from media news to official public statements. Traditionally, the US FONOP is not open to the public, and only the target state gets referred in the annual FON report briefing. Since the USS Lassen DDG-82 entered the adjacent waters of China-stationed features of Spratly islands in October 2015, the US military has begun to actively disclose the details including the performing vessel, time and place of FONOPs against China to Reuters, USNI News and other media. Although not much information gets disclosed, encouraging relevant media to hype has achieved the purpose of preliminary public opinion buildup. On July 14, 2020, the US Indo-Pacific Command stated that the USS Ralph Johnson conducted a FONOP in the South China Sea for the first time, marking the prelude to the official public statements of the US FONOPs.[16] At present, the US Indo-Pacific Command and the Seventh Fleet release official statements of 1,000 words on their official website in pace with each FONOP. The detailed statements, in conjunction with the high-profile media reports, aim to shape the legality and legitimacy of the US FONOPs in the South China Sea, and accuse China of land reclamation and military operations in the region.

On the other hand, with the increasing length of the FONOP statements, the wording gets enhanced intensity and sharpness. In order to test the narrative characteristics of the US FONOP statements, this paper has collated 39 public statements of the US military FONOPs around China stationed features in the South China Sea since 2015, including 11 issued by the US military official website, and combs and counts 11 keywords such as "navigation", "operation", "law", "free", "right", "rule" and "norm", totaling 1249 sample data.[17]

The most frequent expressions in the statements are "navigation" and "operation", with an average frequency of two and four respectively. In the early stage, due to the limited space of public information, the two words appeared less than five times together. From 2020, the frequency of these two has increased to an average of five and 11 times respectively.

The words that reflect the normative logic best are "law" and "free", which are also pivotal topics in the US public statements. The number of references to international law or law increased from five on average between 2015 and 2019 to about 15 since 2020. In the statement on July 21, 2021, the number has reached 32. The frequency of "free" kept at two times per statement from 2015 to 2019. From 2020, it surged to an average of 12 times. The number of "right" mentioned in the statements has increased from an average of once between 2015 and 2019 to five after December 2020. "Rule" and "norm" were mentioned in three statements in January, April and December 2020, but they did not officially enter the discourse of public statements until June 2021, appearing at an average frequency of two to three times.

In the early public statements, "excessive maritime claims" were mentioned twice on average. The number reached nine after 2021. Moreover, in the statement on April 29, 2020, the US notably changed the wording from "excessive maritime claims" to "unlawful and sweeping maritime claims". It is worth noting that when the US referred to the "excessive maritime claim" in the early stage, it did not clearly point out the matters targeted. Instead, the "excessive maritime claims" recognized by the US, such as the delimitation of the territorial sea baseline, the breadth of the territorial sea, the right of innocent passage of warships into the territorial sea and historic waters, were challenged through specific operations. However, in October 2016, the USS Decatur, DDG-73, entered within 12 miles of Triton Island and Woody Island in the Paracels, and the US Navy publicly stated that China's territorial sea baseline in the Paracel Islands was invalid. Since 2021, the US refers to "territorial sea baseline" eight times per statement. The statements in January 2016, January 2018 and November 2018 mentioned "innocent passage" three times in total, but did not go into detail. Since September 13, 2019, "innocent passage" has officially become normal in the statements with an average of six times mentioned. Furthermore, the statement pointed out that "according to the Convention, vessels, including warships, enjoy the right of innocent passage". Starting from the statement on August 27, 2021, the US mentioned its original concept of "international waters" twice on average, trying to use it to replace the terms specified in UNCLOS such as EEZ, contiguous zone and territorial sea.

Conclusion

The operational practice of FONOPs shows that the US military operations in the South China Sea have more political overtones and diplomatic implications. In the narrowing balance of power between China and the US in the South China Sea, the latter has become increasingly anxious and worries that “China will control the South China Sea”. In this context, in addition to the traditional significance, the politicization of military operations also has the consideration of making up for the lack of US strength and giving play to the comparative advantage of US political diplomacy. Undoubtedly, the operational and narrative characteristics of such FONOPs and the politicization of the US military operations in the South China Sea are the major topics that call for much attention and further study in the future.

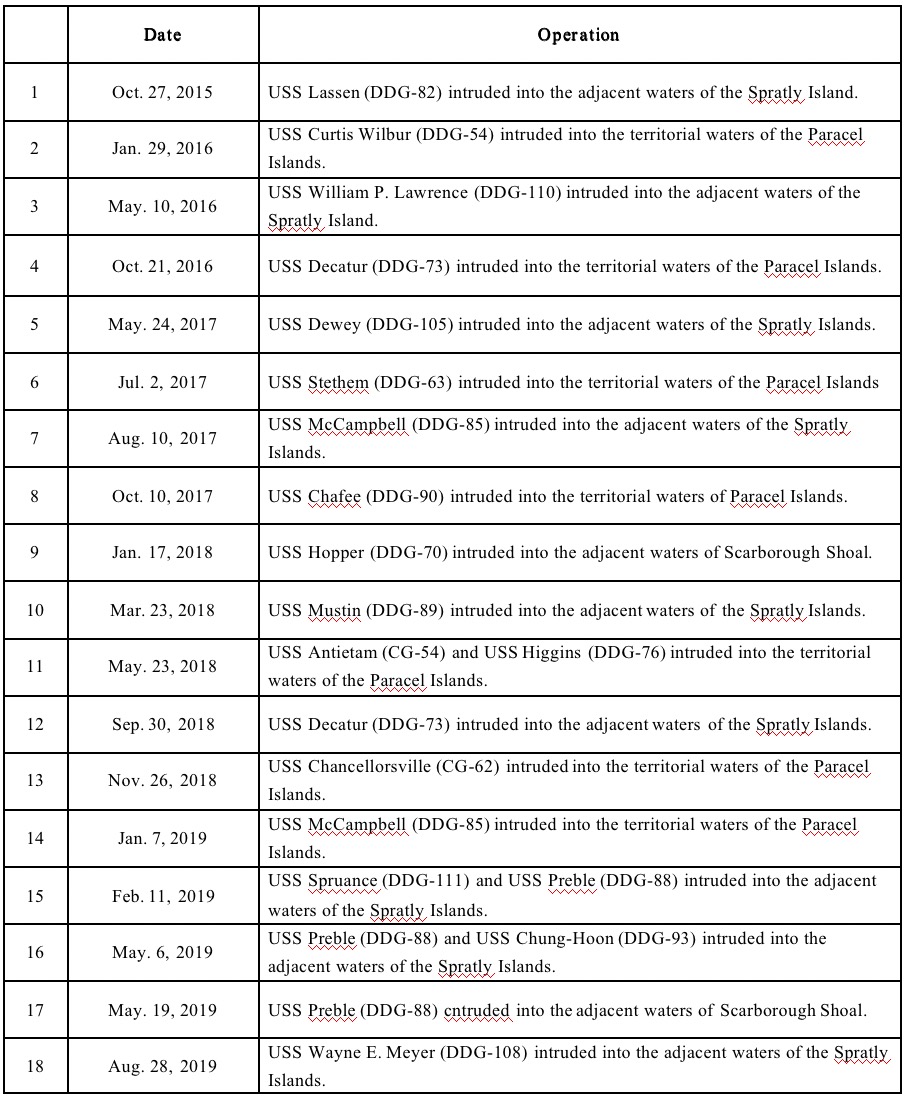

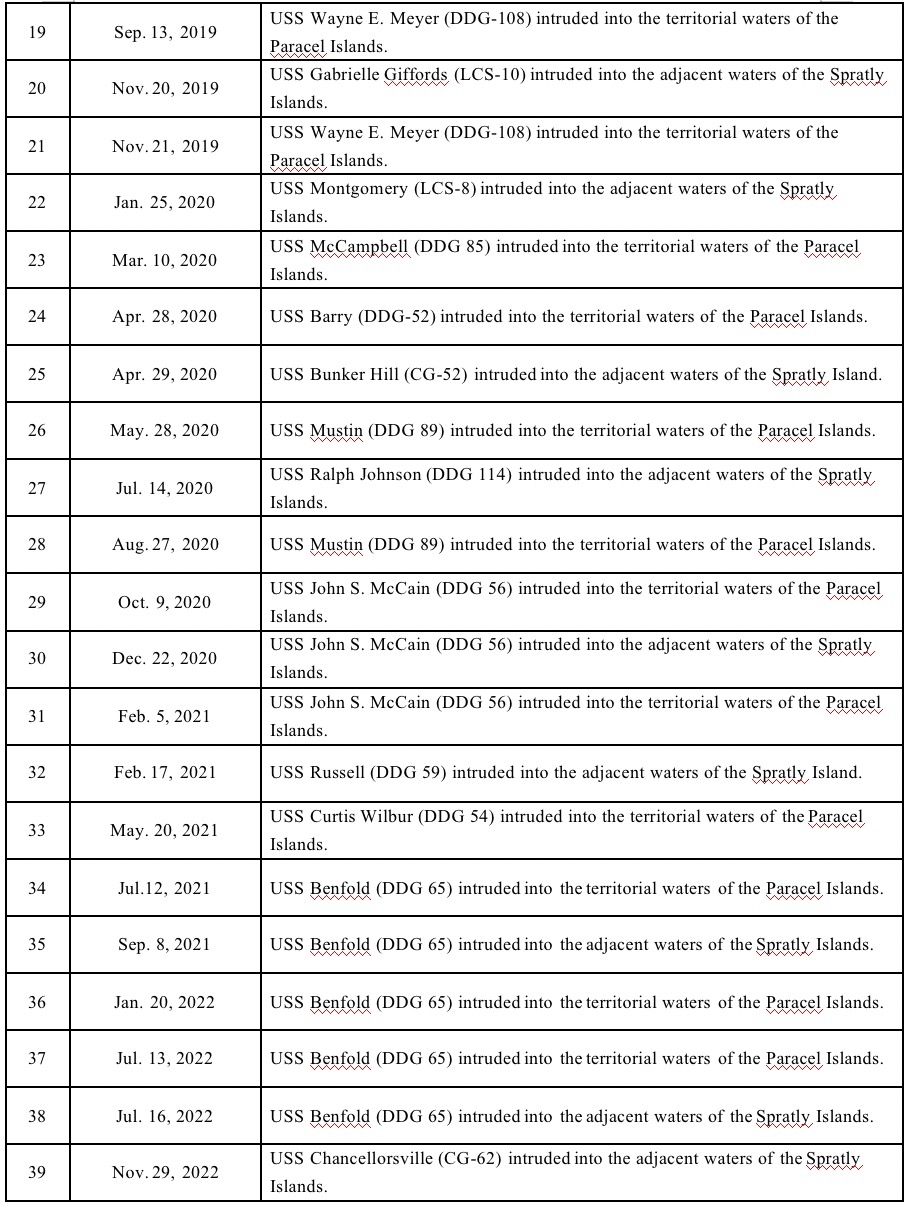

Appendix 1. US warships intruded into the territorial waters and adjacent waters of the islands and reefs occupied by China in the South China Sea

(From October 27 of 2015 to November 29 of 2022)

Appendix 2. The major agenda of China-US relations appeared on the day, within 3 days, 7 days and 15 days of US FONOPs

Note: Type 1 China’s festivals and meetings; Type 2 Important trends of the US’s China-related and maritime policies; Type 3 Important policy trends and major military operations of China concerning the US; Type 4 Regional hot spots and important international conferences; Type 5 Important bilateral interactions between China and the US