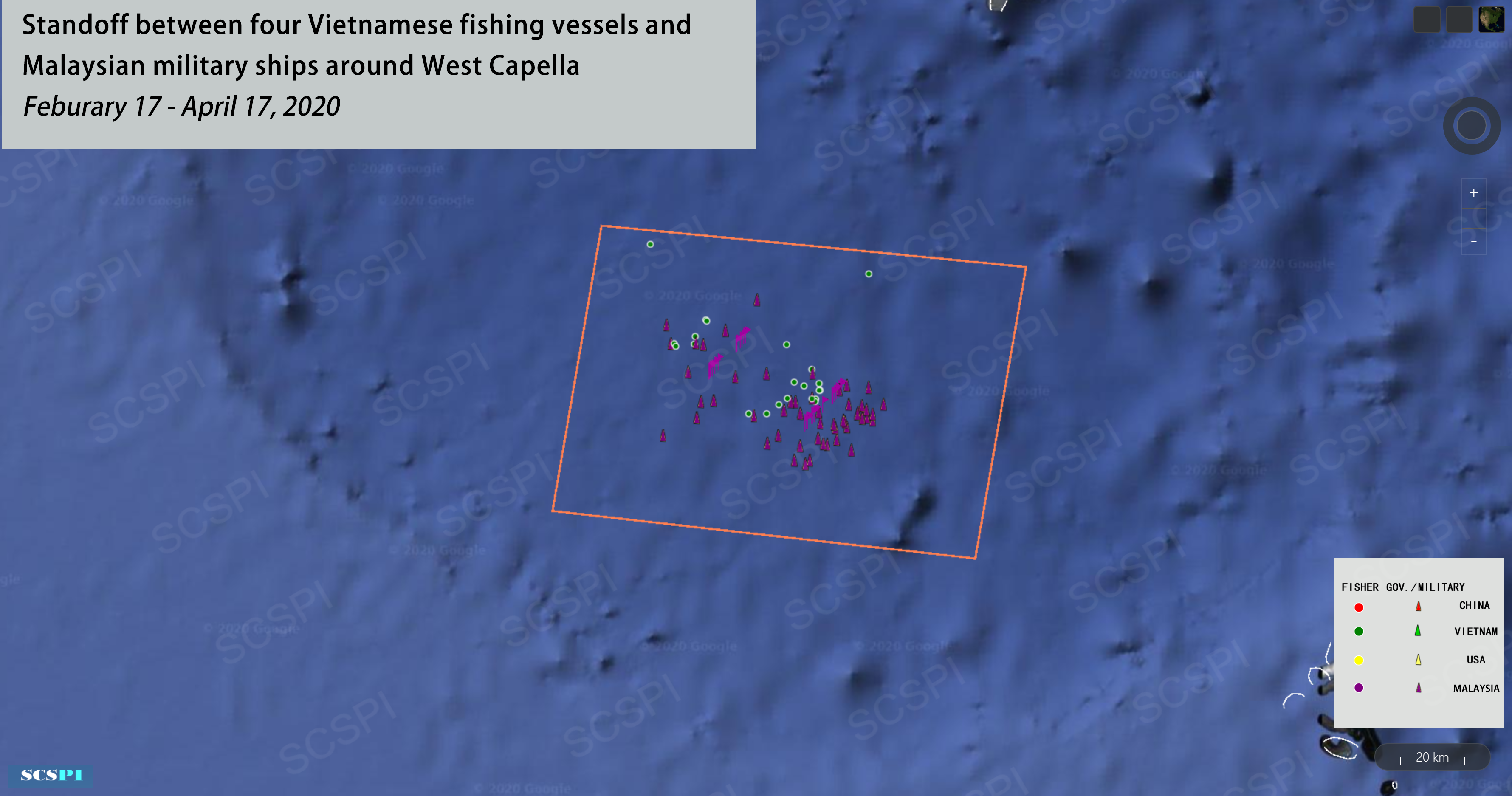

In recent months, amidst the fight against the COVID-19 outbreak, tensions in the South China Sea continued to draw attentions. On April 17, Reuters reported a “standoff” between the West Capella, an oil drilling ship contracted by Malaysian national oil company Petronas, and Haiyang Dizhi 8, a Chinese scientific survey ship. Also mentioned in the report, but which has been ignored or downplayed by most western media and analysts, was that some Vietnamese ships were also tagging the West Capella, since the area where the West Capella was operating is also claimed by Vietnam.

Vietnam and Malaysia had been locked in a stand-off before Haiyang Dizhi 8 arrived

Nevertheless, the narrative of Malaysia-China “standoff” quickly took shape. On April 20 the U.S. Navy dispatched two warships, joined by an Australian Navy vessel, to the area, in an apparent move to bolster Malaysia. Subsequently, the US mustered a continuous, robust military presence in the area for weeks, demonstrating to China that despite the U.S. Navy being impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, it could still deploy an effective check against China. The deployment was seen by many western and Southeast Asian security analysts as demonstrating strong US’s commitment to the international law and an assuring backing up of “allies and partners” in Southeast Asia. The whole episode ended after the West Capella left the area after completing its work on May 12, followed by Haiyang Dizhi 8, which left three days later.

U.S. Navy and Australian Navy took joint operations near West Capella, 20 April 2020

Malaysia’s reaction to the dispatching of the uninvited warships by the US, however, was ambivalent at least, and unwelcoming at most. On April 22, an unnamed governmental source from Malaysia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs first denied that there was a “standoff” between Malaysia and China. Shortly after, Malaysia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hishammuddin Hussein, issued a statement. It stated that “we [Malaysia] must avoid unintended, accidental incidents in these waters. While international law guarantees the freedom of navigation, the presence of warships and vessels in the South China Sea has the potential to increase tensions that in turn may result in miscalculations which may affect peace, security and stability in the region.” The Statement also reiterated Malaysia’s stance that “any dispute should be resolved amicably through peaceful means, diplomacy and mutual trust by all the concerned parties.” It stressed that Malaysia has “open and continuous communication with all relevant parties, including the People’s Republic of China and the United States of America.” It was a clear signal that Malaysia intended to defuse and de-escalate the situation.

Malaysian Foreign Affairs Ministry denied "stand-off"

It is worth noting here that, without naming names, “warships” and “vessels” apparently referred to both U.S. Navy warships and China Coast Guard vessels. By touching on the escalatory implications of the presence of these ships, the Statement reminded of the message articulated by the previous Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammad, about “warship attracting warship.” The pointed mentioning of both the US and China at the end of the Statement reinforced Malaysia’s longstanding stance of neutrality and non-alignment. So far, there are not many signs that the newly formed Perikatan Nasional government, which came into power under a highly controversial circumstance in early March, will deviate from the past traditions of Malaysia’s foreign policy.

Hishammudin’s statement certainly did not impress certain quarters. Commenting on this episode, Euan Graham, a maritime security expert based in Singapore’s Institute of International and Strategic Studies (IISS), noted that Malaysia’s apparently unappreciative message to the US “did not go down well in Washington.” However, he also took note that some officers within the Royal Malaysian Navy would prefer a strengthening of US-Malaysia defense partnership and by implications, a greater resolve from the civilian leadership to act tough on China. Similarly, Blake Herzinger, another security analyst, suggested that US should learn from this episode how to communicate and coordinate better with Malaysia, in particular the professional military establishment.

Indeed Chinese assertive actions in the South China Sea have generated strong resentments among Malaysia’s defense establishment and strategic studies circle (and even in the wider Malaysian public opinion). Although China’s analysts and officials see China’s actions as reactive to what they understand as Malaysia’s unilateral drilling operations in a disputed area, most of their Malaysian counterparts however would question the legitimacy of China’s claims and see China’s actions as intruding into Malaysian maritime zones. Unsurprisingly, many of them do prefer to see a closer military partnership between the US and Malaysia to deter China.

But Malaysian civilian political leadership, across different administrations, have consistently displayed far more cautiousness. They continue to downplay Malaysia’s differences with China and are wary to draw Malaysia strategically too close to the US. A popular conventional explanation is that China’s economic hold on Malaysia has greatly dis-incentivized Malaysian leaders to speak louder and made them “tepid.” Another view is that Malaysia’s muted response, based on “selective alignment,” has been exactly working fine as it quietly allows stronger response to China’s assertiveness from more powerful countries while avoiding confrontation with China on its own.

Beyond these explanations, however, is the real and acute anxiety of being entrapped in a New Cold War as the US-China relations became tenser by the day. While Malaysia has its own unhappiness with China in the South China Sea, by and large it does not see China as an existential threat, systemic adversary, ideological rival, revisionist hegemon, or any of similar sorts. Irrespective of political background, Malaysia’s political leaders generally judge that it is not in the interest of Malaysia to be enlisted into an epic New Cold War between “free and repressive visions of the world order.” A mishandling of the dispute will force Malaysia into a bigger fight with China that does not necessarily serve Malaysia’s interests.

Hence, in the South China Sea, while Malaysia is worried about China’s assertiveness, it is also equally worried about “[t]he growing rivalry and action-reaction between powerful nations” that “have raised the risk of regional polarization,” as the newly released Malaysia’s Defense White Paper put it (Chapter 2, Paragraph 9). To disentangle Malaysia’s specific dispute with China from the generalized, broader geopolitical struggle emerging on the horizon, a calm and cautious handling of the issue is needed over quick judgments and emotional reactions.

Viewed in this light, Hishammudin’s statement made perfect sense. Apart from defusing and de-escalating the tension, it was also an exercise in perception management, aimed at the Chinese audience, to distance Malaysia from an uninvited U.S. naval deployment, lest that Malaysia was seen as having decided to join up with the US’s confrontational stance against China. It did not want to make the “standoff” into a bigger situation than what it actually was. Moreover, if Malaysia were not careful, it could walk right into a “fait accompli” making of a deeper defense partnership that the US naval deployment could have created but which the Malaysian civilian leadership was not ready to embrace.

However, Malaysia’s strategic dilemma is not going away. It wishes to manage the South China Sea dispute with China with a credible deterrence (in which the US could help), but does not want to be drawn into the strategic rivalry between the US and China. China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea will generate more constituencies in Malaysia advocating for a stronger defense partnership or even quasi-alliance with the US, but the US’s overall determination to wage a New Cold War with China will also continue to make Malaysian leaders more hesitant than ever to embrace such a partnership or alliance. Managing such a delicate balance is increasingly more difficult, which is also complicated by the rising public scrutiny in the age of social media, coupled with nationalist sentiments. Malaysia’s effort to manage this balance and dilemma should be understood, and not pushed around, ostracized, exploited and manipulated by others for their own advantages.