Since December 2025, the US has boarded and seized 7 tankers involved in Venezuelan oil transportation and trade within “international waters” of the Caribbean Sea and North Atlantic. This series of seizures should be viewed as an extension of the maritime blockade against Venezuela initiated by the US in December 2025, albeit with a broader scope and involving more nations. Among the 7 seized tankers, some were owned by US-sanctioned entities, others had transported crude oil to countries such as Russia and Iran, and several even had connections to China. The legal basis cited by the US for this series of seizures combines domestic and international law, encompassing unilateral sanctions alongside counter-narcotics and counter-terrorism measures. Understanding this “hybrid lawfare” initiated by the US in the Caribbean is key to comprehending the US maritime strategy.

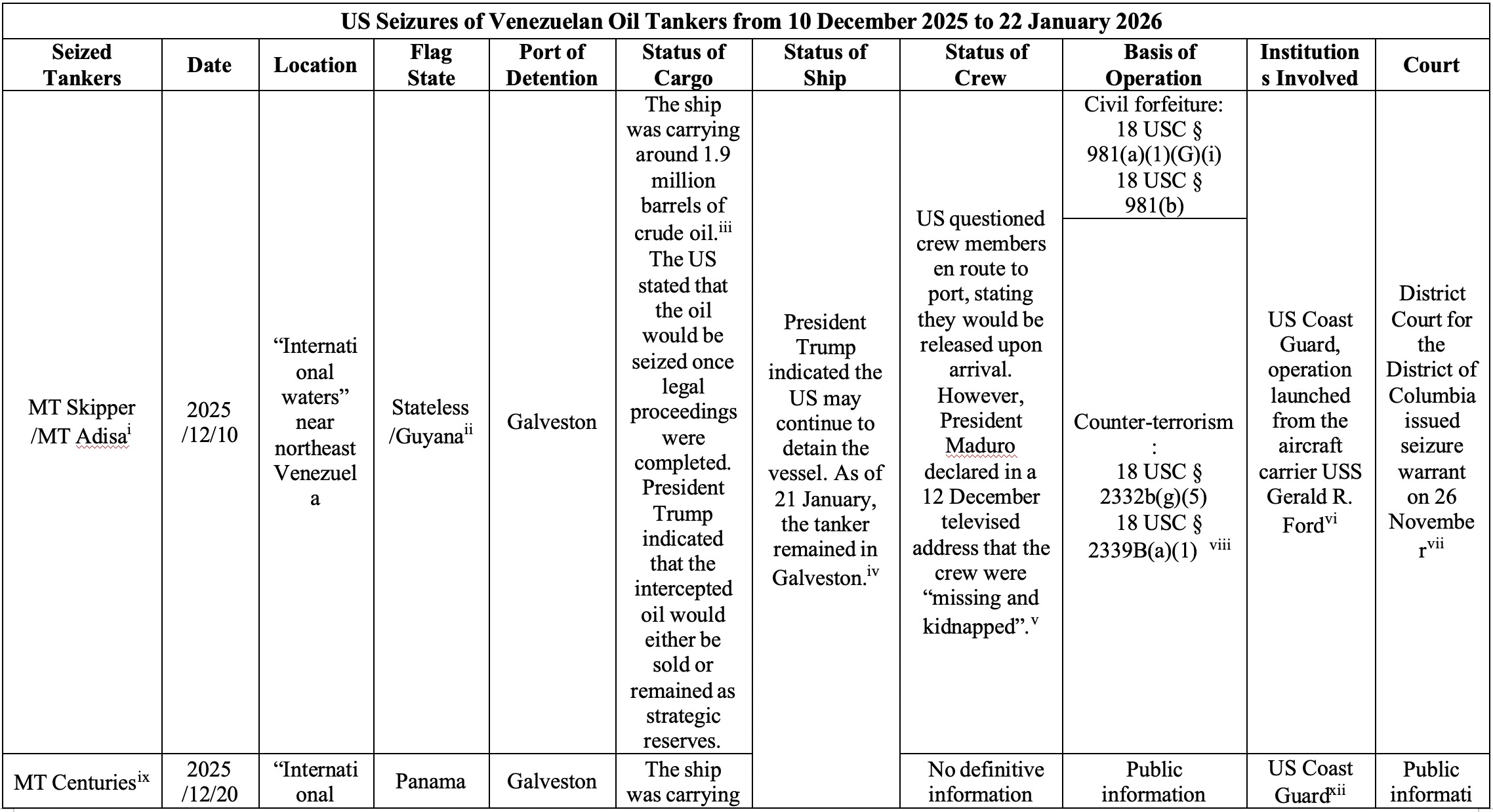

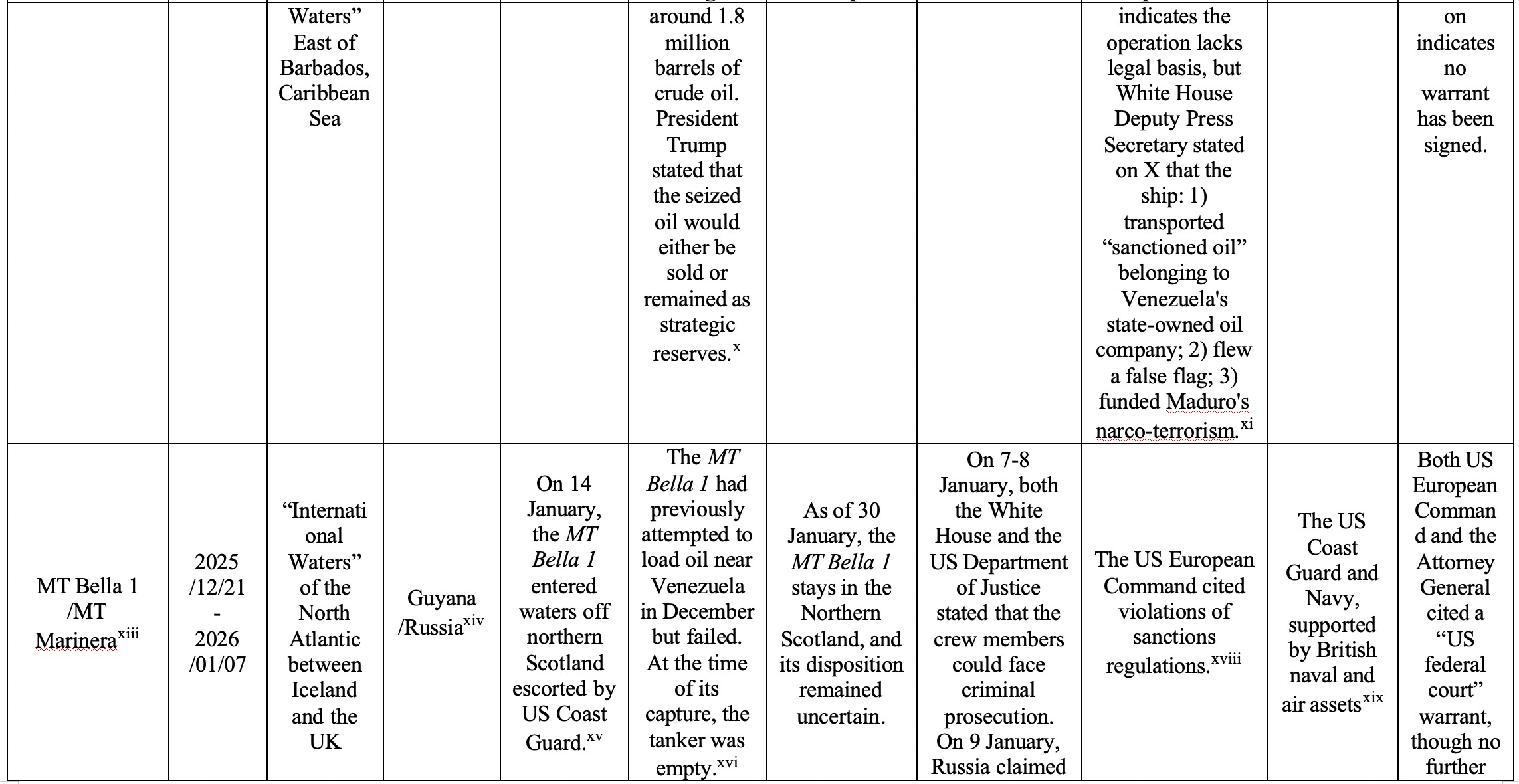

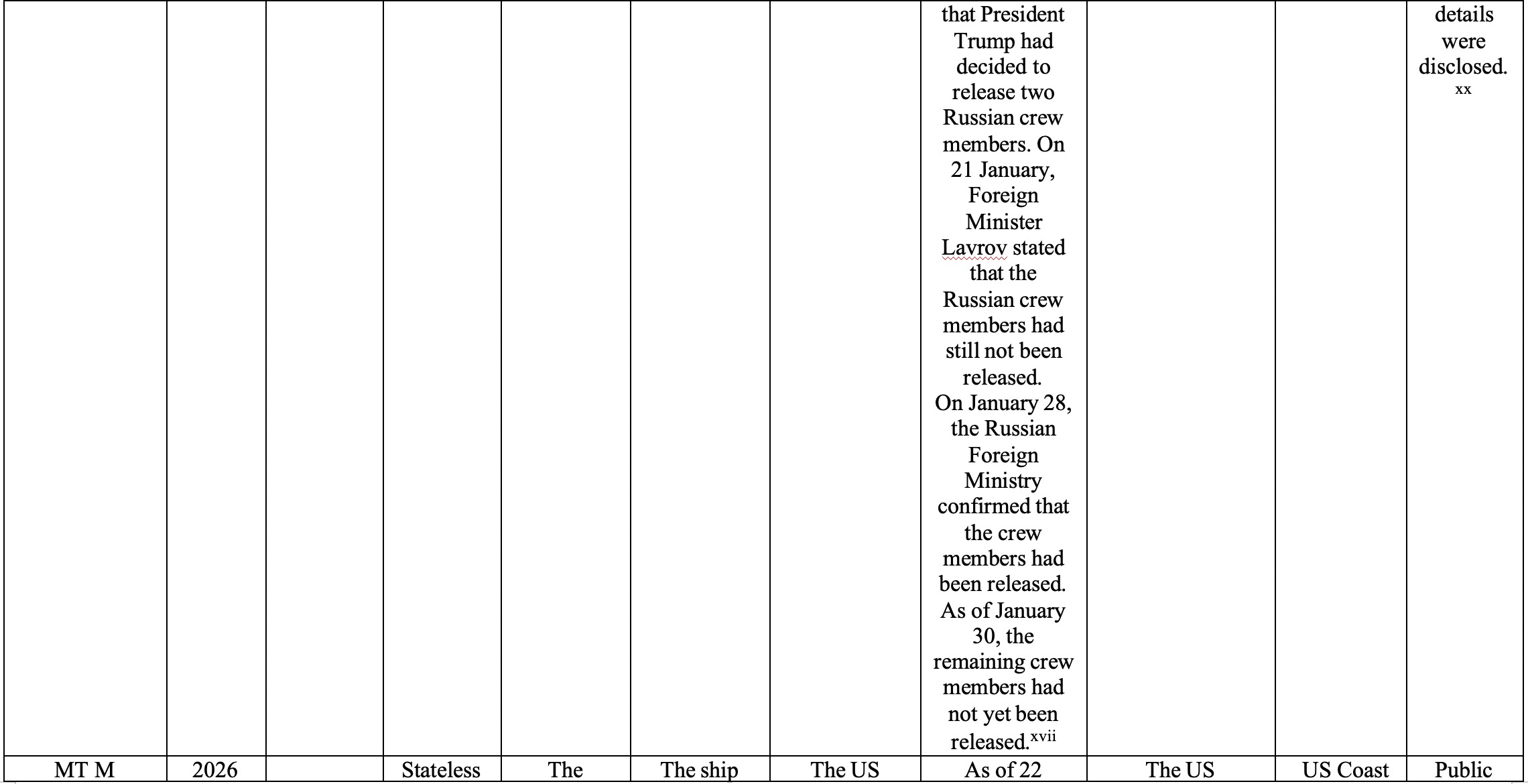

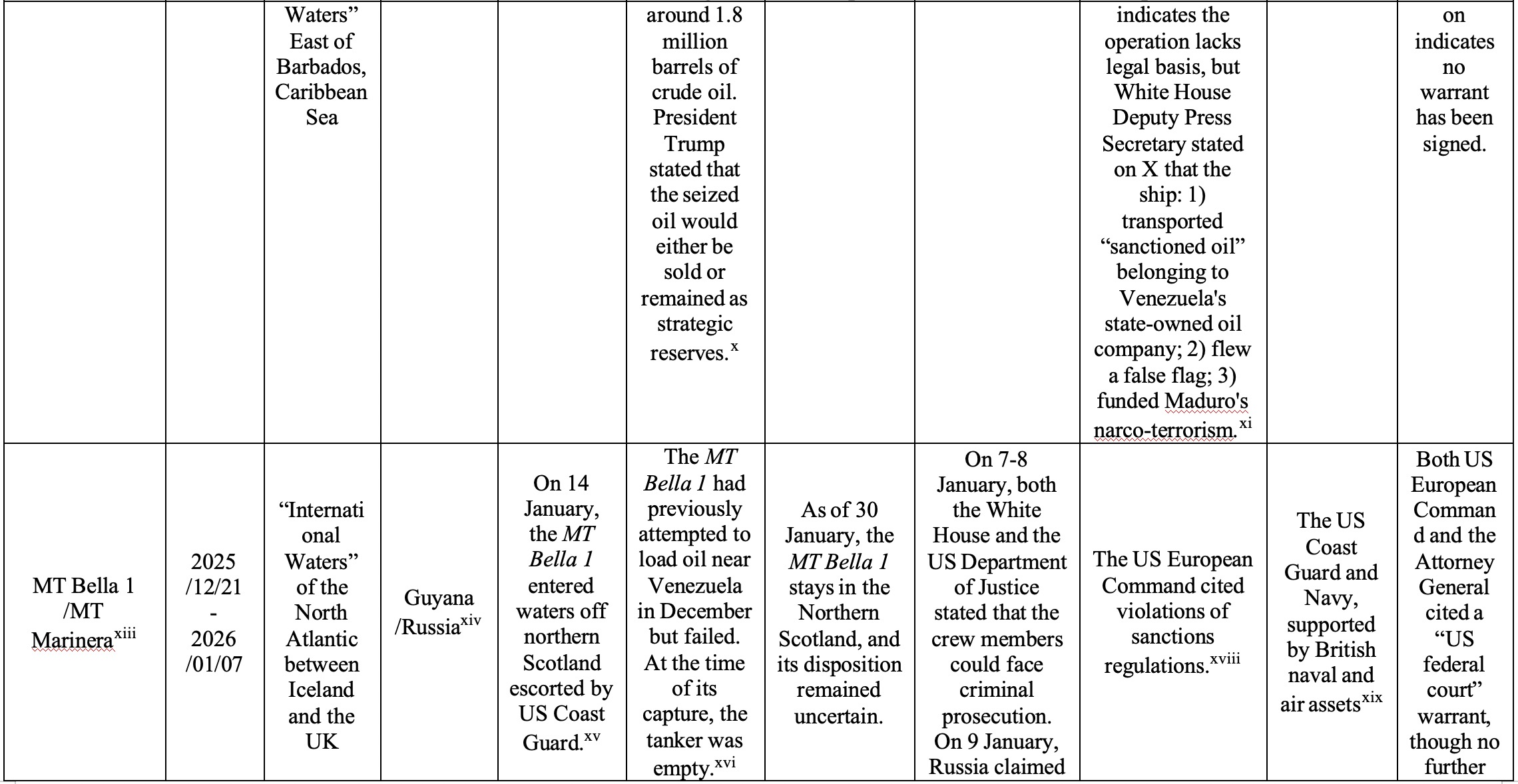

I. 7 Seizures of Oil Tankers by the US Coast Guard and Navy

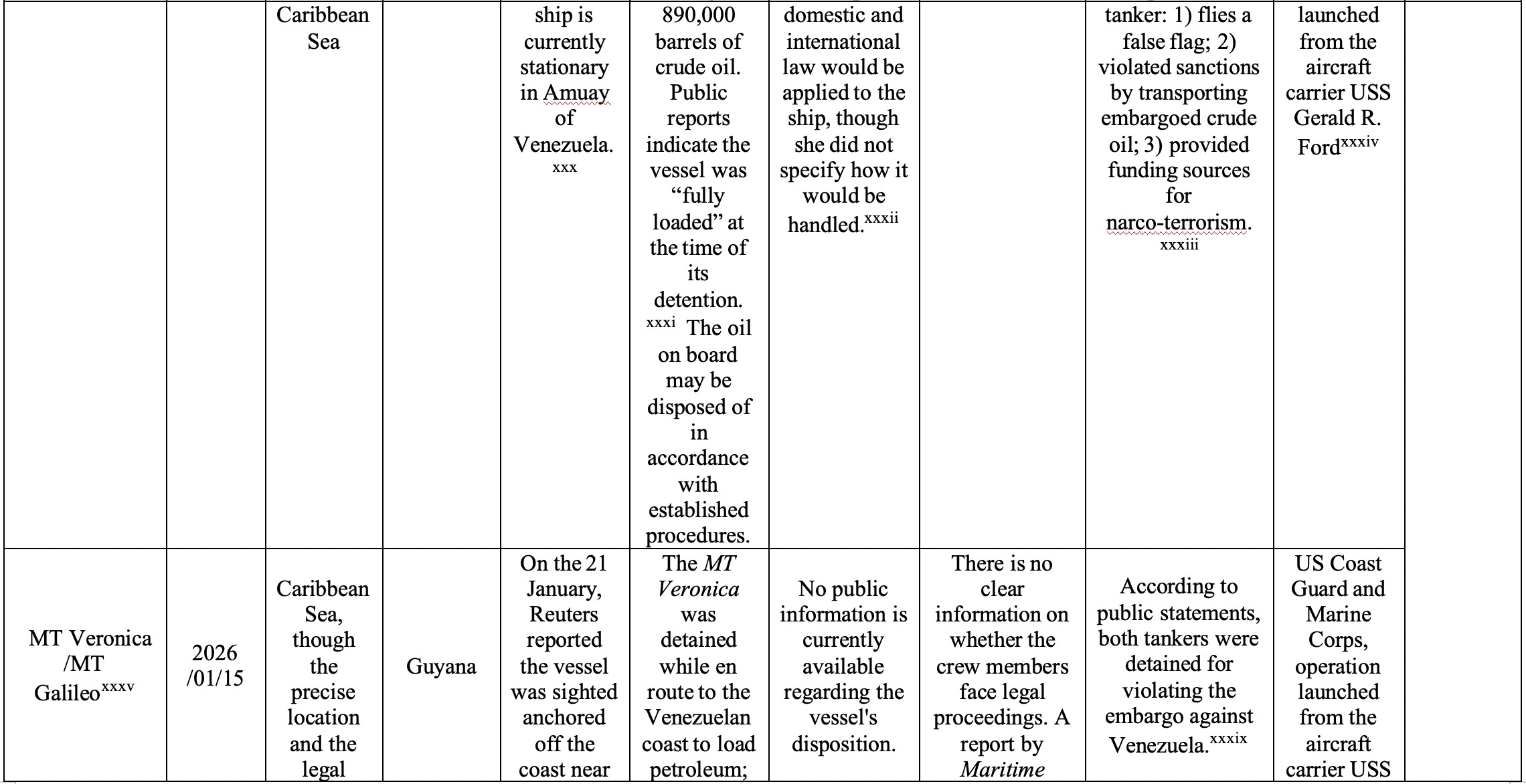

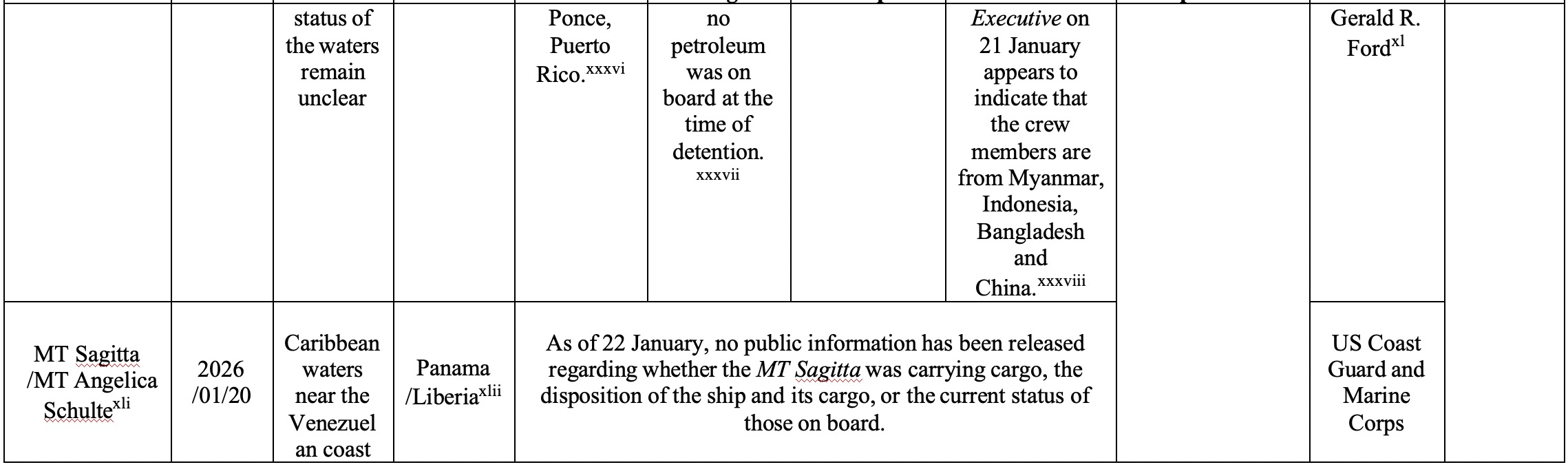

On 10 December 2025, the US Coast Guard Maritime Safety and Response Team boarded and seized the Guyana-flagged tanker MT Skipper in “international waters” near Venezuela's northeast coast. The vessel was carrying approximately 1.9 million barrels of crude oil and had recently departed from a Venezuelan port.[1] This marked the commencement of US boarding and seizure operations targeting tankers linked to Venezuela. Over the subsequent month, the US Coast Guard sequentially detained non-US-flagged tankers either currently engaged in or previously involved in transporting Venezuelan oil including the MT Centuries,[2] the MT M Sophia,[3] the MT Olina,[4] and the MT Veronica[5] in the Caribbean Sea using similar methods.[6] Following a pursuit lasting nearly 20 days in “international waters” of the North Atlantic, the US Coast Guard also seized the Russian-flagged tanker MT Marinera.[7]

Figure 1. Shipping tracks of selected oil tankers, Dec.11, 2025 – Jan. 29, 2026

This marks the first instance of the US forcibly seizing a foreign-flagged tanker in “international waters”. Previously, in August 2020, the US seized 4 foreign-flagged tankers near the Strait of Hormuz pursuant to court-issued warrants for violating US sanctions against Iran, confiscating 116,000 barrels of fuel onboard.[8] However, the operation five years ago differed from the US recent practices in two key respects: firstly, the earlier operation did not involve the use of force, instead pressuring the Greek owners of the 4 tankers through sanctions threats to compel their “voluntary” surrender; secondly, the current seizure targets not only the oil cargo but extends to the tankers themselves.

The divergent approaches adopted by Trump during his two terms reveal two defining characteristics of the US tanker seizure operation this time:

First, the method of seizure prioritises coercive force over legal sanctions. Operationally, a joint task force comprising the US Coast Guard and Marine Corps, operating from the aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78) and other US naval vessels deployed in the Caribbean, pursued, boarded, and seized the oil tankers. The pursuit of the MT Bella 1 in the North Atlantic also received support from British naval and air assets.[9] As part of Operation “Southern Spear”, the intensity of force employed by the US during these vessel seizures clearly exceeded that of routine law enforcement activities. Government statements and public reports indicate that legal justification was progressively less emphasised across the 7 seizure operations. To date, operations concerning the MT Skipper and the MT Bella 1 have explicitly relied on court-signed seizure warrants as their legal basis.[10] Among these, US authorities have only disclosed the contents of the seizure warrant issued by the US District Court for the District of Columbia for the MT Skipper, though key sections remain redacted.[11] Nevertheless, this “force-first” approach does not signify abandoning legal procedures. Reuters reported on 22 January that the US has applied for further warrants concerning dozens of more tankers involved in Venezuelan oil trade, though proceedings may take months or years.[12] This indicates the current pattern forms an “emergency situation” where enforcement precedes legal procedures, with warrants supplemented after vessel seizure.

Secondly, the scope of seizure has expanded from crude oil aboard to the vessels themselves. Following the detention of two tankers last December, President Trump stated in an interview that the US would not only retain the crude oil but also “keep the ships”.[13] Furthermore, after seizing the MT M Sophia, the US Southern Command issued a statement declaring it would escort the tanker to the US for “final disposition”.[14] Moreover, both the MT Bella 1 and the MT Veronica were empty ships without oil cargoes at the time of seizure. By contrast, in two previous seizure operations in 2020 and 2022, the US merely required the ships to dock for unloading after gaining its control, without taking further action against the ships themselves.[15] In light of this, the US' “new ship-seizure policy” is increasingly targeting ships themselves as enforcement subjects, aiming to exert greater deterrence upon the owners of so-called “shadow fleet”. Concurrently, there exists the possibility of further expanding enforcement targets to include personnel aboard the ships. Presently, crew members of seized oil tankers may face the risk of multiple criminal proceedings. Following the seizure of the MT Bella 1, White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt stated that crew members would face criminal charges due to the ship’s stateless status.[16] Attorney General Pam Bondi further indicated that crew members could be prosecuted for failing to comply with orders.[17] Although the US pledged to release all or some of the crew members following the seizure of the MT Skipper and the MT Bella 1,[18] current information indicates these commitments have not yet been fully honoured.[19]

Notably, some tankers seized by US authorities during this operation also have connections to China. The MT Centuries was reportedly transporting Venezuelan oil to a “well-known oil trader” headquartered in China when seized, having repeatedly transited the China-Venezuela oil shipping route;[20] the MT Olina and the MT Sagitta are owned by Hong Kong-based Tantye Peur Limited and Sunne Co. Limited respectively;[21] the MT Veronica is suspected to have carried Chinese crew members, though it remains unclear whether they have been released.[22]

II. The “Hybrid Lawfare” Behind the Abuse of Force

From a legal perspective, this series of seizures by the US employs a “hybrid lawfare”. Specifically, its hybrid nature manifests in two key aspects:

First, the US mixes international and domestic legal basis to legitimise its seizure operations. Despite President Trump's assertion that he “does not need international law” following the “arrest” of President Maduro,[23] the legitimacy of these operations remains largely grounded in international law. In fact, the US established its operation on the basis of the UNCLOS and bilateral agreements, among others. Some, for example, contends that owing to bilateral arrangements signed with Panama which is frequently employed in counter-narcotics operations, Panama typically consents a priori to the boarding and seizure actions against Panamanian-flagged tankers. Operations against non-Panamanian vessels, meanwhile, are grounded in the UNCLOS authorizing warships to inspect vessels on the high seas for flag state registration,[24] and to enforce US law against stateless ships.[25]

At these series of events, the MT Centuries, the MT M Sophia and the MT Sagitta either previously flew or were still flying the Panamanian flag at the time of their seizure. However, application of the bilateral boarding arrangements between the US and Panama differs from each cases. First, Panamanian authorities stated on 8 January following the seizure of the MT M Sophia, confirming the ship’s Panamanian registration had been cancelled on 23 January 2025.[26] In other words, at the time of seizure, the MT M Sophia was either stateless or registered under another flag, but certainly no longer Panamanian. Consequently, the bilateral agreement between the US and Panama should not apply, and Panama lacks the authority to grant the US jurisdiction over the ship. In this scenario, the US actions against the MT M Sophia are governed solely by the right to visit enjoyed by warships on the high seas in respect of stateless ships under international law. Second, while Panamanian authorities asserted that the MT Centuries violated the country's maritime regulations, they did not revoke its nationality.[27] White House Deputy Press Secretary Anna Kelly, however, characterised the vessel as flying a “false flag”.[28] Based on this allegation of ‘false nationality’, the US may either deny the ship’s valid registration in Panama or question the authenticity of its Panamanian nationality. Consequently, the legal basis for its operation cannot rest upon authorisation from Panama, as the latter was considered as an “incompetent” flag state, but must again rely on the right to visit. Third, the nationality of the MT Sagitta remains ambiguous. The authoritative maritime database Equasis records its nationality as “Panama False”, while neither Panama nor the US has addressed any comments on its nationality. Since it lacks further information on its status of nationality, the application of the bilateral boarding arragement in its case remains unclear, which results in the undetermined legal basis of its operation. In short, justification of the US seizure operation based on the US-Panama bilateral boarding arrangement is not tenable, and the only international legal basis on which the US could rely upon remains to be the right to visit on the high seas. Nonetheless. the crux lies in the fact that the right to visit typically permits warships only to board, inspect, and search a stateless vessel, and does not entitles enforcement measures such as the seizure of cargo or the vessel itself.[29]

To bridge the jurisdictional gap, the US has turned to its domestic law. The US District Court for the District of Columbia, in its warrant for the MT Skipper, noted that the legal basis for the operation involved provisions concerning “civil forfeiture” and “counter-terrorism” within the United States Code. As for the substantive law, 18 U.S.C. §2332 regulates “acts of terrorism transcending national boundaries”. Its subsection (b)(g)(5) defines “federal terrorist offences” to include acts of “providing material support to a terrorist organisation” as covered by section 2339(B) of the same statute;[30] 18 U.S.C. §2339(B)(a)(1) specifies that providing material support or resources to a terrorist organisation designated by the U.S. Department of State under the Immigration and Nationality Act and the Foreign Relations Authorization Act constitutes a “federal terrorist crime”.[31] The so-called “Cartel de los Soles” led by Maduro was designated as a “Foreign Terrorist Organisation” under the Immigration and Nationality Act on 24 November 2025.[32] As for the Procedural Law, 18 U.S.C. §981(a) delineates the scope of property subject to civil forfeiture, with subsection (g)(i) permitting the US to seize all domestic and foreign assets belonging to individuals or entities involved in the planning or execution of federal terrorist offences.[33] Subsection (b) further details the procedural rules governing the civil forfeiture: seizure operations shall, in principle, be conducted pursuant to a court-signed warrant, with exceptions permitting action without a warrant in circumstances including: 1) where forfeiture proceedings have been instituted in district court and the court has issued a warrant in rem pursuant to the Supplemental Rules for Admiralty and Maritime Claims; 2) where there are reasonable grounds to believe the property is liable to forfeiture and the seizure arises from a lawful procedure.[34] The domestic legal basis asserted in the warrant is the rules against narco-terrorism, the application of which is independent of the vessel’s nationality. Moreover, this legislation does not authorise the detention or prosecution of persons on board. Where the vessel is not stateless, the exercise of jurisdiction over the vessel and persons on board requires authorisation from the flag state. Where the vessel is stateless, both US domestic judicial practice and the Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations, representing the US maritime law enforcement practices, indicate that the US may take necessary action against the vessel and prosecute crew members even where the conduct of the stateless vessel on the high seas lacks any connection to it.[35] This perspective reflects the prevailing view in the US that states possess universal jurisdiction over stateless vessels on the high seas and may exercise enforcement jurisdiction.

Second, the US combines unilateral sanctions with counter-terrorism and anti-narcotics regulations to broaden the domestic legal basis for extraterritorial enforcement. Regarding unilateral sanctions, the grounds asserted by the US fall into two categories: firstly, the unilateral sanctions imposed by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) on oil tankers relevant to Iran and Russia; secondly, the blockade against Venezuela announced by President Trump last December. Apart from the MT Centuries, the remaining 6 ships have all been placed on the OFAC sanctions list. The MT Skipper was sanctioned under Executive Order 13224.[36] The other 6 tankers were sanctioned due to their connections with Russia.[37] It should be noted that the OFAC typically freezes sanctioned foreign assets but does not automatically permit authorities to seize or confiscate them. Consequently, the seizure of tankers and cargo may require additional grounds for enforcement, such as violations of the blockade against Venezuela or other executive orders.As the US unilateral sanctions are not authorised by the UN Security Council under the UN Charter,[38] the US authorities characterized the operations as combating so-called “narco-terrorism” in order to provide extraterritorial applicability for its unilateral sanctions: on the one hand, law enforcement actions against terrorism and drug trafficking on the high seas could potentially trigger universal jurisdiction;on the other hand, as noted above, US domestic law permits the confiscation of overseas assets financing terrorist entities.

III. Threats to the Rule of Law in Global Maritime Order

The US practice of seizing vessels in the Caribbean and North Atlantic follows a three-stage pattern: first, it denies the validity or authenticity of the ship’s nationality, designating it as “stateless”. Second, the US Coast Guard and Navy board the so-called “stateless ship” pursuant to the right to visit on the high seas granted by the UNCLOS. Finally, after boarding the ships, it circumvents the authorization of the flag state claimed by the ship and exercises enforcement jurisdiction under US domestic law. This action is predicated on defining the Maduro’s regime as “narco-terrorism,” thereby rendering any tanker transporting Venezuelan oil complicit in financing and aiding drug trafficking and terrorist organisations.

This modus operandi raises several concerns. Firstly, defining the transport of Venezuelan oil as “aiding drug trafficking” or “providing support to terrorist organisations” forms the core of legal justification for the US operation. Yet such allegations appear to be nothing more than a fabrication. Information indicates that neither the US Coast Guard nor Navy discovered any illicit materials aboard the seized tankers. The sole connection to narco-terrorism stems from the US unilateral designation of the Maduro’s regime as a “narco-terrorism” entity. Secondly, the US exhibits bias in its assessment of a ship’s nationality status. To confer international legal legitimacy upon its seizure operations, the US has in certain instances claimed targeted ships to be stateless on the grounds that their flag state registration lacks authenticity. The ITLOS, in its judgments concerning the M/V “Virginia G” and M/V “Saiga”, has consistently held that while the UNCLOS requires a “genuine link” between the flag state and the ship,[39] this should not be interpreted as a precondition for the flag state to exercise its protective rights, nor should it serve as grounds for other states to refuse to recognise the ship’s right to fly that flag.[40] In other words, judicial practice under the law of the sea generally holds that the “genuine link” should be understood as an obligation incumbent upon the flag state. Should this obligation not be properly fulfilled, other states may, in accordance with the UNCLOS, request the flag State to fulfil it,[41] but may not deny the flag state’s right to protect its own vessels. Finally, the US practice of enforcing domestic law in the “international waters” and exercising enforcement jurisdiction over so-called “stateless” oil tankers runs counter to international law. Legal opion holds that even if a vessel is stateless, it should not be treated as piracy thereby permitting universal jurisdiction over it on the high seas.[42] The Tribunal further stated in its judgment in the case concerning M/V “Saiga” that, except in the contiguous zone and in respect of artificial islands, installations and structures established in the exclusive economic zone in accordance with Article 60(2) of the UNCLOS, coastal states have no right to enforce their customs laws in other areas of the exclusive economic zone.[43] The implication is that, barring authorisation under the UNCLOS, states generally may not enforce their domestic laws beyond their national jurisdiction. The US enforcement of its sanctions and laws in the Caribbean and North Atlantic clearly lacks support under international law.

Moreover, threatening crew members aboard seized ships with criminal proceedings raises issues of diplomatic protection. The Draft Articles on Diplomatic Protection, formulated by the International Law Commission and reflecting customary international law, stipulate that the right of a crew member’s national state to provide diplomatic protection is not impeded by the flag state’s exclusive jurisdiction over the vessel.[44] In the case of a stateless ship, even though the ship itself enjoys no protection from any state, its stateless status does not preclude the crew members' state of nationality from exercising its right to protect them.

The serial seizures of Venezuelan tankers in the Caribbean should not be viewed in isolation. They reflect a growing tendency among certain nations to interpret the international legal rights of warships on the high seas expansively, thereby narrowing the scope of “freedom of the high seas”.The so-called Operation “Southern Spear” encompasses not only the seizure of oil tankers but also the targeting of alleged drug traffickers. The latter involves more aggressive uses of force, resulting in the killing of multiple individuals in “international waters” without identification or trial.[45] Furthermore, instances of US warships boarding foreign ships in “international waters” and arbitrarily handling cargo have become increasingly common.[46] The actions employed in these practices either operate within the “grey zones” of international law or are conducted in complete violation of it, collectively posing a grave challenge to the rule of law across the ocean shared by all. When Great Powers transform “international waters” into their own “execution grounds” through force, threats of violence affect far more than any single state; they erode the collective interests of the international society.

注:

i The MT Skipper was formerly known as the MT Adisa, registered under Triton Navigation Corp. in the Marshall Islands but managed by Nigeria's Thomarose Global Ventures Ltd. It is suspected of being a member of a shadow fleet involved in Iranian oil smuggling and sanctions evasion. See: What we know about The Skipper, the oil tanker seized by the U.S. near Venezuela, <https://www.cbsnews.com/news/what-we-know-oil-tanker-the-skipper-seized-..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

ii The ship was previously registered under the flag of Guyana; however, Guyana stated that the vessel was not registered within its jurisdiction and notified the International Maritime Organisation that the vessel had been removed from the register. See: Oil tanker seized by US near Venezuela was falsely flying Guyana flag, government says, <https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/oil-tanker-seized-by-us-near-vene..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

iii Supertanker Skipper seized by US near Venezuela is heading to Houston, sources say, <https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/supertanker-skipper-seized-by-us..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

iv In an interview on 23 December, President Trump stated that the US ‘will also keep the ships’. At that time, both the MT Skipper and the MT Centuries had been seized and were detained in waters near Galveston, Texas. See: Trump says US will keep or sell oil seized from Venezuela, <https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c87lnn09yj8o>, last accessed 30 January 2026; US pursuing third oil tanker near Venezuela, officials say, <https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/us-intercepts-another-vessel-near..., last accessed 30 January 2026; Marine Traffic, <https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/details/ships/shipid:211433/mmsi:37..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

v Estados Unidos prevé liberar a la tripulación del buque petrolero incautado cerca de Venezuela, <https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/mundo/estados-unidos-preve-liberar-a-la-t..., last accessed 25 January 2026; Venezuela denounces Trump's order for ship blockade as 'warmongering threats', <https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c4gej5ezyypo>, last accessed 25 January 2026.

vi Marines, Coast Guard Seize Tanker Olina in Caribbean, <https://news.usni.org/2026/01/09/marines-coast-guard-seize-tanker-olina-..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

vii U.S. Unseals Warrant for Tanker Seized by Coast Guard Off the Coast of Venezuela, <https://www.justice.gov/usao-dc/pr/us-unseals-warrant-tanker-seized-coas..., last accessed 25 January 2026

viii In the warrant issued by the District Court of the District of Columbia, the section concerning the MT Skipper's involvement in or facilitation of terrorist activities has been redacted and withheld from disclosure. See: IN THE MATTER OF THE SEIZURE OF THE M/T SKIPPER WITH INTERNATIONAL MARITIME ORGANIZATION NUMBER 9304667, <https://www.dcd.uscourts.gov/sites/dcd/files/25sz50.pdf>, last accessed 30 January 2026.

ix The MT Centuries was alleged to have been transporting Venezuelan crude oil to a ‘well-known oil trader’ headquartered in China at the time of its seizure, having previously made multiple voyages between Venezuela and China. See: China says US seizure of ships 'serious violation' of international law, <https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-says-us-seizure-ships-serious-..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

x In the absence of warrants, it remains unclear whether the cargo on board has been seized and confiscated or unloaded from the ship. Currently, the only publicly available information is President Trump's general remarks during a 23 December interview regarding how the US would handle the oil transported by the vessel in question.

xi Exclusive: US intercepts oil tanker off Venezuelan coast, officials say, <https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/us-interdicting-sanctioned-vessel..., last accessed 29 January 2026.

xii U.S. Coast Guard Pursues Oil Tanker Linked to Venezuela, <https://www.nytimes.com/2025/12/21/us/politics/us-coast-guard-venezuela-..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xiii The MT Bella 1 was previously associated with Turkey-based Louis Marine shipping company, though reports indicate the vessel is now controlled by Burevestmarin, a Russian company owned by Crimean businessman Ilya Bugay. The ship was placed on a sanctions list in 2024 due to its links to Hezbollah, on the grounds of association with a ‘foreign terrorist organisation’. See: Crew paints Russian flag on Iran-linked tanker pursued by US, <https://www.euronews.com/2025/12/31/crew-paints-russian-flag-on-iran-lin..., last accessed 30 January 2026; see also: Owner of seized Russian oil tanker revealed to be entrepreneur from annexed Crimea, <https://novayagazeta.eu/articles/2026/01/08/owner-of-seized-russian-oil-..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xiv The ship flew the Guyanese flag in December last year, but changed its name to MT Marinera and painted the Russian flag on its hull while evading pursuit by the US Coast Guard in January this year. Russia claims the ship possessed a certificate of navigation authorising it to fly the Russian flag as early as December 2025. See: US forces attempt to board oil tanker after pursuit across Atlantic, <https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c7v0deypjl4o>, last accessed 30 January 2026; see also: Минтранс России подтвердил задержание судна «Маринэра» ВМС США, <https://www.forbes.ru/society/553297-mintrans-rossii-podtverdil-zaderzan..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xv On the 28th, a report by Marine Executive confirmed the ship was still in the Scottish waters.See: Russian Crewmembers Released from Seized Tanker Held in Scotland, <https://maritime-executive.com/article/russian-crewmembers-released-from..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xvi US says it is intercepting third Venezuelan oil tanker amid simmering tensions, <https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-12-22/us-intercepting-third-venezuelan-..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xvii US seizes Russian-flagged tanker in Atlantic as UK confirms it gave support to operation, <https://www.bbc.com/news/live/cwynjdqgellt>, last accessed 30 January 2026; Attorney General Pamela Bondi, <https://x.com/AGPamBondi/status/2008965337157451806>, last accessed 30 January 2026; Moscow says US freed two Russian crew members from seized oil tanker at its request, <https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/moscow-says-us-freed-two-russian-..., last accessed 30 January 2026; Russian Crew Members of Seized Oil Tanker Still in U.S. Custody, Lavrov Says, <https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2026/01/20/russian-crew-members-of-seized..., last accessed 30 January 2026; Russian Crewmembers Released from Seized Tanker Held in Scotland, <https://maritime-executive.com/article/russian-crewmembers-released-from..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xviii U.S. European Command, <https://x.com/US_EUCOM/status/2008897287691399504>, last accessed 30 January 2026.

xix UK provides support to U.S. seizure of Bella 1 accused of shadow fleet activities and Iran sanctions breaches, <https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-provides-support-to-us-seizure-of-..., last accessed 30 Janurary 2026.

xx U.S. European Command, <https://x.com/US_EUCOM/status/2008897287691399504>, last accessed 30 January 2026; Attorney General Pamela Bondi, <https://x.com/AGPamBondi/status/2008965337157451806>, last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxi The MT M Sophia has been implicated in the transportation of Iranian oil. Satellite imagery reveals that the Guyana-flagged MT Puyang loaded 1.9 million barrels of Iranian crude oil at Kharg Island, Iran. Following several transhipments, the cargo was received by the MT M Sophia on 1 May 2025. See: Inside the Ghost Armada Oil Trade that Led to the Seizure of M SOPHIA and OLINA, <https://www.unitedagainstnucleariran.com/blog/inside-ghost-armada-oil-tr..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxii Both Marine Traffic and Reuters reported that the ship’s flag state was Panama, but the US SOUTHCOM stated that the ship was ‘stateless’. The Panama Maritime Authority issued a statement on 8 January confirming that it had withdrawn the flag of the MT M Sophia in January 2025. See: US seizes Venezuela-linked, Russian-flagged oil tanker after weeks-long pursuit, <https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-seizing-venezuela-linked-oil-..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxiii After vanishing from view, two US-seized Venezuela oil tankers reappear near Puerto Rico, <https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/after-vanishing-view-two-us-seize..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxiv Venezuela Updates: U.S. Forces Seize Two Tankers; Rubio Lays Out Plan for American Control, <https://www.nytimes.com/live/2026/01/07/world/venezuela-us-trump>, last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxv “US seizes Venezuela-linked, Russian-flagged oil tanker after weeks-long pursuit, <https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-seizing-venezuela-linked-oil-..., last accessed 30 January 2026; US handing over seized tanker to Venezuela, officials say, <https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/us-handing-over-seized-tanker-ven..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxvi U.S. Southern Command, <https://x.com/Southcom/status/2008905619424620879>, last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxvii Reuters sources stated on 22 January that the US government has applied for warrants targeting dozens of more tankers involved in Venezuelan oil trade, though the process is expected to take months or years. See: US files for warrants to seize dozens more Venezuela-linked oil tankers, sources say, <https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/us-files-warrants-seize-dozens-m..., last accessed 25 January 2026.

xxviii The MT Olina was previously named the MT Minerva and is owned by Hong Kong-based Tantye Peur Limited. The ship is also linked to Sunne Co Ltd, a Hong Kong-based company with Russian connections. This entity is subject to sanctions imposed by the Biden administration. See: Marines, Coast Guard Seize Tanker Olina in Caribbean, <https://news.usni.org/2026/01/09/marines-coast-guard-seize-tanker-olina-..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxix The ship was flying the flag of Timor-Leste when boarded and seized, though statements from US authorities and public reports described it as ‘stateless’. Currently, a provisional registration certificate issued to the vessel by Timorese authorities on 11 June can be located in:Provisional Registry Certificate, <https://www.timorleste-registry.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/OLINA-PRO..., last accessed 30 January 2026; the reigistration lasts for only 3 months, see: Vessel Registration Process, <https://www.timorleste-registry.org/maritime/>, last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxx AIS tracking provided by Marine Traffic see:<https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/details/ships/shipid:184037/mmsi:55..., last accessed 30 Janurary 2026.

xxxi The MT Olina has a full load capacity of 890,000 barrels of crude oil. See: US military forces seize fifth tanker in effort to control Venezuelan oil, <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/09/us-venezuela-oil-tanker-se..., last accessed 30 January 2026; the ship was fully loaded at the time of seizure, see: CNA, <https://www.facebook.com/ChannelNewsAsia/posts/the-olina-had-left-venezu..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxxii Secretary Kristi Noem, <https://x.com/Sec_Noem/status/2009628070047604976>, last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxxiii Ibid.

xxxiv Marines, Coast Guard Seize Tanker Olina in Caribbean, <https://news.usni.org/2026/01/09/marines-coast-guard-seize-tanker-olina-..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxxv The MT Veronica, formerly known as the MT Galileo, was previously registered in Russia in 2022 and belonged to a leasing subsidiary of PSB, a state-owned bank involved in Russia's defence and financial services sectors, and has consequently been subject to US government sanctions. See: U.S. Targeting Shadow Oil Fleets Using U.N. Law of the Sea Convention, Former Coast Guard JAGs Say, <https://news.usni.org/2026/01/22/u-s-targeting-shadow-oil-fleets-using-u..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxxvi After vanishing from view, two US-seized Venezuela oil tankers reappear near Puerto Rico, <https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/after-vanishing-view-two-us-seize..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxxvii U.S. Seizes MT Veronica in Caribbean, Expanding Operation Southern Spear Against Venezuela’s Shadow Fleet, <https://gcaptain.com/u-s-seizes-mt-veronica-in-caribbean-expanding-opera..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xxxviii US Coast Guard Requests Pastoral Support for Shadow Fleet Tanker’s Crew, <https://maritime-executive.com/article/us-coast-guard-requests-pastoral-..., last accessed 25 January 2026.

xxxix “MT Veronica: U.S. Southern Command, <https://x.com/Southcom/status/2011798070816612578>, last accessed 30 January 2026; MT Sagitta: U.S. Southern Command, <https://x.com/Southcom/status/2013718812424630376>, last accessed 30 January 2026.

xl U.S. Forces Seize Venezuela-linked Tanker Veronica, <https://news.usni.org/2026/01/15/u-s-forces-seize-venezuela-linked-tanke..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xli The MT Sagitta, formerly known as the MT Angelica Schulte, is owned by Sunne Co. Limited, a Hong Kong-based company sanctioned by the US for its business dealings with Russia. It is associated with the MT Olina. See: U.S. Forces Seize Sanctioned Tanker in SOUTHCOM, <https://news.usni.org/2026/01/20/u-s-forces-seize-sanctioned-tanker-in-s..., last accessed 30 January 2026.

xlii Marine Traffic indicates the ship’s flag state as Liberia, but the Office of Foreign Assets Control's sanctions list shows the vessel as Panamanian-flagged. See: Marine Traffic, <https://www.marinetraffic.com/en/ais/details/ships/shipid:7196440/mmsi:6..., last accessed 30 January 2026; OFAC, <https://sanctionssearch.ofac.treas.gov/Details.aspx?id=51710>, last accessed 30 January 2026.