The ongoing endeavors by the Philippines to transport building materials to Second Thomas Shoal, in order to bolster the deteriorating BRP Sierra Madre and build a permanent outpost on the reef, have captured international attention. Recent revelations have surfaced that Philippine officials have earmarked funds for the construction of permanent facilities on the shoal to provide “shelter for fishermen”.[1] These developments raise at least two pivotal questions: Is the Philippines legally entitled to reinforce the dilapidated BRP Sierra Madre and erect new structures on Second Thomas Shoal? Who is attempting to unilaterally alter the status quo at Second Thomas Shoal—is it Manila or Beijing?

A key argument put forward by Manila is that the BRP Sierra Madre was grounded on the reef in 1999, before the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) was signed, and therefore could not possibly have violated the DOC. Is this really the case?

It is true that the grounding incident of 9 May 1999 does not in itself constitute a violation of the DOC, but this does not mean that subsequent actions - the transport of construction materials, the strengthening and refurbishment, and the use of various methods to attempt to "stick around" permanently at Second Thomas Shoal and the intensification of attempts to build a permanent facility at Second Thomas Shoal - do not constitute a violation of the DOC. It is clear that the Philippines has deliberately conflated these two issues.

Firstly, following the Philippine “beaching” incident, China was provided an explanation that the grounding of the vessel was attributed to mechanical failure. It was further assured by the Philippines that the BRP Sierra Madre would be promptly towed away. In a subsequent meeting in November 1999, the Chinese Ambassador to the Philippines engaged in further discussions with Secretary of Foreign Affairs Domingo Siazon and Chief of the Presidential Management Staff Leonora de Jesus to reiterate Beijing’s concerns. Despite the assurances by the Philippine authorities regarding the removal of the vessel, Manila has consistently failed to fulfill its commitments.[2]

Gregory B. Poling of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), in his book “Dangerous Ground”, provides additional corroboration, noting that “When the Chinese government demanded that the ship be removed, President Joseph Estrada (President of the Philippines from 1998-2001), feigning ignorance, promised to tow the vessel away as soon as it could be safely floated off the reef.”[3]

If the BRP Sierra Madre did indeed run aground on Second Thomas Shoal due to "mechanical failure", such a grounding would not constitute a "military occupation" of the shoal. It would simply be a maritime accident.

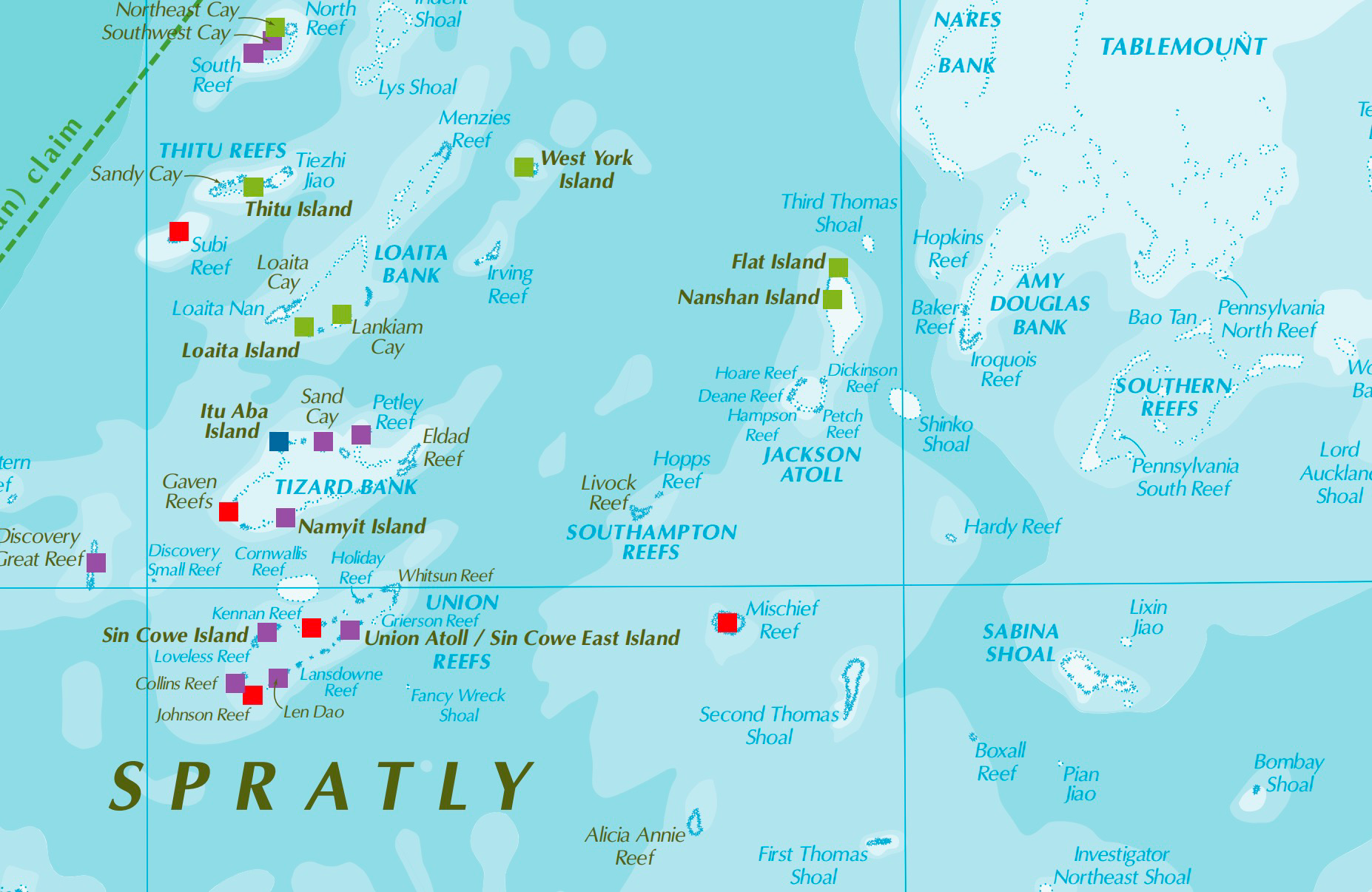

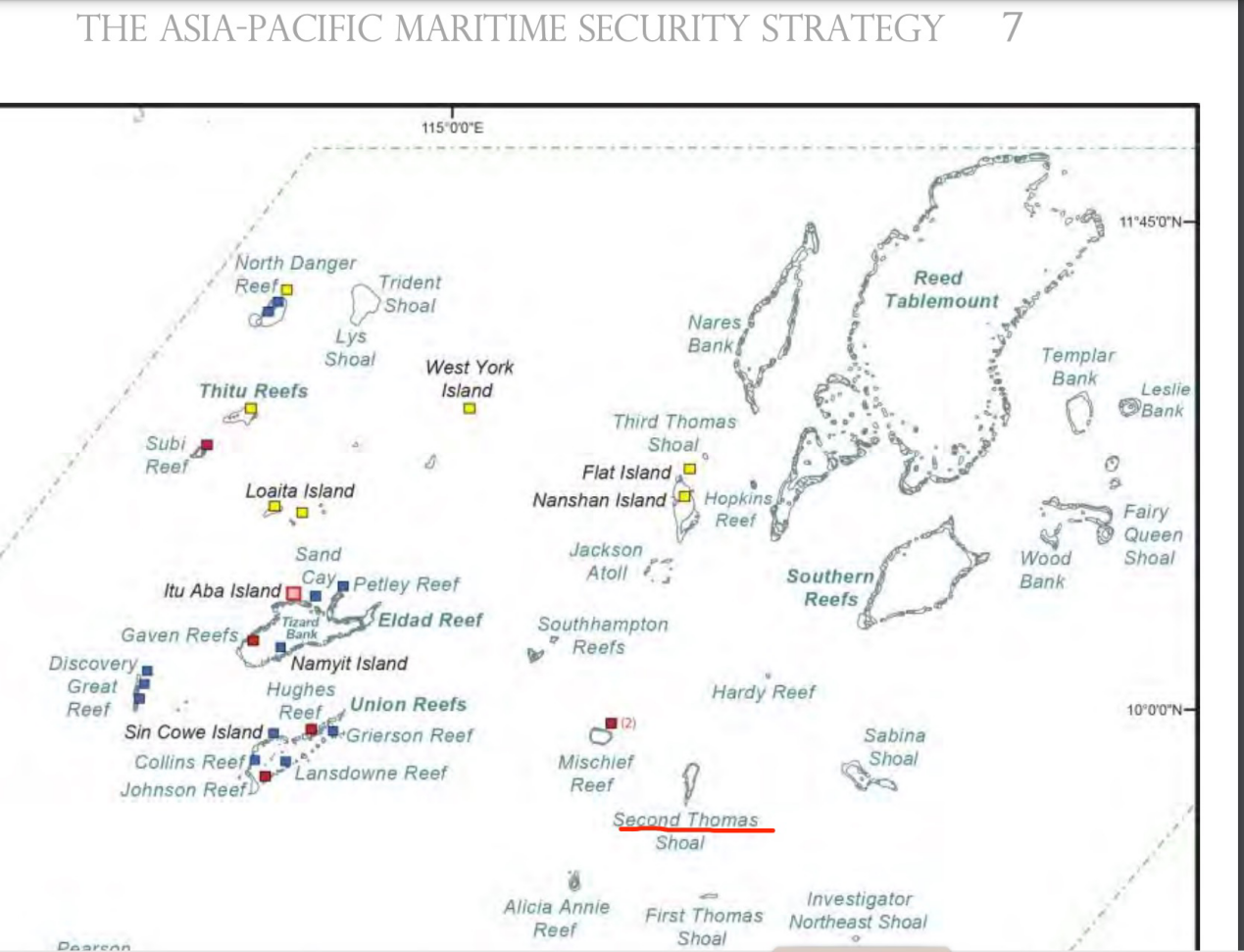

Secondly, even if the Philippines were to disguise the grounding as an "accident", but with the real intention of "occupying" Second Thomas Shoal, such an act would be temporary, not permanent, and would not be considered a formal occupation by the relevant stakeholders. The BRP Sierra Madre, a warship that has been in service since World War II, would not allow Manila to achieve a permanent and sustainable occupation of the reef due to its age and limited functionality, and also contradicts its official diplomatic stance of a maritime accident. Perhaps this is why US officials did not consider the BRP Sierra Madre a military outpost before 2016. For example, the Second Thomas Shoal was not included among the Philippines' eight military outposts in the South China Sea on a map published by the US State Department in 2010.[4] Not coincidentally, the 2015 report officially released by the US Department of Defense, titled “The Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy”, lists the Philippines' outposts at eight, it does not include Second Thomas Shoal.[5]

Source: The map above is excerpted from “Spratly Islands, Map No. 803426AI (G02284) 1-10”,US State Department, 2010.

Source: The map above is excerpted from “The Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy: Achieving US National Security Objectives in a Changing Environment”, US Department of Defense, 2015

Third, perhaps in a bid to seek protection under the US-Philippines Mutual Defense Treaty, the Philippines has consistently emphasized that the BRP Sierra Madre is an active naval vessel of the Philippine Navy and not a permanent installation at Second Thomas Shoal. So, what exactly is the nature of the BRP Sierra Madre - an active warship, a wreck or a permanent outpost? From a legal perspective, it seems implausible for Manila to claim that the BRP Sierra Madre is both an active warship and a permanent outpost.

It is obvious that the Philippines' positioning of the BRP Sierra Madre at Second Thomas Shoal is accidental and temporary. Neither its diplomatic démarches nor its grounding constitute a formal occupation of Second Thomas Shoal, which has also been the subject of continuous and unwavering protests from China since its inception.

Fourth, after signing the DOC on 4 November 2002, the Philippines repeatedly promised not to build permanent structures or even transport construction materials to Second Thomas Shoal. For example, in September 2003, acting Philippine Foreign Secretary Franklin Ebdalin stated that the Philippines had no intention of building facilities on Second Thomas Shoal, noting that the country was a signatory to the Declaration and did not want to be the first to violate it.[6] On 19 June 2013, when Philippine Defense Secretary Voltaire Gazmin discussed Second Thomas Shoal issues with Chinese Ambassador to the Philippines Ma Keqing, Ma raised concerns about Philippine plans to build structures on the reef, in response Gazmin assured Ma that there were no such plans.[7]

Fifthly, despite various flip-flops and Philippines’ general failure to acknowledge or adhere to these so-called “gentlemen’s agreements,” it is indubitable that the Philippines’ continued reinforcement, and attempts to establish permanent structures on the shoal contravene Article 5 of the DOC. This key provision pledges all parties “to exercise self-restraint in the conduct of activities that would complicate or escalate disputes and affect peace and stability including, among others, refraining from action of inhabiting on the presently uninhabited islands, reefs, shoals, cays, and other features.” This has been a widely followed commitment since the conclusion of the DOC in 2002.

In conclusion, the grounding of the BRP Sierra Madre was publically acknowledged as accidental and temporary in nature. Since 2010, the Philippines has attempted to reinforce and refurbish the BRP Sierra Madre, and has consistently caused incidents in violation of the DOC's obligations for all parties to exercise restraint and refrain from occupying uninhabited features. It is attempting to unilaterally alter the status quo at Second Thomas Shoal. Manila claim that "Philippines has been in long, continuous, peaceful, uninterrupted, and effective possession of the shoal under international law" is a complete falsehood.[8] At present, there are still over a hundred uninhabited and features in the Spratly Islands. If the Philippines flagrantly violates this commitment, it could trigger a new wave of occupation activities, exacerbate tensions and chaos in the South China Sea, and significantly impede negotiations for a code of conduct in the region.