Routine U.S. military operations in the South China Sea do not typically make headline news. Since the end of the Second World War, the United States has executed a variety of complex military operations in the South China Sea, which can generally be classified into six categories: declaratory actions, presence operations, military reconnaissance and intelligence collection, drills and training, battlefield construction and validation of operational concepts, and deterrent action. The well-known freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) are among those declaratory actions. Besides, there were also various highly intensive operations in wartime.

From 2009 onwards, the U.S. military has substantially increased the frequency, intensity and pertinence of its operations in the South China Sea. According to Automatic Identification System (AIS), Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) and other open resource, over the past decade, US surface ship presence has increased by 60 percent to around 1,000 ship days per year. The military aircraft sorties have been up to over 1,500 all year round, which is almost twice as many as that in 2009. Every day, there are three to five military aircraft operating in the South China Sea, most of them undertaking reconnaissance.

That being said, the recent U.S. military operations in the northeast of the South China Sea seemed to be unusual.

New Developments

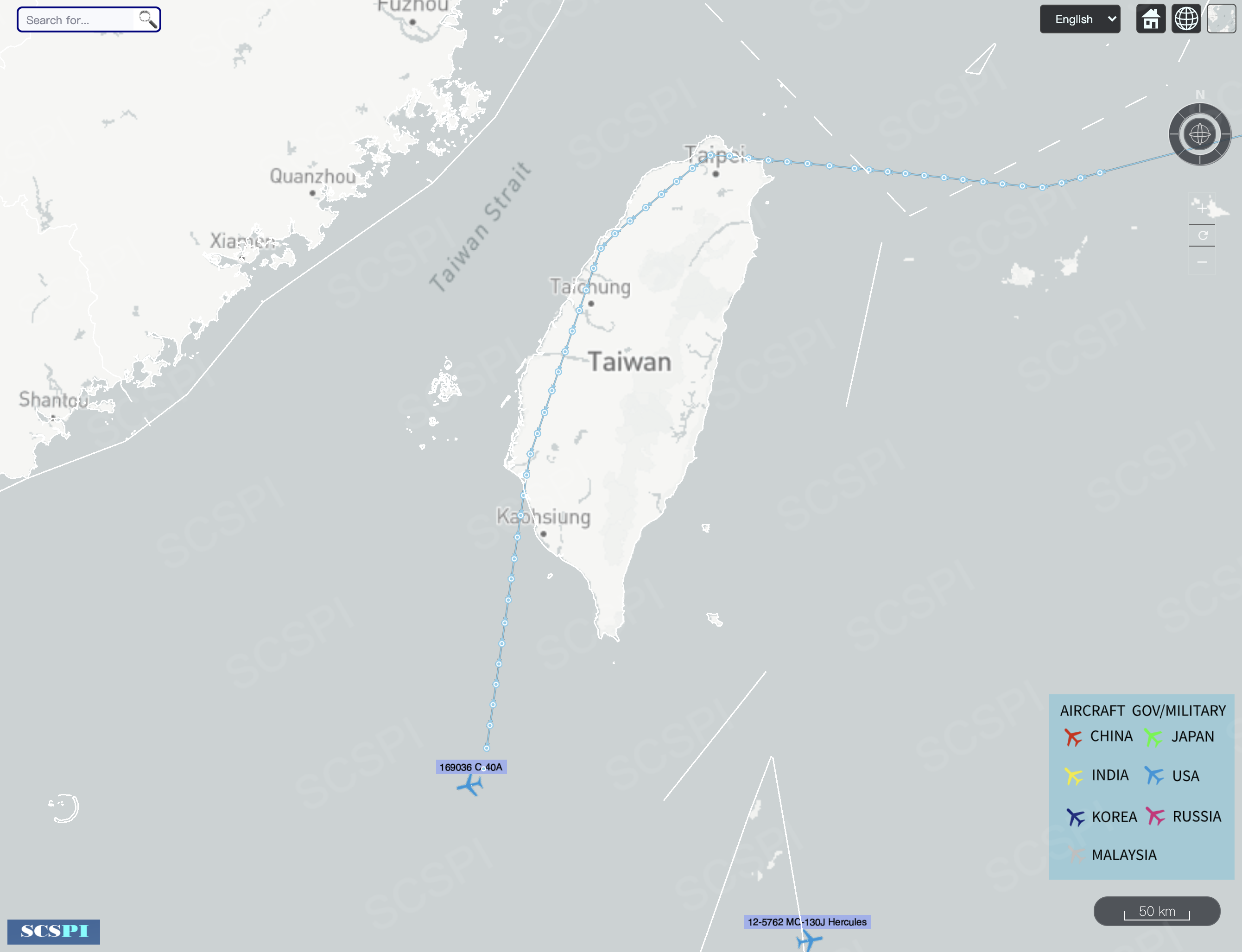

Recently, Taiwan-based media and some international media outlets have highlighted up the frequent entrance of fighter jets from the Chinese mainland into the southwest air defense identification zone (ADIZ) of Taiwan. In fact, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the U.S. military and Taiwanese forces have all stepped up vigilance and patrols off the southwest coast of Taiwan since a U.S. Navy C-40A transport aircraft flew over Taiwan on June 9.

Flying over of USN C-40A, June 9

According to Taiwanese reports, military aircraft of the PLA, including J-10, Su-30, Yun-8, and J-11, have “crossed into” the southwest of Taiwan’s Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) at least eight times during June. However, this is because US reconnaissance aircraft are frequently spotted in that airspace. P-8A, EP-3E, RC-135U, P-3C and even Global Hawk drones were sent to the area with over 30 aircraft sorties in the last 10 days. An average of 3 sorties per day, sometimes like June 24, even 4 sorties of reconnaissance aircraft including 2 P-8As, 1 P-3C and 1 RC-135W, plus 1 KC-135 refueling tanker, were conducted. Similarly, on June 29, 2 P-8As, 1 EP-3E, 1 RC-135W and 1 KC-135 undertook sorties.

The US Military aircraft activity in the South China Sea, June 24

Unlike previous daily aerial reconnaissance and patrols, the U.S. reconnaissance aircraft active in the South China Sea lately were mostly found off the coast of Guangdong, and near the Bashi Channel, in the northeast of the South China Sea.

Intentions and Purposes

In general, the U.S. military basically maintains 3 reconnaissance sorties a day in the South China Sea, which is a significant improvement over the previous average of 2 sorties. Both the US Navy (USN) and US Air Force (USAF) reconnaissance aircraft have participated in the activities, which are very extensive in type and scope. Specifically:

Anti-Submarine Operations

As the key patrol and reconnaissance aircraft of the US Navy, the P-8A is used for many purposes, including maritime patrol, reconnaissance and anti-submarine warfare (ASW). With a range of over 2,000 nautical miles, it routinely operates over the South China Sea. Still, it is rare to see two P-8As deployed to the east of Bashi Channel in relays within a day.

These deployments and operations are probably arranged to protect the three Carrier Strike Groups (CSGs) operating in the Philippine Sea against any potential adverse impact of submarines transiting the Bashi Channel on US aircraft carriers. Recently, the USS Nimitz strike groups have just conducted two Western Pacific dual-carrier exercises with USS Theodore Roosevelt strike groups and USS Ronald Reagan strike groups successively in a week.

USNI News Fleet and Marine Tracker: June 29, 2020

Submarine is usually regarded as the main threat of CSGs. It is embarrassing that there is some unknown submarine nearby when CSGs flex their muscle. For this reason, it is estimated that the U.S. military will enhance anti-submarine deployments and operations near the Bashi Channel for some time to come, and reconnaissance aircraft like P-8A are bound to operate under a hectic schedule.

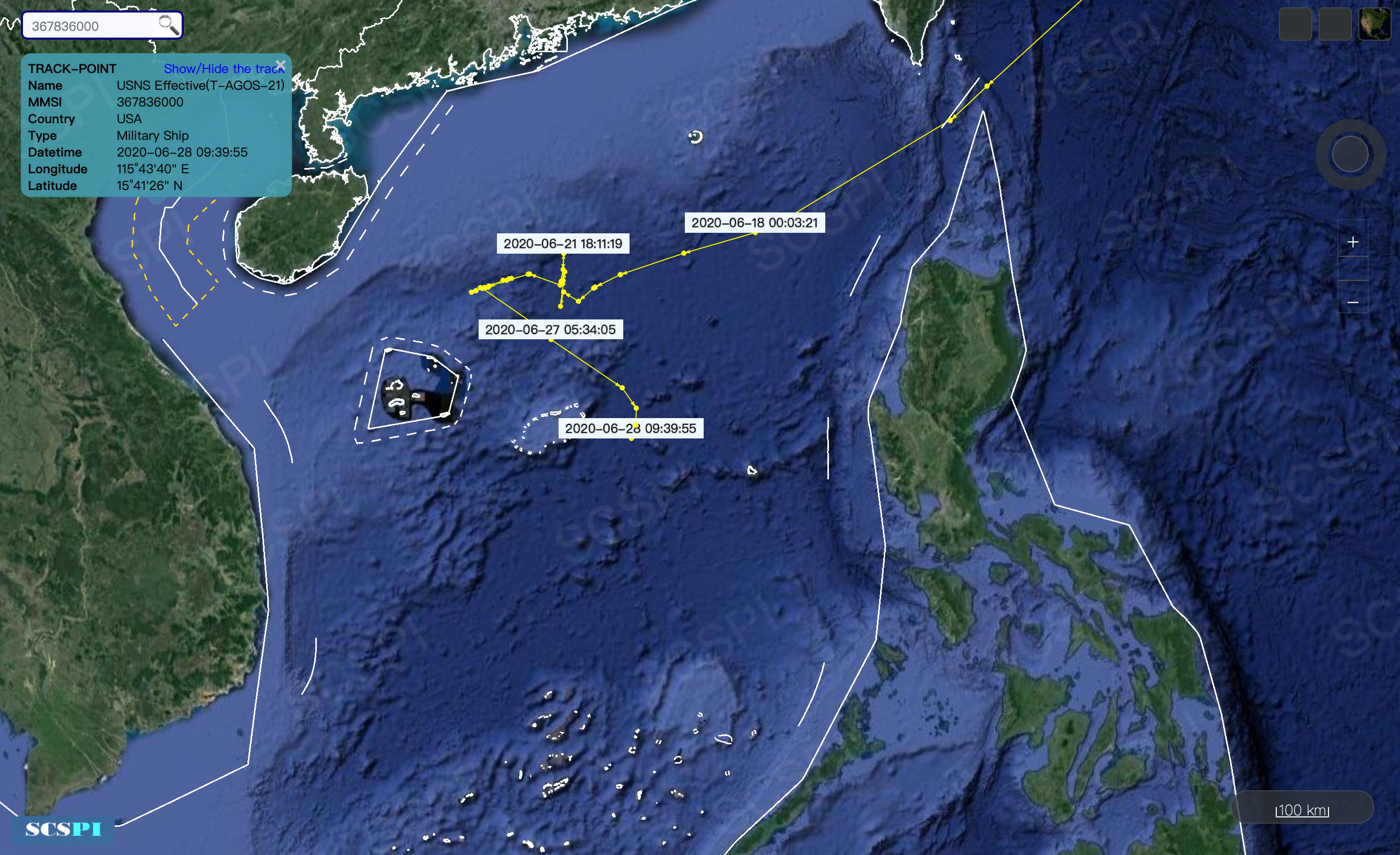

In addition to aerial reconnaissance, the US Navy has also maintained a constant presence of surveillance ship in nearby waters. The Victorious-class USNS Effective (T-AGOS 21) was deployed to the area two weeks ago. It has already reached the waters between Hainan Island and the Paracel Islands by now. Usually, it would drop several unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs).

Tracks of USNS Effective, June 16 - 30

Battlefield Construction

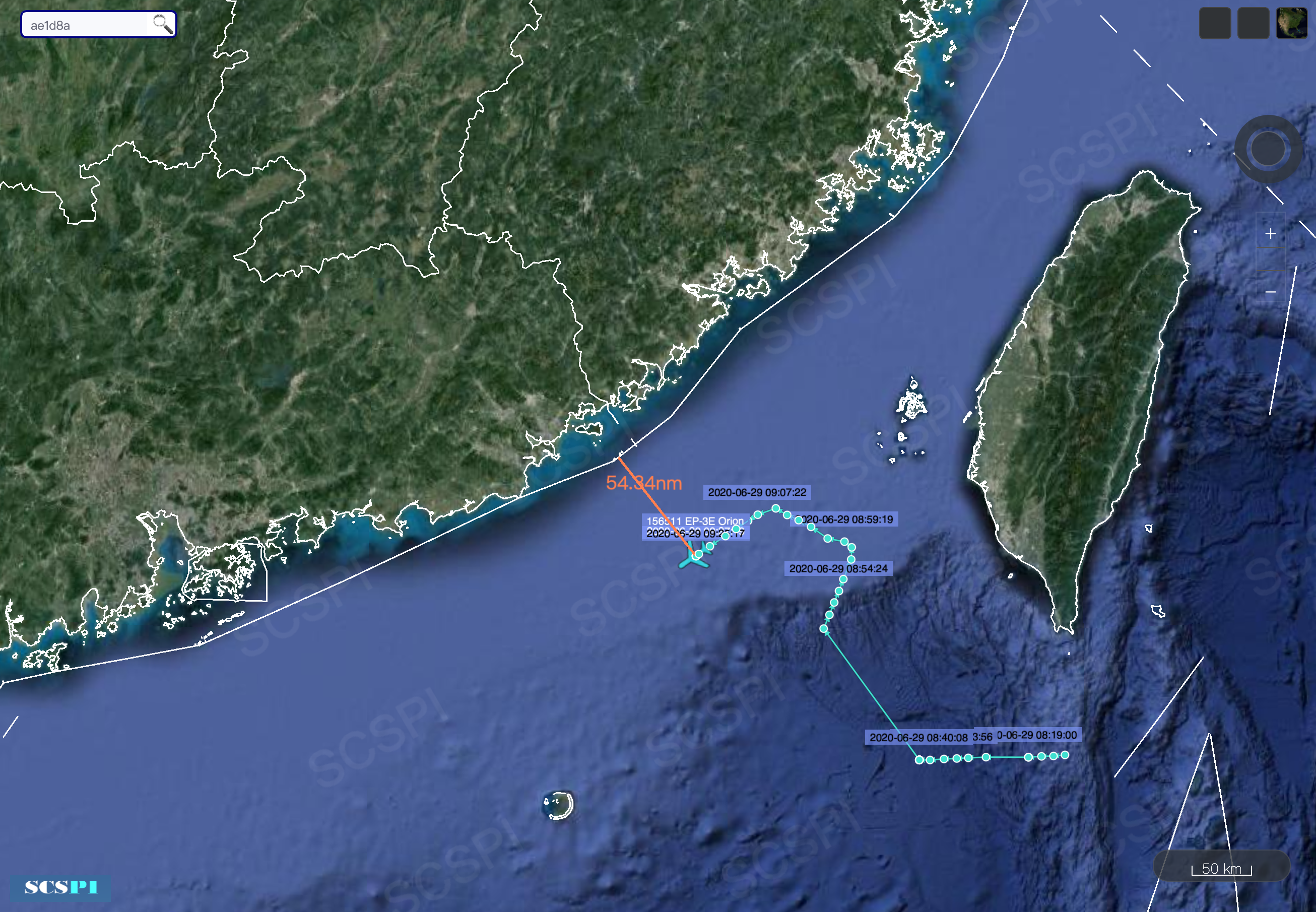

In the backdrop of power competition and “Return to Sea Control,” all the U.S. military services are actively promoting a series of operational concepts against China, such as the concept of “Distributed Maritime Operations” by the US Navy, “Multi-Domain Operations” by the US Army, and the “Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations” (EABO) by the US Marine Corps. These concepts mostly assume the South China Sea as the battlefield, and construct strategies and war-game simulation under that premise. In recent days, U.S. reconnaissance aircraft have been approaching the offshore airspace over Guangdong, which is to increase their collection of electronic signals from Mainland China, rather than focusing on surface and underwater targets in the South China Sea. The RC-135 series are strategic reconnaissance aircraft of the USAF, mainly conducting close reconnaissance over the coast of the target country. Among them, there are only two RC-135Us, whose main task is to collect various electromagnetic waves, especially frequency-hopping. The RC-135W is mainly used for electronic reconnaissance and monitoring, by listening to the electronic signals of radar and communication equipment of opponent to obtain electronic intelligence data. Undoubtedly, the EP-3E and RC-135 series are important tools for US military to facilitate the battlefield construction.

Close reconnaissance of USN EP-3E (ICAO: AE1D8A) off the coast of Guangdong and Taiwan, June 29

Close Reconnaissance of USAF RC-135U (ICAO: AE01D5) off the coast of Guangdong and Taiwan, June 29

Regular Patrols

Due to the complete flight path information not yet being available from open sources such as ADS-B, it is impossible to determine the detailed scope of its reconnaissance and patrol. Usually, the reconnaissance scope should not be limited to the northeast part of, but the whole South China Sea. These reconnaissance aircraft have long range and operational persistence. The use of refueling tankers almost every day means that those reconnaissance aircraft are needed either for higher intensity or wider range.

Even when the South China Sea is calm, the U.S. military is also operating two sorties of reconnaissance aircraft every day for routine patrolling.

Effects and Influence

ASW is a challenge for the entire world, including the U.S. military. Unlike other channels in the Western Pacific, the Bashi Channel connects the Philippine Sea with the South China Sea with a deep canyon and separates Taiwan from the Batan Islands, which makes it a busy waterway of strategic importance in the Western Pacific. The channel enjoys an average width of 185km and a maximum depth of 5,126m, with the depth of the waterway ranging from 2,000 to 5,000 meters. Even though it is a strait, it will be like trying to find a needle in a haystack to detect it once a submarine operates underwater here.

Therefore, ASW is extremely challenging in this environment, sometimes just for self-reassurance. Even if the US military learns from other channels that there is submarine activity underwater, the depth and complex hydrological environment would make it difficult to detect the precise location. It is likely that the presence of a USN CSG will attract the attention of other states’ underwater forces, and the US military still has to deal with many uncertainties from the environments of the Philippine Sea and the South China Sea. Nowadays, absolute security has passed away, especially in the underwater environment.

Of course, the execution power of the U.S. military system is admirable. Aerial, surface and underwater reconnaissance forces will increase peripheral vigilance and patrols once any major operation commences, swiftly mobilizing various forces across a wide range. When it comes to anti-submarine capabilities, the US military is unarguably the strongest on earth, both in terms of its single platforms like the P-8A and its systematic capabilities. Furthermore, the US military’s bottom-line thinking of “always preparing for the worst” is inspiring as well for troops across the world. It is worth to mention that the US keeps an eye on the dynamics of its opponents in the South China Sea even during military exercises in the Philippine Sea. This is exactly what it means by saying “always keeping readiness as if it were war.”

Close reconnaissance has always been a contentious issue between China and the United States with ongoing frictions. The US insists on expanding the connotation of the freedom of navigation and overflight and attempts to generalize the provision of Article 58 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (hereinafter referred to as the UNCLOS). In particular, it tries to categorize close reconnaissance and survey activities as one of the “other internationally lawful uses of the sea.” Broadly speaking, as a traditional maritime power, the US always expresses reservations about the rules for exercising any restrictions on military operations at sea. The US Truman Proclamation of 1945 was the first to propose the concept of the continental shelf system, which highlights economic resources of littoral states, but has opposed restrictions on military operations in exclusive economic zones (EEZ) for all these years. To support this concept, the US even coined the term “international waters”, which extends the freedom of the high sea to waters 12 nautical miles away from a littoral state’s baseline. Given that there are only a few provisions on military operations in UNCLOS, China has not actually contended much with the US in the legal sense, though China obviously disagrees with the so-called “international waters” and absolute freedom of military operations championed by the US.

In spite of that, China has to track and guard against the close reconnaissance of the US military because it is in close proximity to China and thus gravely endangers China’s security. China’s response is consistent with international practice. Many U.S. officials used to say that they welcome Chinese warships and military aircraft to conduct operations off the coast of the United States. Whilst if China actually did, the US military would certainly respond to the move with more drastic and intensified actions. Chinese warships only occasionally sail to the EEZs of Guam and Australia, which has sparked an intense response and much attention from the US and Australia, labeling it as “China Threat”. If the US were in the China’s position, the US should understand China’s concerns for security.

In an era of great power competition, the US military targets China strategically, tactically and operationally, and continuously plays up the situation. However, it should have realized that these actions will definitely invite a response from China, and that the “security dilemma” will only spiral up. China has neither the intention nor capacity to chase the US military out of the South China Sea; the US cannot maintain its hegemony in the waters either. As a result, it is not impossible to see the peaceful co-existence of forces from both sides. Yet, everything eventually boils down to one fact: if one seeks absolute security and dominance, then the other would never give in.

Both the U.S. government and its military should learn how to treat China’s regime and the PLA as their equals or try to do so at least in the South China Sea and Western Pacific. Consider if China sent thousands of reconnaissance aircraft sorties to the East and West coasts of the United States every year and accused the US military of managing the situation unprofessionally, how would the White House, the Pentagon and the U.S public react? Actually, China doesn’t want much, but just equality.

It is common knowledge that the military is, of course, prepared for war and other worst-case scenario. However, the regional situation will only be backed into a corner if the U.S. military keeps giving undue prominence to great power competition in the South China Sea.