On November 17, 2024, The Philippines claims that the “Archipelagic Sea Lanes Act” (the Act) [1] it enacted is intended to regulate the passage right of foreign vessels and aircraft through the designated archipelagic sea lanes, applying only within its archipelagic waters and adjacent territorial sea. A statement from the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) asserts that many provisions of the Act are inconsistent with international law and resolutions from the International Maritime Organization (IMO).[2] Although the legislation does not involve the issue of territorial sovereignty over certain islands in the South China Sea, the matter of archipelagic sea lanes should still be taken seriously, as it affects the rights of navigation and overflight guaranteed to vessels and aircraft from China and other countries by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Content of the Act

The Act consists of 28 sections, which can be systematically divided into five parts based on their subject matter. The first part, “General Provisions” (Sections 1–5), primarily focuses on policy declarations and the definition of concepts. The second part, “Designation or Replacement of Archipelagic Sea Lanes” (Sections 6–12), stipulates the proposed course of the archipelagic sea lanes and the domestic and international procedures for their designation or substitution. The third part, “Obligations of Foreign Ships and Aircraft” (Sections 13–20), outlines the duties foreign vessels and aircraft must uphold when exercising the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage. The fourth part, “Legal Responsibility” (Sections 21–24), mainly addresses the legal liabilities for foreign vessels and aircraft face for non-compliance with the Act’s obligations during passage. The fifth section, “Final Provisions” (Sections 25–28), governs the Act’s entry into force, enforcement, and its relationship with existing legislations.

Violations of the Act Against UNCLOS and Related International Practices

1.“Partial Designation of Archipelagic Sea Lanes” Does Not Meet IMO Requirements

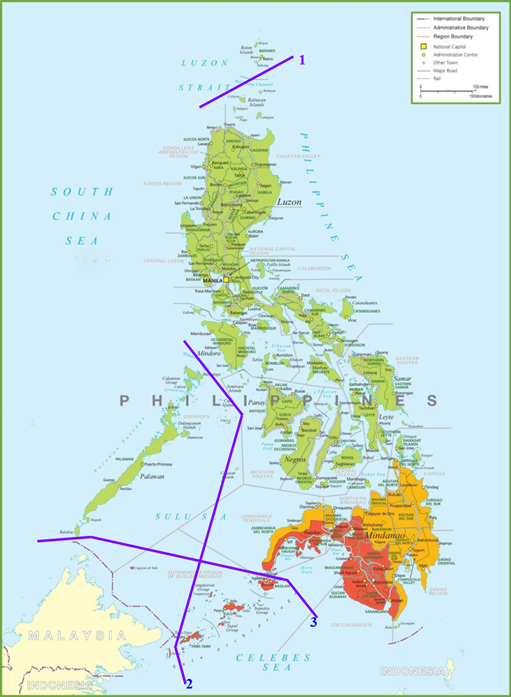

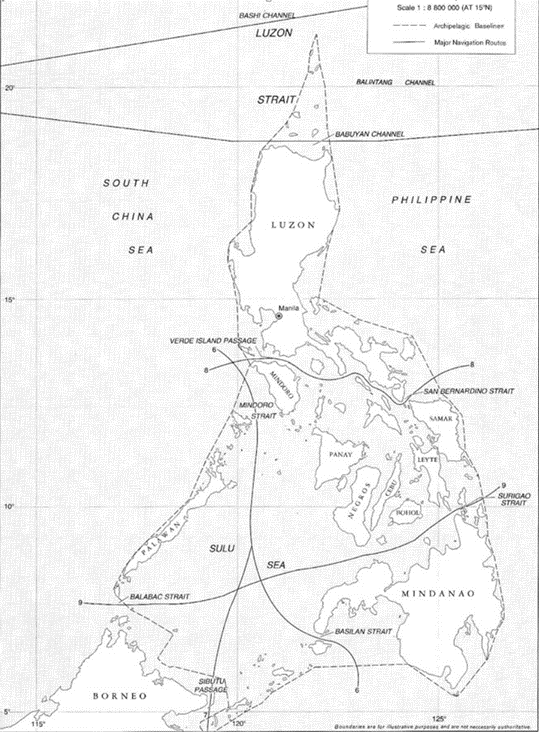

Section 7 of the Act specifies three archipelagic sea lanes proposed for designation by the Philippines (see Figure 1). However, there are more than three routes normally used for international navigation or overflight through or over the Philippine archipelagic waters (see Figure 2). [3]

A comparison reveals that the sea lanes proposed for designation by the Act are not only fewer in number than the existing normal passage routes, but more importantly, the Act does not designate the east-west lanes traversing the central Philippine archipelago (i.e., lanes 8 and 9 in Figure 2). Therefore, the Act amounts to “partial designation of archipelagic sea lanes”. Although UNCLOS does not stipulate “partial designation of archipelagic sea lanes”, the IMO created this concept for practical reasons. Even if “partial designation of archipelagic sea lanes” is permissible, two restrictive conditions imposed by the IMO must be followed: First, archipelagic states have the obligation to continue and complete the designation of the remaining archipelagic sea lanes and periodically notify the IMO of the progress of this work; second, if the “partial designation of archipelagic sea lanes” takes effect, foreign vessels and aircraft can continue to exercise their right of passage through the other normal passage routes used for international navigation or overflight in the other parts of the archipelagic waters, in accordance with UNCLOS. [4] The Act does not adhere to these two restrictive conditions: First, the Act only addresses the substitution of archipelagic sea lanes in Section 9, including no provision for adding new ones. This implies that the Philippines does not intend to complete the designation of remaining sea lanes after the initial three are designated. Second, regarding all other normal passage routes in the other parts of the archipelagic waters, Section 5 of the Act does not recognize the right of foreign vessels and aircraft to continue exercising archipelagic sea lanes passage under UNCLOS.

Figure 1: Schematic Diagram of the Three Archipelagic Sea Lanes

Figure 2: The Philippines: Major Ocean Navigation Routes

2.Granting Additional Rights to the Philippines by UNCLOS

Regarding rights not specified by UNCLOS for archipelagic sea lanes passage, the Act, which favors archipelagic states, attempts to grant the Philippines corresponding rights by analogy to the innocent passage in the territorial sea under UNCLOS. Section 15 aims to grant the Philippines the right to conduct military exercises in archipelagic sea lanes by analogy to Article 25(3). Section 19 seeks to establish the Philippines the exclusive right to set traffic separation schemes, which should be shared with international organizations, by reference to Article 22. By reference to Article 30, Section 21 aims to grant the Philippines the right to deny the passage of any foreign warships or military aircraft, if such foreign warships or military aircraft do not comply with the laws and regulations of the Philippines on passage through or over the archipelagic waters . In reality, through the establishment of archipelagic sea lanes passage rules, UNCLOS imposes significant restrictions on the sovereignty of archipelagic states over their archipelagic waters. [5] Compared to internal waters and territorial sea, the sovereignty of archipelagic states in archipelagic waters is subject to more limitations. Therefore, it is important not to automatically assume that archipelagic states have more rights over archipelagic waters than territorial sea simply because archipelagic waters are geographically located within territorial sea. It is impermissible to analogize the archipelagic sea lanes passage regime with the innocent passage regime merely because they share certain similarities. Therefore, the archipelagic sea lanes passage regime must be strictly interpreted pursuant to Articles 53-54 of UNCLOS.

3.Imposing Additional Obligations on Foreign Vessels and Aircraft Beyond UNCLOS

Going beyond the provisions of UNCLOS, Section 13(d) of the Act requires foreign vessels passing through archipelagic sea lanes may be subject to boarding and inspection by Philippine govenrment vessels when anchored due to force majeure or to assist persons, vessels or aircraft in distress. Section 13(g) imposes additional obligations on foreign vessels and aircraft, requiring them to keep their automatic identification systems (AIS), transponders, or other means of identification and communication turned on throughout their passage through Philippine archipelagic waters and shall duly respond to communications from the Philippine Coast Guard (PCG), the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines (CAAP), and other agencies of the Government of the Republic of the Philippines.. The obligations stipulated in Section 20(a) also surpass those of UNCLOS, asking foreign aircraft to comply with other conventions or treaties applicable to civil aircraft to which the Philippines is a party in addition to the Rules of the Air when exercising the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage.

4.Making “Reciprocity and Mutual Respect” a Prerequisite for Acknowledging the Right of Archipelagic Sea Lanes Passage

Section 23 of the Act stipulates that, the rights and privileges of foreign ships and aircraft in Philippine archipelagic waters herein provided are recognized under conditions of reciprocity and mutual respect. The ships and aircraft of foreign states do not abide by, or that act inconsistently with, the UNCLOS, in violation of Philippine sovereignty, sovereign rights, or jurisdiction, or resulting in injury or damage, shall not be entitled to exercise the rights, not be owed the obligations, relative to the regime of archipelagic waters and the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage under Part IV of the UNCLOS. This section is particularly misleading, requiring foreign states not to violate Philippine sovereignty, sovereign rights, or jurisdiction, or resulting in injury or damage; otherwise, their ships and aircraft are not entitled to exercise the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage. At first glance, these requirements may seem reasonable. However, regarding UNCLOS as a comprehensive agreement, it becomes apparent that Section 23 imposes additional restrictions on the exercise of the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage. In fact, reciprocity is achieved through recognizing archipelagic state status for archipelagic countries and the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage for other countries. The obligation of non-suspension of transit passage in Article 44 of UNCLOS is a general and absolute prohibition imposed on the coastal States bordering international straits, ., and according to Article 54, the obligation of Article 44 applies mutatis mutandis to archipelagic sea lanes passage. [4] Therefore, as long as the Philippines continues to assert its archipelagic state status as provided by UNCLOS, it must recognize the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage. As for the non-compliance problem, although legal responsibility must be assumed, UNCLOS separates the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage from the obligations of the flag states in exercise of the right, [7] so that the failure to comply with these obligaitions does not deny the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage.

Potential Impacts of the Act

The Philippines serves as an important transit route between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, between Northeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, and between North-East Asia and Oceania. If the Philippines implements the partial provisions of the Act that violate UNCLOS, it would have the following negative impacts on the passage of all other countries’ ships and aircraft: Firstly, it would reduce the number of archipelagic sea lanes. By only designating 3 sea lanes and refusing to designate the remaining sea lanes, as well as denying foreign ships and aircraft the exercise of the right of arhipelagic sea lanes passage through all other routes normally used for international navigation, the implementation of the Act would significantly reduce the number of archipelagic sea lanes available for foreign ships and aircraft, especially the absence of the east-west sea lanes crossing the middle of the Philippines. Secondly, it would restrict or even deny the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage. As for the designated limited archipelagic sea lanes, the Act seeks to expand Philippine control over foreign ships and aircraft, and even to completely deny the passage right of foreign ships and aircraft in the name of violating the principle of reciprocity and mutual respect. Therefore, once the Philippines starts to enforce the Act, it would inevitably impair the passage rights of all other countries’ ships and aircraft.