In the Chairman’s Statement of the 26th ASEAN-China Summit, issued in September 2023, it was stated that both sides recognized “the need to maximize the potential of blue economy as the new engine of growth to promote economic growth, social inclusion and livelihoods, and environmental sustainability” and that both sides also “agreed to continue discussion on exploring a partnership on blue economy between ASEAN and China as envisaged in the ASEAN-China Strategic Partnership Vision 2030 to promote marine sustainable development and create new highlights in ASEAN-China cooperation.”

Blue economy partnership has often been included in various statements between China and ASEAN in recent years, underscoring the huge potentials of marine economic cooperation for both sides. In particular in the context of growing geopolitical uncertainties and tensions, the blue economy partnership is often touted by the Chinese government and scholars as one way to reduce tensions, generate positive momentums, and create a stronger foundation for regional cooperation and mutual trust between China and ASEAN.

The blue economy covers a wide scope of economic activities, including fisheries and aquaculture, coastal and marine tourism, extractive industries (mainly oil and gas), maritime transport, logistics, shipping, renewable ocean energy, marine biotechnology and bioprospecting, desalination for freshwater generation, ocean plastic and waste disposal management, among others. Within the blue economy, fishery and aquaculture plays a significant role in the food security interests of Malaysia and China.

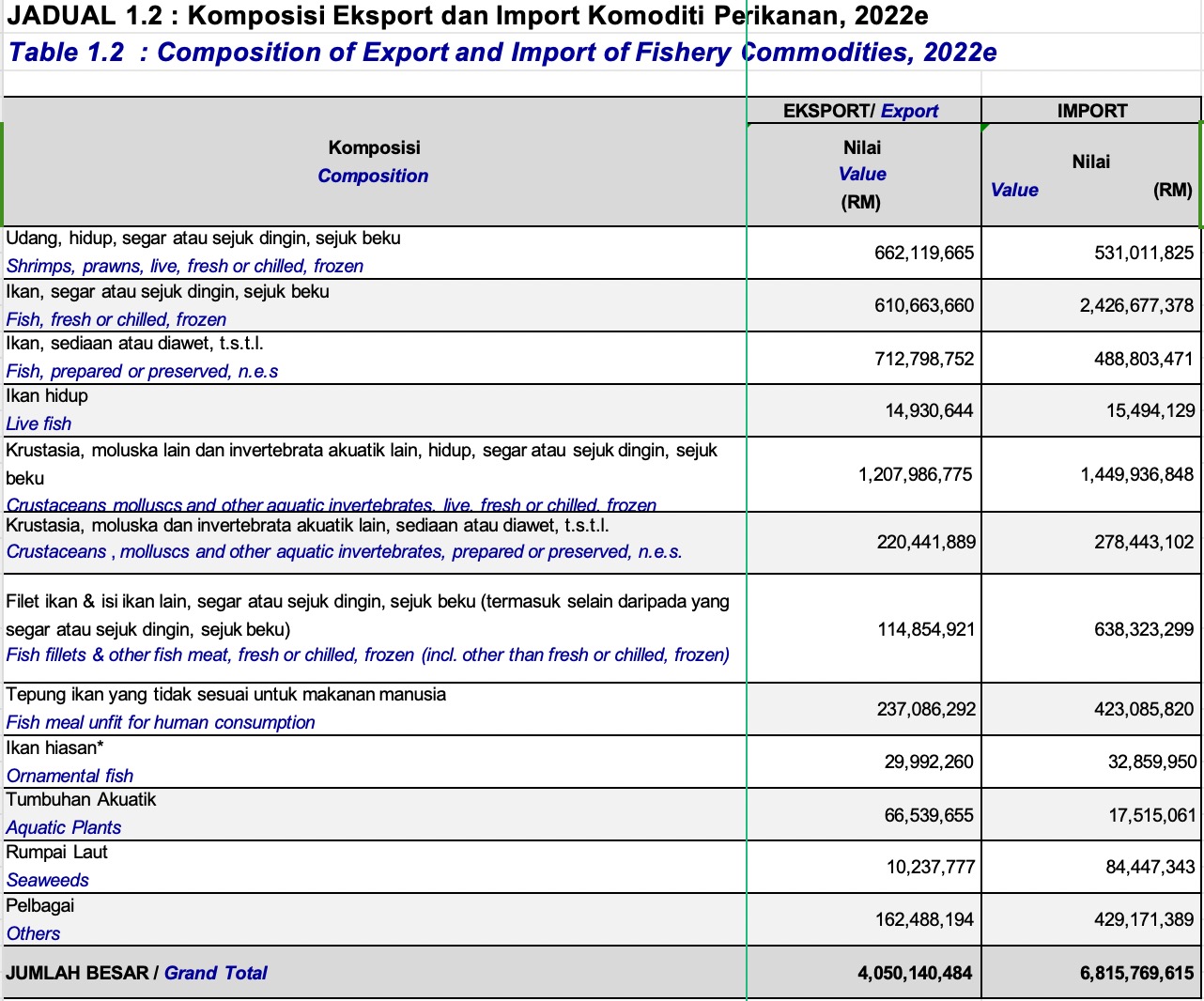

However, the fishery and aquaculture sector in Malaysia is not particularly strong. Fish contributes 44% of the total animal-sourced protein intake of Malaysians, which is above world’s average, but the country’s fishery and aquaculture sector has not been able to provide for its own citizens’ needs adequately. As noted in the Position Paper on the Blue Economy, a report released in early 2023 by the Akademi Sains Malaysia, a premier scientific expert organization in Malaysia, in 2020, Malaysia’s total fishery production amounted to 1.79 million tons, comprising 1.38 million tons from capture fisheries and 0.4 million tons from aquaculture (excluding seaweeds). Despite growing needs, its fisheries production from both capture fisheries and aquaculture actually went down from 2016 to 2020. Malaysia also remains a net importer of fisheries products.

Furthermore, notwithstanding the declining and over-exploited fish-stock in Malaysia’s marine areas, Malaysia has not really strengthened its aquaculture sector, especially when many of its neighbors are already significantly investing in aquaculture, in view of the growing awareness of the strategic importance of food security. The Position Paper report (pages 38-39) lists eight shortcomings of Malaysia’s fisheries and aquaculture industries, including the lack of scientific assessment of fish stocks, the lack of application of new technologies, high fuel cost, the lack of local processing industries, inadequate fisheries management policy measures, ineffective governance across government and fishing communities, multiple administrative jurisdictions, the lack of long-term objectives, and the lack of political consensus to tackle these issues.

China, on the other hand, has grown its fishery and aquaculture sector so successfully that it has become the biggest fish producer in the world, accounting for 40% of world supply in 2021. Aquaculture has exceeded more than 50% of total fishery production since 1990. By 2021, aquaculture supply is 5.5 times the captured supply. This rapid expansion was achieved by a series of state intervention, including a “zero-growth” for marine fishing, leaving aquaculture as the main source of fishery development. Research, technological development and information dissemination in for example, breeding technologies, high quality, and artificially formulated feed as well as fish health management also contributed to the rapid growth of this sector.

Malaysia has a lot to learn from China’s extensive and long experience in aquaculture development, leading to potential areas of economic cooperation. In general, Malaysia tends to depend on Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) for economic cooperation, as inviting FDI brings capital and employment to Malaysia. Export-oriented FDI will meet China’s increasing domestic demand for fish from the expanding middle class, when the farmed seafood is exported to China. But, seeking FDI from China in this sector may not be the best strategy as China is more inclined towards mergers and acquisitions rather than greenfield investments in this sector. This adds little value to the sector, while it can be a threat to local smallholders and the environment such as nutrient and effluent build up and environmental degradation. A better form of cooperation is technical cooperation and training, especially in mitigating the negative enviromental impact. This will enhance sustainable aquaculture development so that the farmed fish/seafood in Malaysia are cultivated in a sustainable manner for domestic consumption and exports, including to China.

Instead FDI should be invited for the fish/seafood processing industry in Malaysia, to add value to the locally farmed fish and seafood. The processed output can be frozen, canned or in the form of surimni and surimini products. Although Chinese consumers prefer to consume live seafood, there is a growing demand for convenience food, such as easy or ready to cook processed food as these can meet the current busy lifesyles of the young working population, with higher disposable income, so that there is potential for domestic demand and export to other countries in the region.

More importantly, Malaysia needs to learn from China’s expensive lessons in acquaculture development, as it also had an adverse impact on wild catch because they are used to feed farmed fish, leading to strained fisheries resources. Globally, however, aquaculture is found to be a have a positive net production of fish protein, since half a metric ton of wild whole fish is used to produce one metric ton of farmed seafood. Nevertheless, a two pronged strategy for cooperation is needed for sustainable fishery development. The first is to support China’s development of alternative fish food, and compound feed, or feed that is mixed with other ingredients harvested from the land. Second is to work together on marine protection to overcome common challenges such as illegal fishing and habitat destruction. This will help to shape a science-based cooperation that can help to preserve the marine resources for both countries.

The above suggested forms of cooperation will not yield any substantive impact if it remains at the level of intergovernmental discussion and dialogue alone. Instead, concrete projects will have to address the needs, demands, and comparative strengths of the partners. Careful evaluation of the feasibility and durability, including costs, markets, environmental considerations, and other aspects are also very much required. This includes investigating why previous attempts at fishery cooperation have not worked out. For example, in 2017, it was announced that China was planning to invest in the development of an integrated fishery terminal for landing and processing tuna fish in the state of Kedah in Malaysia. However, the project did not materialize as planned. Learning from previous investment failures will help new investors to propose better projects for both countries. Engaging the private players in this industry in the formulation of concrete proposals such as through organized meetings with relevant associations in the fishery and aquaculture sectors of Malaysia and China is also critical for moving towards more substantive cooperation efforts.